The Classic British Isles Buses Website

An overland trip from England to Iran in 1970

Story by Richard Gilbert.

Part One - Eastbourne to Istanbul

Last updated 4 September 2024

Email Events diary Past events list Classified adverts Classic U.K. Buses Classic Irish Buses Classic Manx Buses

-------------

Dedicated to my best mate and travelling companion Johnny Guy (RIP), who made me laugh all day long.

The day didn't really dawn. At seven o'clock it was pitch dark and drizzling gently. The household staggered into life and I had a hurried breakfast accompanied by streams of last minute thoughts from my mother. She produced a pack of food to see us through the day, including a flask of soup, a treacle tart, fruit and sandwiches ad nauseam. John drove up in the van, bang on time, shivering, cheerful and in his perpetual hurry. After all the waving and goodbyes were over, we struggled up the road, engine straining to pull our monstrously-overloaded home off on its mystery tour. Mick was waiting for us at his house and, with the three of us huddled in the cab, we set off for Dover.

It was still drizzling as we stood on the deck of the ferry and watched the vague grey outlines of Dover Harbour and the white cliffs glide into the mist.

Dover Harbour fades into the mist, 23 March 1970.

-------------

The idea of an overland journey had been gestating in my mind for nearly two years, but I felt I needed a close friend to share the experience, and nobody was available. The necessary impulse was provided finally by the co-incidence of two factors. In my case I left my airline job in an angry dispute and a mass of holiday pay. That provided me with the opportunity and the cash. At the same time my closest colleague, John Guy, completed his four-year apprenticeship as an electrician with Llewelyns, contractors of Eastbourne, and felt in dire need of a change.

When I put the idea to John one evening in October l969, he agreed immediately and the serious planning began there and then. We set our departure date as 1st January 1970 but it was several weeks before we decided even vaguely where to go. Australia was the popular choice among travellers at that time, but neither John nor I wished to go there. However it seemed an interesting direction, so we eventually decided to head that way with no real intention of arriving. There were to be two decision points en route, the half-way point Calcutta, from where we would have to cover the remaining 6,000 miles or so to Perth by sea, and the Iranian capital of Tehran, half-way to Calcutta. At both or either of these places we agreed to have a re-appraisal of our situation and decide whether to continue the journey or return. We only promised ourselves one thing, that we would definitely reach Tehran.

The next issue was the choice of vehicle. We examined all the available types and compared their properties but, since we were obviously going to be buying a cheap second-hand vehicle, we'd have to choose very carefully. The Land Rover was rejected as being expensive to buy, expensive to run, and short of space. The Ford Transit and the new Bedford vans were out of our price range, and the little CA Dormobiles were a bit small for two. In the same size-bracket were the Commer FC (now getting a bit long in the tooth, and we couldn't afford the more modern upgraded versions) and the Thames 400E, which only had three forward gears but apparently still handled hills very well. In the end we chose the Volkswagen 15cwt van for petrol economy, living space, effortless driving, air-cooled engine, an abundance of access doors, worldwide spares, quiet running and good solid construction.

Eventually we paid £40 for a 1200cc 1960 pale blue VW delivery van with side windows and 45,000 miles on the clock. It had its faults. For one thing it had no petrol gauge and, more importantly, the small engine (later models were fitted with a 1500cc engine) meant we were rather underpowered. However it did have a two-piece front windscreen with obvious breakage advantages, not that we actually ever broke one. We also paid £20 for a wreck of the same model. From this we salvaged five wheels and tyres, an engine in perfect running order, a roof-rack, spare windscreens, wipers and wiper motor, a jack, light bulbs and headlamp lenses, exhaust system, gearbox, and a complete cab door to replace a rusted one on our original vehicle. All these spares (including the door, which was swapped) we took with us and the consequent saving was immeasurable.

We both set about the conversion of the van with enthusiasm. We laid a wooden floor and covered the ceiling with polystyrene foam sheets to reduce condensation. Two single beds were built at the back of the van, one on each side with a narrow gangway between. Over the beds, suspended from the roof were two rows of cupboards, opening into the gangway. This left a space of about two feet between the top of the beds and the bottom of the cupboards. When John tried it for size he found it barely sufficient and refused to sleep on a mattress as it wasted precious vertical space. Instead he chose to sleep on the 5/8" plywood for the entire journey. He didn't complain. I found it acceptable but it was like sleeping in a closed coffin with one side missing.

At the front end of the living quarters we built a full-length wardrobe opposite the double side doors, and a sink unit and shelves. The sink was fed from a 10-gallon polyurethane water tank, an electric pump and a lot of tubing. A couple of days before we left, we decided to test it - it didn't work. The pump could only heave the water up a couple of feet, not high enough for the sink. It was too late to figure out a replacement so we thereafter let the water drain from the tank into bowls which could be used to fill the sink if necessary (at most campsites it wasn't). However the pipe did reach into the cab so, if the driver ever felt thirsty he could call out the command "Pipe!", whereupon the passenger would hand him the green hose, and he could suck until he turned blue, to be rewarded with a mouthful of warm, plastic-flavoured water with grains of sand in it. We were never aware that it did us any harm.

Meanwhile a set of elaborate crash bars appeared on the front of the van, incorporating a spare wheel attachment and wire grilles to protect the windscreen and headlamps from flying stones. With a massive tow-bar welded onto the back and a roof-rack on top, our van was now beginning to look more like an armoured car than a mobile home. This impression was accentuated by the metal panels we welded over the side windows to prevent any bandits from looking in, or breaking in. A coat of bright yellow paint came next, with a gloss white roof to reflect sunlight (even though most of it was to be covered by a tarpaulin on the roof rack). Then, with white gloss slapped over the interior woodwork, carpets and curtains followed and the construction work was more or less done.

John took the responsibility for checking the machine over mechanically and, after a few weeks, he declared it fit to go. The personality change that the poor van had undergone was amazing, and any resemblance to a delivery van was now purely co-incidental. In fact it reminded us of a long-haired cartoon dog called Dougal from the BBC TV childrens' programme Magic Roundabout, so we named it Dougal and painted the name in English and Arabic on the cab doors. In a frivolous mood one day, we decided to take a dismantled bicycle as a reserve transport device, and this we named Zebedee after one of Dougal's cartoon colleagues. John was very positive about being able to keep the van running, whatever arose. He said "You can fix anything on a car, unless it falls over a cliff." I put my trust in his optimism.

The original Dougal, from TV's Magic Roundabout.

Since we had chosen to go to Iran (also known as Persia) I decided to learn the language. It was surprising in retrospect how enthusiastically I threw myself into this exercise, acquiring various textbooks and studying it at home. The Persian language is Farsi and it has some resemblance to Arabic although the Persians would be disgusted to hear me say that. I really enjoyed the learning process and looked forward to trying it out on the natives when we got to Iran.

The British Government had a restriction on currency exchange at that time preventing all departing travellers from taking more than £50 per head out of the country. This was way below our requirement so we had to find a scheme for exporting several hundred pounds in cash. And so it was that, in November 1969, we flew to Paris for a weekend with £200 concealed in John's suitcase, depositing the funds with a trustworthy friend of mine at Beauvais Airport. Immediately after this smuggling trip the restriction was withdrawn, making the whole exercise unnecessary!

It was now obvious that we would never be ready to depart by January so we changed the target to the 1st of March. As this date drew near, work speeded up assembling the various things we intended to take. We bought boxes and boxes of tinned and packet foods from a cash-and-carry warehouse, and a petrol stove to cook on. We felt that petrol would be available everywhere whereas paraffin or gas might not. We later found that this wasn't the case and we really should have used gas. The choice of petrol was to have other unfortunate consequences too.

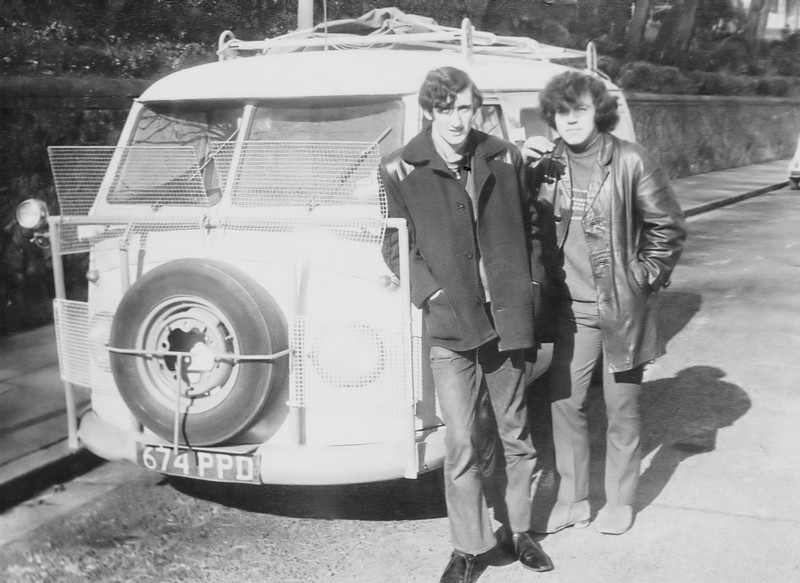

John and me, posed for a pre-departure local press photo in Tutts Barn Lane, Eastbourne. I'm starting to get a reputation for having trousers too short for my legs!

Being musically-inclined we decided to take two guitars, an amplifier, a microphone and stand, several harmonicas and a tambourine. In addition we took both mains and battery-driven tape recorders and record players. A transistor radio came too, although it packed up on the first day. John (using his newly-apprenticed electrical skills) rigged up a complex but effective 12-volt lighting system for the interior. He set up two batteries which could be switched between the engine and the lighting. So if we flattened one battery in the evening by using it for lights and music, we would start the engine next day with the other battery and then, once the van was safely on the road (and preferably at the top of a hill so that we could roll down it to get the engine started), switch them over so that the dead one could be charged up again as we drove along. It worked really well and kept both batteries topped up at all times. Meanwhile I was spending days in London visiting embassies and tourist offices collecting visas and brochures, arranging with the RAC for route guides and maps, and struggling to obtain an expensive but essential document called a Carnet de Passage.

The concept of the Carnet de Passage was that it guaranteed you wouldn't sell your vehicle illegally as you passed through a country, thereby avoiding local import tax. As you entered each country your passport, the vehicle and the Carnet became registered together, and you couldn't leave without producing all three once more. So effectively it was a passport for the vehicle, enabling it to transit a country temporarily without paying import duties. Another necessary document was the international vehicle insurance known as the Green Card. It worked in some countries and not in others - nothing was simple!

I also obtained a driving licence! In fact I had already been driving motorbikes and three-wheeler cars for some years (you could do that with a bike licence) but hadn't passed a test to drive a proper car. A clan of us had always hung around together from school days and one of them, Woody, was acknowledged to be the most experienced and knowledgeable when it came to driving matters. He had given several of us lessons and assistance over the years, so I turned to him for help. Woody told me that my driving technique learned on three-wheelers (I had owned a couple of Berkeleys) would probably see me through, but I needed practice with reversing round corners. So we took the VW van to a quiet part of Eastbourne and worked at it. It was impossible to see anything in the rear-view mirror due the huge volume of junk we were assembling in the back, so I had to rely entirely on wing-mirrors (which he said was an excellent thing to do anyway). I got the hang of it, passed the test first time (in the van) and instinctively use wing mirrors all the time to this day.

Me and John, the day before departure, 22 March 1970.

Slowly Dougal was filling up with the artifacts of overland travel, a spade for digging us out of ditches, a five-gallon army petrol jerrycan (Jerry the Can), padlocks on all doors, ropes and a tarpaulin for the roof rack, a hydraulic jack, cans of oil, distilled water, brake fluid, a tool kit and a cabinet of nuts, bolts, light bulbs, fuses and spares of every description. On the domestic side water-sterilising tablets and salt tablets joined the bulging medical kit, although we never used either of them. By mid-February we felt ready to buy the ferry ticket, and the new date set for departure was March 23rd. Now the final preparations were conducted in earnest. Kitchen and toilet utensils, piles of clothes, blankets and towels were made ready for loading, along with John's fishing rods (which we never used). Our International Driving Licences and the Carnet de Passage arrived from the RAC (who were very helpful to us in many ways) and I sent a postcard to my colleague at Beauvais Airport to say when he could expect us to call for the cash. Mick Green, another old school friend of ours, asked us if we could give him a lift to Paris as he fancied a break and thought it might ease the departure for us. We agreed.

On the last day we loaded the final things on board, filling every empty corner with more cans of beans or packets of soup. There were a few things that still needed to be done around the van but we elected to finish them off as we went along. We said that any job that was postponed in this way would be sorted out "on Montpellier beach". This sounded exotic but we didn't check whether we would actually drive through Montpellier (we didn't) or if it had a beach (it doesn't). And so it came about that we left Eastbourne at 0630 on 23 March 1970 (with 45,760 miles on Dougal's clock) and were on board the 10.30 Sealink ferry SS Lord Warden from Dover to Boulogne with the white cliffs vanishing behind us and an unknown destination ahead.

John Guy (in heartfelt prayer) and Mick Green awaiting departure of the ferry to Boulogne. 23 March 1970.

"Well men, how do you feel?" Mick asked, as though compiling a routine psychology report. To tell the truth we felt nothing at that moment, and it would be some time before the full impact of our migration would dawn upon us.

We had a beer and a long chat and I felt bit seasick as I always do, and then Boulogne appeared out of the mist and we prepared to abandon ship. We were first out and drove into the customs park. A portly gendarme strutted to the cab window and said Green Card? with an accent as thick as garlic. We produced it. He peered into the van, observed the two guitars and said "Orchestra?" We said "No" and he waved us on with no further interest.

Mick Green and me on the Lord Warden ferry to Boulogne, 23 March 1970.

John was chief driver, having far more experience than I did, of course, so it was his honour to be the first to pilot us on foreign soil. He roared away from the harbour with great confidence until another car approaching head-on reminded him that we should now be on the other side of the road. I suppose the drivers of Boulogne are used to this daftness by the Brits. All day we had to concentrate hard on our driving but by the next day we had settled down and were driving on the right quite naturally. Our first port of call was Beauvais Airport, about 70 miles inland, to collect our cash. We were very relieved to find it secure in the safe of the Chamber of Commerce office where it had waited all that time for us. We stretched our legs, bought some coffee and a couple of bottles of cheap red wine, then set off again into a grey overcast afternoon.

At about 6 o'clock it was getting dark and we were getting hungry, so we stopped in a village called Meriel and sought a suitable site to settle. We chose the forecourt of a half-built bungalow, and made our first meal with the dubious attraction of peas and instant mash in the same saucepan. After eating, and drinking the wine, we went into the village to explore but, typically at that time of night, the whole place seemed deserted save for a few belligerent guard dogs, so we gave up and called it a day.

We awoke at 7:15 and, after a clean-up and coffee, joined the N1 again bound for Paris. I suppose we reached the city at about 9 o'clock but it was nearly an hour before we could be sure. Finally we managed to get off the Route Periferique (Paris's M25) in continuous drizzle, and battled our way through the city traffic, down underpasses, up flyovers and through tunnels until we arrived at Place de la Republique somewhat shattered.

At this point Mick elected to leave us and make his own way back eventually, so we took him to the little hotel in Rue du Turenne that John and I had used on our previous visit and then, after he had checked in, went all went back to the airline terminal in Republique for a cup of coffee and farewells. We were finding Paris rather depressing and overwhelming in the rain so we decided not to delay our departure any further and, after buying a loaf of bread and saying a final goodbye to Mick, we splashed off in search of the Autoroute du Sud, leaving him standing by the Metro entrance looking as depressed as the city that he faded into.

Paris is a magnificent city with an atmosphere all of its own and John and I were aware of this but, on that cold grey wet day, the thought of Mediterranean sunshine made us eager for a swift exit. We had no trouble finding the Autoroute, and discovered it to be one of the best and fastest roads we drove on in all Europe. John had been driving in Paris as I found it too much of a challenge at that time, but I took the wheel for the Autoroute and, as I put my foot down, our spirits rose. Then we got a nasty shock; several miles down this beautiful motorway a huge barrier across the road prevented any further progress until we collected a toll ticket. This ticket was marked with the name of the entry point, and it then became impossible to leave the Autoroute without passing through a similar check-point, where a toll would be charged for the section of road used. We had never seen such a thing before! Since we were being very careful with our money, and the toll was quite high we decided to leave the Autoroute at the first available exit and take the old road which followed more or less the same route. Anyway at our modest cruising speeds it wasn't going to make much difference.

Even if this did slow our progress slightly, it made for a more interesting journey. As we drove south the map began to come to life; Auxerre, Avallon, Chalon, Macon, each town more attractive than the last, and the countryside more picturesque. In the early evening we picked up a girl hitch-hiker who was going to her home in Marseilles. We struggled with our French for a while, but all we learned was that she thought our progress was too slow and she would be better off with someone else, which wasn't very courteous of her. So we dropped her again just outside Chalon and I hope she's still standing there. At ten o'clock we stopped for a beer at a cafe near Villefranche and then parked for the night on farmland overlooking the Autoroute. We slept well, despite the smell of petrol which seemed to be leaking from our stove. We had covered 230 miles, an average day.

We were up by 8.30, but an involved breakfast meant that we didn't get on the road until nearly 10, when we drove straight into Lyons which appealed to us both. The River Rhone and the Saone met just outside the town, and both ran through the middle. The Saone was much wider than when we had seen it further north, and both rivers appeared to be nearing flood level. The Rhone ran south beside the road and, as we followed it to Valence, it became obvious that at the best of times it was a pretty big river, but now it was huge and spread over all the countryside at this apparently ominous level.

John at the wheel, south of Lyons, 25 March 1970.

The scenery was amazing, craggy slopes and perilous bends as the road wound through the Massif Centrale. The towns and villages seemed cleaner and more friendly than in northern France and, as our morale rose, we decided to try to reach the Mediterranean by nightfall. We came into Avignon in the late afternoon, had a glass of beer, watched some old men playing the French game of Boules then, after seeing one of the famous bridges, we set off again for Aix-en-Provence.

By 9 o'clock it was dark and we had to leave the main road for an incredible winding trail across the Alpes Maritime. If we had seen the road in daylight it would probably have petrified us, due to the steep cliffs and sheer drops on each side of the road. At one point we shone our mobile spotlight over the side of the road and we couldn't see the bottom of the drop. Then the filament broke and the light never worked again.

This was ideal country for James Bond or the Monte Carlo Rally. On the way down the other side of this spectacular film set we came to a remote village called Grimaud, where we saw our first palm trees and fancy villas built up the side of a hill. Illuminated by the street lamps it seemed like another world. We pressed on and half an hour later came at last to St Tropez where there were palm trees galore. Although 11 o'clock at night it was beautifully warm, and we stood in the square in our shirt sleeves in amazement. We had driven hard that day and covered 400 miles but it was worth it and, when we found a beach to park beside, we just sat on the sand under a palm tree and looked at the sea, speechless. At that moment we were able to answer the question that Mick had put to us on the boat at Dover. At last we knew how we felt; we felt we had really achieved something and had a wonderful sensation of freedom.

Dougal basking on 'Plage Tahiti', St Tropez, where we spent the night. 26 March 1970.

I awoke to find that we were moving. I poked my head through the curtains into the cab to ask what was going on. Blazing sunshine hit me as I glanced at my watch - it was half past seven. John was steering the van through a column of sun-bronzed beach people. Apparently he had been semi-nude when this crowd suddenly poured onto the beach, so he decided to drive away before somebody evicted us!

Spring-clean for Dougal at St Tropez. 26 March 1970.

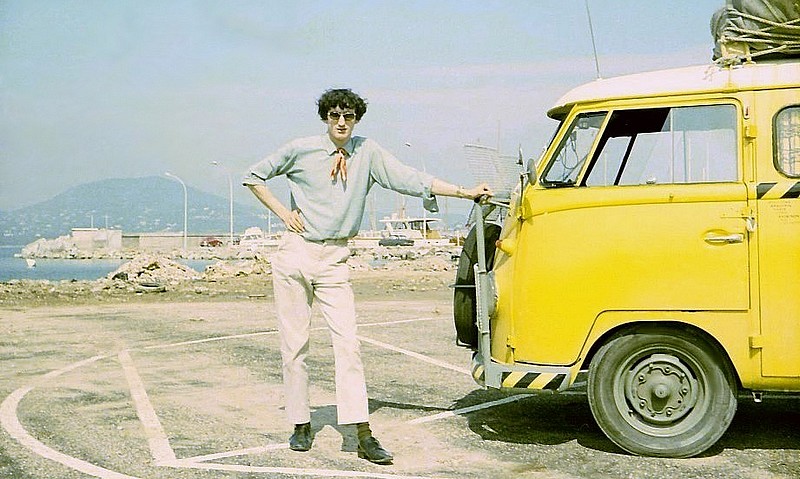

We moved to a huge empty car park at the harbour where we made a sort of breakfast and then set about a massive spring-clean (this was to be our Montpellier beach). Everything was hurled out of the van and, while John plastered all the inside walls with pictures of girls, cars and Eric Clapton, I washed the road-dust off our sparkling yellow paintwork. Then everything was neatly packed away and we stood back to admire our handiwork. Dougal was a fine looking beast and ready for anything, which was just as well because we had some difficult terrain to cover along the coast.

What a cool dude, or maybe a king prawn. Me adapting to the south of France.

We set off after lunch and followed the cliff road cut out of the red rock through St Raphael and Miramar and all the other exotic and fearfully expensive resorts with their golden beaches, yachts and casinos. Then it was back to sea level at Cannes, which was full of US Navy sailors from the enormous aircraft carrier USS Forrestal anchored outside the harbour.

The glorious sunshine faded into a warm calm evening as we approached Nice, where we stopped off at the airport. Our visits to airports were based not only on my interest in aviation but also on an element of good sense. Airports held many benefits for the overland traveller since they were public places that kept long hours, provided toilets washing and shaving facilities (often free of charge), refreshments, tourist information, English newspapers and an accurate time-check, to name just a few. We were surprised that our fellow travellers didn't take more advantage of this, but it explains why, on occasions, this journey might appear to be simply a matter of hopping from one airport to the next.

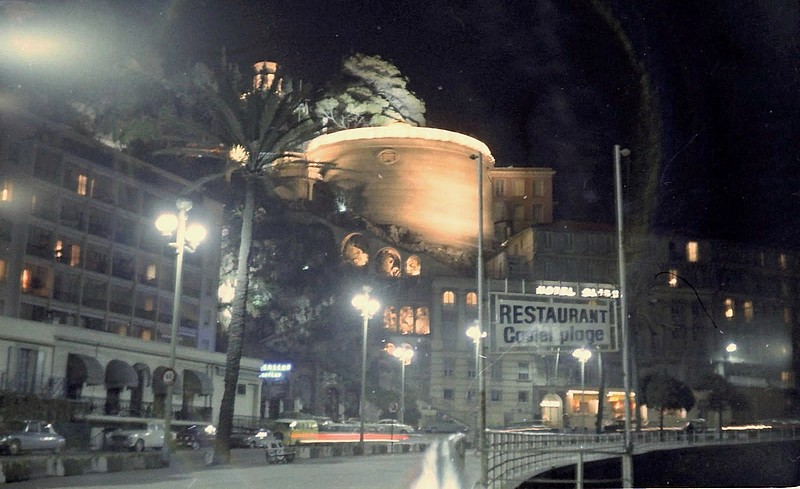

Nice seafront at night. Dougal is just visible, left of centre. 26 March 1970.

We had a look around the smart, bright terminal after a wash and brush-up, in an effort to find someone to change some money into French Francs. We eventually made a dubious transaction with a taxi-driver, then rejoined the wide dual carriageway into Nice to see the sights. As we drew up on the exotic sea front I realised that I had left my glasses back at the airport so we had to return. To my surprise and relief they were still where I left them "...which says something for French honesty," or as John phrased it in our log, "perhaps they would not fit the Gallic nose."

On the second attempt to explore we were more successful, although everything seemed so expensive that we confined ourselves to walking the streets and looking around. This time it was the turn of the Royal Navy, as aircraft carrier HMS Hermes and accompanying vessels were visiting, so there were sailors everywhere and a corresponding number of ladies of the night, obviously doing a lively trade. After being accosted by working girls a couple of times we thought it best to leave town, and decided to drive on to Monaco to spend the night.

While negotiating a steep descent on the craggy coast road into Monte Carlo, we heard an ominous regular squeak from somewhere. We stopped the engine and rolled gently down the hill to listen more closely. It had to be a wheel bearing so we got out to investigate, but the squeaking continued even when we stopped. Then we saw the cause of our concerns - a lone bat weaving through the palm trees. We drove on with some relief. Monte Carlo came into view just after midnight, just as we completed our first 1,000 miles. The town was very striking, being clean and white with many floodlit villas and houses surrounded by a galaxy of palm trees in the Cote d'Azur fashion. Descending almost to sea level we settled in a car park overlooking the shore. After trying (but failing) to receive an English radio station on our battered transistor radio, we went to sleep.

Bright sunshine and a strong cold wind brought us to life in the morning, and we immediately remembered that we had arranged to call at the Nice Poste-Restante to collect any mail from England. This gave us the opportunity to travel the road back to Nice in daylight, which proved to be a remarkable journey through tunnels, mountains and cliffs that we had not seen at all the night before. There was no mail however, so we left instructions to redirect any that arrived later to the Poste- Restante in Istanbul, and returned along the lower coast road to Monte Carlo.

The coast road from Monte Carlo back to Nice, 27 March 1970.

Prince Rainier's palace stood on the top of a promontory overlooking the harbour and city and part of it was open to the public, being attached to a maritime museum. Entry to the palace was too expensive for us so we walked around, admiring the outdoor exhibits and the view, especially from the palace yard, guarded by casual sentries in elaborate uniforms covered in gold braid and tassels. A Brazilian and then a Chinese guy asked us to photograph them with their cameras, and the fellow from China returned the favour for us; but a cold wind soon drove us back to the shelter of Dougal's cab and we left Monaco shortly before lunchtime.

The photo of us from the Palace overlooking Monte Carlo taken by the Chinese tourist, 28 March 1970.

It's only a few miles from Monte Carlo to the Italian border just beyond Menton, and we were a little apprehensive about crossing our first land frontier. However it went quite smoothly apart from some confusion over compulsory petrol coupons on the Italian side. The Italian coast contrasted starkly with the affluence of France and, despite magic names like San Remo, Alassio and Albenga, we found it all rather depressing. For one thing the weather turned miserable and the sea turned grey but, most of all, the Italians seemed incapable of maintaining the clean, bright, efficient appearance of the French resorts.

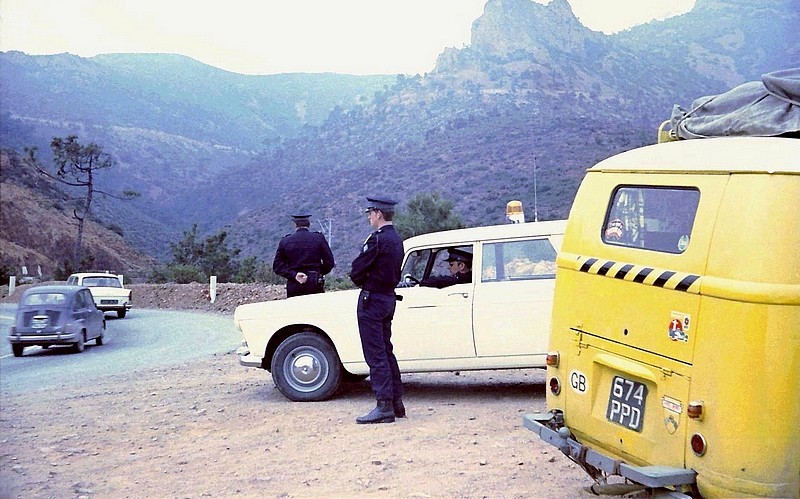

French police take a breather near Menton, close to the Italian border. 28 March 1970.

Savona boasted a massive ship-breaker's yard but little else (as far as we could see) and increasing drizzle welcomed us to Genoa airport as dusk descended over the marshalling yards, docks and industrial complexes. The airport lounge provided us with no relief from the depression outside, being a rather primitive affair with almost no facilities for our benefit, so we drove into the town centre and decided to take a look around on foot.

Having locked up the van and double-checked the padlocks, we nervously wandered out into the drizzling drabness of Genoa. John recommended carrying our knives for this excursion, a decision which surprises me in retrospect since, by the time we had reached Istanbul - surely a more dangerous city - we had given up carrying these weapons. Perhaps we became complacent as we went along, but the general impression gained was that the world was not nearly as threatening as John, in particular, had imagined. After fingering these uncomfortable devices in our pockets for a while I ventured to ask John if he knew how to use a knife if the occasion arose. He confidently replied that, if in difficulties, one pulled out the knife and began to clean one's fingernails with it, at which the assailant would retreat petrified. "And if they don't?" I asked. "Then you run like hell!" replied our brave explorer.

We parked near Voltaggio on the road to Milan that night, on an allotment between the main road and a railway bridge so low that our radio aerial suffered as we passed beneath. Next day, a late start brought us into Milan in the early afternoon. Steady rain prevented us from venturing out of the van as we drove past the magnificent cathedral, but we did visit Linate airport for the usual leg-stretch after failing to find Malpensa, Milan's primary airport.

That evening saw us in Brescia with the weather a little improved. The city centre is very attractive in places with some beautiful examples of traditional architecture. Brescia was basically industrial and appeared to have little to offer the tourist. However we felt that, while in Italy, we really ought to sample a real Italian pizza pie, and this seemed a good opportunity. The little ristorante provided us with fine examples, though John was not too sure about his and washed it down with coffee and beer. An Italian girl sitting at an adjacent table with her mother struck up a conversation with us in excellent English and we joined them for the rest of the evening, finding them most sociable. Isabella said she would bring a friend in the morning and give us a conducted tour of Brescia, to which we agreed with pleasure and, after a final drink at a little corner bar, we drove them home and settled for the night on a huge empty car park nearby.

We spent most of the morning servicing Dougal in the car park, including a messy oil change, punctuated only by the arrival of Isabella to say that her father was ill and the tour was off. We guessed that her father was probably not ill but very angry - anyway that was that. The Sunday morning occupation of the locals seemed to be driving in wide circles around the car park. Whole families sat in cars drifting idly round and round, sometimes three or four vehicles at a time, an activity that puzzled us a great deal.

After lunch we joined the SS11 road towards Venice but, after encountering heavy traffic, we decided to pay our money and take the Autostrada. Dougal immediately ran short of petrol, the lack of a petrol gauge having caught us out. By slewing back and forth across the road and pumping at our reserve petrol knob, we managed to cover five miles or so, largely down the hard shoulder, to the nearest petrol station.

Inevitably the first we saw of Venice was the airport, which was surprisingly quiet but clean. Venice itself was an extremely confusing place and we ground to a halt at the end of a causeway where we found nothing except a car park and a roundabout for going back. A stream of people seemed to be coming from somewhere on foot, and it was forbidden to take a car further, so we set off to walk into old Venice with its canals, bridges and gondolas. It was all very beautiful and did not smell as badly as we had been led to believe, but we found it very easy to get lost. To return to the van I tried navigation by the stars, but we wound up in dark back streets and would be there to this day, were it not for John's natural sense of direction.

Parked nearby was a British Bedford Dormobile with AUSTRALIA painted on it. Someone had stuck a friendly note on the windscreen saying they were on the same route and were in the muddy car park opposite. We left a similar note and went into the car park to meet the other team. Due to poor communication with the attendant we ended up with a ticket to stay all night, so we decided to do just that. Several British vans were in the park and we had a chat with some of the occupants before going to sleep.

After waking refreshed and cooking breakfast amidst the muddy puddles before the other vans came to life, we eventually greeted our fellow travellers and had some long conversations, swapping stories and gathering advice. It soon became apparent that we were as well (if not better) equipped as any of them, which was certainly encouraging. One rather ropey Dormobile contained a young party of three from Blackheath who seemed to be spending money like water. We felt that they couldn't possibly get far in such a fashion. The Bedford next to us, which we had seen on the causeway the day before, was manned by three lads, a New Zealander, a South African and an English hitch-hiker. This group appeared to be much more professional and provided us with a wealth of useful information. They were going to Istanbul, then back to London and had clearly done this kind of thing before. When we said farewell just before lunch we hoped that we might see them again.

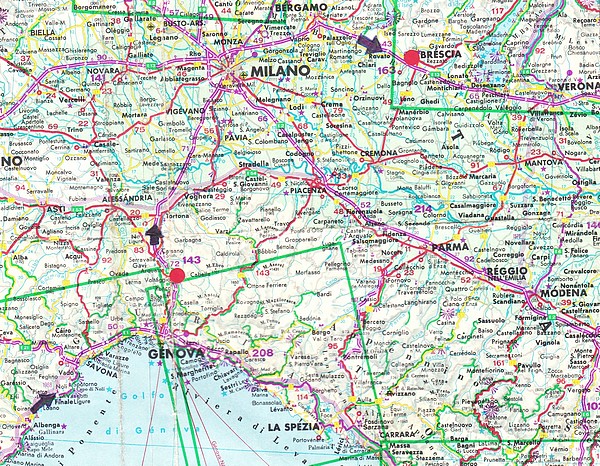

The weather was still overcast as we drove through Trieste and arrived at the frontier into Yugoslavia. No problem arose there and, after changing some money into Dinars, we headed off towards Ljubljana (now the capital of Slovenia) rather glad to have left gloomy Italy behind us. To be fair to the Italians, I'm sure we would have enjoyed it more if the weather had been better!

Once again we found the change on crossing the border very vivid and sudden. The landscape became steadily more attractive as we headed inland and the people were friendly and natural, even if the police did have red stars on their hats! Unfortunately the national fuel, Yugopetrol, was of very poor quality (as was the road surface) and even Dougal's rugged motor coughed and spluttered as he climbed the rough road over the hills, and the outside temperature dropped noticeably. While stopping in a small town to buy some bread and eggs at a state-run supermarket, the girl behind the counter smiled at us and morale rose.

Dougal rolled into Ljubljana at half past eight and immediately attracted a crowd of inquisitive onlookers - so many, in fact, that traffic was blocked by the number of people standing in the road. We found this embarrassing and locked up the van to explore the city on foot. A young chap carrying a guitar, along with two of his friends, befriended us and took us to a self-service cafeteria for a meal. This municipal canteen was rather like a NAAFI, providing an excellent hot meal for 25p and government cigarettes at 8p for a pack of 20. Our host, Drago, spoke excellent English. After the meal he invited us to his flat and we entertained them with music from John's tape recorder, as well as playing some guitar together. Drago was very good and we listened to him until 1:30 in the morning while his friend Andrew provided cups of tea. The van was parked up on the rough grass forecourt of the block of flats, and we eventually got ourselves some very welcome sleep. John wrote in our log "Everybody stares at Dougal here."

The next day we decided to have a bath. We learned that there were public baths in the town so we set off to find them. John reversed at great speed out of Drago's drive and hit a concealed tree stump with considerable force. We surveyed the damage and found that the chassis had been badly bent underneath. The bath was accordingly set aside and we drove around town trying to find a garage who could sort the problem out, but failed. So we returned to Drago's place and did the job ourselves with a hammer and brute force.

Later, after finding the bath (which turned out to be a shower), visiting the shops to buy a few provisions and some very expensive colour film, and writing letters home in the Post Office, we changed and joined the others for an evening of dancing. The discotheque was situated under a very modern sports centre, and the music was surprisingly up to date. I won a record with a lucky number on my entrance ticket (a song that John hated) and John put all his charm to work on a young American girl. I chatted to Drago about life in Yugoslavia, and he told me how they hated the Russians who apparently feared Yugoslavia for its military strength. I couldn't help admiring the bold confidence of these illusions, and wondered if Czechoslovakia had felt the same way before the Soviet tanks rolled into Prague.

It was time to leave Ljubljana and the Slovenians, so we said farewell to Drago and Andrew, while accepting the invitation from Drago's friend Joe to spend our last night parked outside his house. Joe made us some coffee and played records from his vast collection (mail-ordered from London) and then we went out into the rain and parked Dougal in his front garden as he kindly suggested.

In heavy rain next morning we were provided with breakfast and hot water by Joe's family and then, after another visit to see Andrew, left to join the Autoput bound for Belgrade and the south. Our stay in Ljubljana had been a very pleasant one and it proved that bad weather didn't necessarily prevent enjoyment for the traveller. The city was inexpensive, traditional and charming, and the people, though very inquisitive, were warm and helpful without exception. Altogether we found it the most stable and satisfying city of our entire journey, and were quite amazed by the size of the curious crowds that would gather around Dougal. John wrote in our log "Bread is very hard to get here, and is bought very quickly."

The road south was a real challenge, divided equally between three different surfaces - concrete, cobbled and asphalt. The concrete parts were good but very narrow; the cobblestones made a tremendous noise but were reasonably even; but the asphalt was very poor and breaking up everywhere. There was no sign of any attempt to restore its quality and the result was devastating to our bones, the suspension and the van's contents. We kept hitting pits or unexpected bumps at speed with a bone- jarring thud, and sometimes had to slow down to walking pace in order to avoid great holes and steps in the surface.

The travel brochures listed this as a motorway, running down through the vast central Serbian plain from Ljubljana to Belgrade, a distance of nearly 400 miles. It was only a single-lane road for its entire length and carried a surprisingly small volume of traffic. The poor quality took its toll on the Yugoslavian vehicles with a vengeance, and every few miles we saw some truck or car in distress. Sometimes it was only a puncture and the driver would be jacking up his massive truck to replace a wheel, but often a tanker or lorry would be lying upside down in the adjoining fields, victim of a blowout or suspension failure. Large cars seemed less susceptible to this, and they travelled at great speed with no apparent adverse effect, but total wrecks of the larger commercial vehicles were commonplace. We hoped that Dougal would survive unscathed - we didn't relish changing a wheel in the rain.

The Autoput seemed interminable, largely because it never actually went through any towns, just providing turn-offs whenever church spires and towers on the horizon indicated a settlement to the right or left. We therefore passed Zagreb without seeing it and drove on steadily into increasing darkness. At 11 o'clock we saw the lights of Belgrade ahead of us and the airport loomed up on our right. Feeling utterly exhausted and having covered 330 miles since lunchtime (and 2,000 miles since we left home), we pulled into the airport and, being too tired to investigate, parked under a flyover and fell fast asleep.

Belgrade Airport; a Tupolev Tu-134 airliner from East Germany. 2 April 1970.

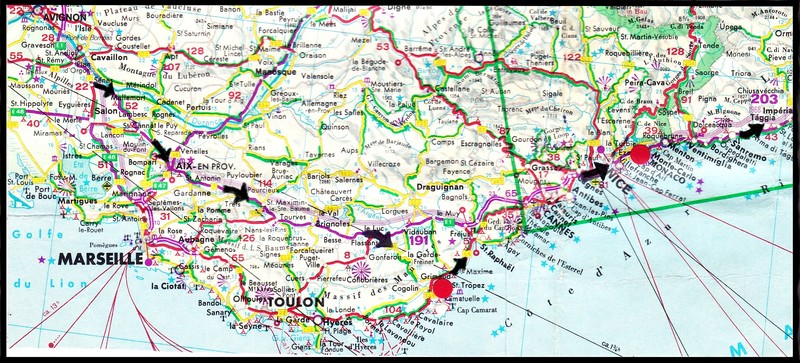

A jet woke us up in the morning at a very civilized hour and we drove up to the airport terminal for a wash and brush-up followed by some coffee. The tourist counter provided us with a map of the city and John ascertained the position of the British Embassy while I looked at the aeroplanes. We had two duties in Belgrade, the major one being to obtain a Bulgarian visa, since we intended to visit Sofia (and possibly Varna and the Black Sea coast) en route to Istanbul, although we had very little information about the roads in that area. Our second task was a visit to the British Embassy to see if they could enlighten us about road conditions. If the road from Varna to Istanbul was impassable, as we suspected, then we would go through Greece instead. Initially it all hung on whether we were able to obtain a Bulgarian visa.

Belgrade was a bustling city with a lot of character, a fleet of rapid noisy trams with a total disregard for pedestrians, and many beautiful young ladies. We found the Bulgarian Embassy and they reluctantly gave us our visas on the spot. This was a good start, but we drew a blank at the British Embassy with regard to Bulgarian road conditions. The Consular Section was most apologetic but explained that, although tourists were always requesting such information, those who actually visited the areas never relayed any details of the conditions back to the Consulate. They did suggest, however, that all roads south were poor and the one from Varna probably closed.

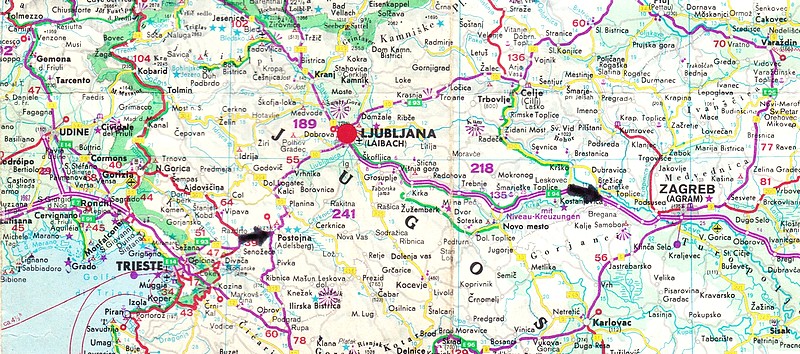

Mountain road in southern Yugoslavia. 3 April 1970.

We went for a meal of something traditional (which we guessed was lamb chops with spiced, fried cabbage) and, after studying maps and considering the possibilities, decided to reach a compromise and route through Sofia and then south into Greece to follow the Aegean coast into Turkey. We had very little idea of the condition of any of the alternative routes but this appeared to be the best bet. We had chosen the worst one of all, without knowing it!

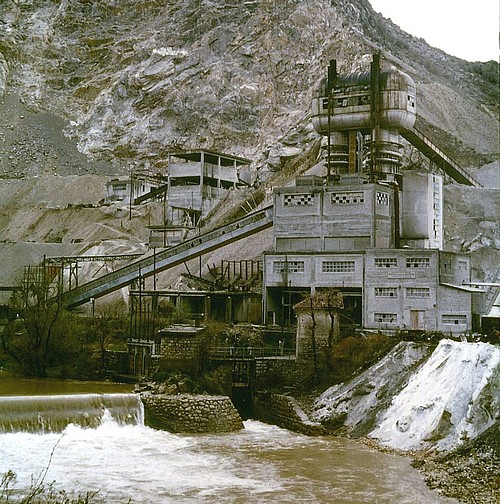

There was enough time left before dark to reach Nis (pronounced Neesh), an industrial town in the Balkans about 70 miles south of Belgrade. It made a pleasant change to leave the central plain and wind our way up into the mountains, although it became appreciably colder as we did so. The face of Yugoslavia changed vividly, settlements becoming more remote, and simple farming becoming the primary way of life. The exceptions to this were isolated mining and quarrying facilities, often in a poor state of repair, providing an alternative employment for those tough enough to labour at extracting stone or ores from the barren mountains. In the midst of this bleak district stood Nis - sprawling, smoky, dirty, and thriving industrially on the diet of coal and mineral ores that the area provided. Population density was high and standard of living low, our first real taste of industry behind the iron curtain.

Quarry installation in the mountains south of Nis, Yugoslavia. 3 April 1970.

Despite a fine of 50 Dinars (about £1.75) which John incurred for contravening some obscure overtaking law, and notwithstanding the use of our spare petrol supply when we ran out of fuel about 8 miles short of the town, we arrived in Nis at about 6:30pm and found the locals curious (as ever) but friendly and cheerful. There was only one campsite, fortunately outside the city and attached to a motel. Though obviously running at half power, being out of season, the camp provided adequate comfort and even a little company in the shape of a Land Rover full of people travelling to Calcutta with one of the organised overland trek companies. We found them cold and reserved at first, but after some persuasion they joined us for a drink in the busy motel and loosened up a little.

We were joined by three jovial Yugoslavs who tried explaining the subtleties of the Serbo-Croat language to us in French and German, and the whole evening began to deteriorate thereafter due to the hidden powers of Serbian wine. Finally we serenaded the unfortunate travellers on our guitars and then fell into our beds. Waking in time to see the Land Rover party leave, we enjoyed a huge breakfast and then left the grime and smoke of Nis behind us and turned east towards the Bulgarian frontier and Sofia.

The road from Nis to Dimitrovgrad, southern Yugoslavia, 3 April 1970.

The road started well but soon turned into an appalling track through the mountains. Where broken fences at cliff edges indicated fatal misjudgments by previous motorists, locals had the grim habit of placing wreaths against the fence-posts, and these were far too common for comfort. However we were struck by the stark beauty of the area, something which the rare traveller in this district could not help but admire, from Bulgaria and Greece west to the Adriatic. We finally reached the frontier at Dimitrovgrad after several miles of grim certainty that a puncture, or worse, was inevitable. In fact we were extremely lucky with our punctures, as most groups we met had suffered several by this time (the Calcutta-bound Land Rover in Nis had already incurred seven since leaving London), and we managed to reach Persia before our first wheelchange.

This turned out to be one of our more eventful frontiers. Leaving Yugoslavia was simple but the Bulgarian post, about 100 yards further on, presented a problem straight away. Publicity material that we had been given by Balkan Tourist in London clearly stated that "Vehicle insurance is optional in Bulgaria, but the International Green Card is valid". So when we were asked to purchase Bulgarian insurance for about £2 and were told that the Green Card was NOT valid, we objected strongly. Immediately everyone seemed incapable of speaking English any more, and John finally turned on an unfortunate girl sitting behind the tourist counter. She only spoke French but that was better than nothing, so we yelled and screamed at her (very unfairly) to everyone's amazement. We produced the offending publicity material, we spelled each word out to the poor girl, we jumped up and down, and finally tore up the brochure in the middle of the floor. We were beaten of course, so we paid up and went to the bar for a drink. Then who should walk in but our three colonial friends in the Bedford who we had first met in Venice. That was an excuse for another beer and prolonged chatting.

While the other lads were dealing with their formalities I sent a postcard to the British Embassy in Belgrade thanking them for their help and giving them information about the state of the roads and our insurance difficulties. Meanwhile John, in his inimitable fashion, was busy buying a drink for the girl from the tourist counter. She was looking very furtive and uncertain since it appeared that she was really not allowed to drink at the bar, but she gave in to John's charm and he was soon caught up in his best chatter routine, despite the handicap of having to conduct it in French. Indeed, he managed to arrange a date with her for the following evening at 6 o'clock outside the Hotel Piska in Sofia.

After about twenty minutes two soldiers armed with machine guns approached us and pointed out that our van was blocking the thoroughfare. We left Zena and the lads and prepared to depart for Sofia but, as we drove towards the final barrier releasing us into Bulgaria, the guards indicated that our clearance was not yet complete. Dougal was guided into a large shed with an inspection pit on the floor and the doors were closed behind us. Floodlights came on and a team of officials began to inspect our van from top to bottom, while armed guards stood by. Chassis members were tapped with little hammers and even our transistor radio was taken apart, being particularly suspicious because it didn't work. John assumed that we must have displeased them with our demonstration over the insurance and our distraction of the receptionist, as we later found out that our friends in the Bedford weren't given this treatment.

Finally they released us and we set off down the 30 miles of four-lane motorway to Sofia, possibly the best piece of road in the country. Our arrival in the city coincided with the rush-hour and the cobbled streets were a mass of bicycles, trams, trolleybuses, articulated buses (rare things in those days), taxis, cars and scooters splashing their way through a steady downpour. In spite of a map we had brought from England we soon became completely lost and finally appealed to a passing chap on a scooter by shouting the word "Camping?" He indicated that we should follow him and led us at great speed through the hazardous traffic across the city and onto the road to Plovdiv in the south-east. The camp was a few miles down this road but, being out out of season, most of the facilities were unavailable and it was more or less closed. However, we were admitted free and John began to investigate the boiler room to find out how to switch on the hot water.

Later, having eaten and washed, we visited the camp restaurant for a beer and a chance to write up our log book. Entertainment was provided by a three-piece Bulgarian folk band led by a hideous, leering violinist whom we christened Svengali. Suddenly, in walked our three friends from the Bedford van so the rest of the evening was spent in the restaurant and in their Dormobile exchanging stories, information and Yugoslavian plum brandy.

Next morning the weather was no better and a frost lay on the grass around the campsite. John managed to produce hot water from the boiler room again, and we prepared for a day of domestic duties such as washing clothes and cleaning the van. The others were leaving for Greece and we bustled about, getting in their way as they made ready to depart. The South African lad asked if we had seen the name they had now painted on the back of the Bedford. We were puzzled to find THE WART inscribed on one of the back doors but, not wanting to upset them, we admired it dutifully. However, with the other door closed, the full name of THE FLYING WARTHOG became apparent, and this made a little more sense. When they were ready to go, their van wouldn't start and we had to give them a push, but they got away finally and, though we arranged to meet them again at the Silivri Mocamp in Istanbul, we never saw them again.

Later that day with our washing hanging out to dry and soap suds all over the van, we were visited by a little VW Beetle containing two men. One of them, a heavy fellow in a long raincoat, spoke English fairly well and asked us a lot of questions, but we couldn't establish the object of his visit or his identity. After they left we discussed the incident and came to the conclusion that they must have been in some official capacity, and that we were probably being discretely watched or followed. This feeling, justified or not, was aggravated by the discovery that John had lost his cigarette lighter. He remembered that Zena had playing with it - rather dangerously at times - at the border post and it had not been seen since. We now began to wonder if Zena had deliberately withheld it so that it could be fitted with a transmitter or tracking device, and that she would return it that evening when we met her for John's date. Just how seriously we took all this at the time I'm not sure, but I know we became very careful and suspicious from that point, and were inclined to leave Bulgaria without too much delay.

That afternoon we decided to visit the airport prior to meeting Zena. We walked into the terminal at about 4 o'clock to find it a very forbidding place full of armed guards and security men. It was built like a rather drab cathedral with a high ceiling, hardly any windows and dim chandeliers suspended way up in the roof. I would have liked to photograph some of the aircraft (all Soviet-built) but thought better of it in light of the armed patrols and our current paranoia. However we did take the opportunity to set our watches and found that they disagreed with the airport clock by one hour. After checking this with some airport staff we discovered that, on entering Bulgaria, we had passed into a new time zone and should have put our watches forward by one hour the day before. This was a revelation but it also meant that, instead of being half past four, it was now half past five, and we had only half an hour to reach Hotel Piska and meet Zena by 6 o'clock.

We made it on time and stood outside the hotel entrance peering self-conciously at surrounding office- block windows for men with binoculars or cameras. After a while Zena arrived with her brother Sacha and his fiance Helene. Zena promptly produced John's cigarette lighter which we regarded with great suspicion, making a mental note to inspect it more closely later.

The entire party bundled into Dougal which was then guided around the city, winding up in a small flat occupied by three student girls (friends of Helene's) living in somewhat austere conditions. Balkan cheese and wine was served, along with beer drunk out of jam jars, as we were subjected to a barrage of questions about English life and the world outside. The girls were all studying English Literature at the university, which made communication easier and, as part of this syllabus, they had to read and write in Middle-English and Anglo-Saxon. This remarkable achievement put us in a little difficulty when they asked us to check some of their work!

The modern American literature that they had been given to read consisted entirely of cheap, sleazy paperbacks, war stories and third-rate bookstall crime novels. They had neither read nor heard of Twain or Hemingway or other contemporary Western authors of any repute, and had built up a vivid impression of the whole world outside the Iron Curtain as being totally corrupt and violent, fraught with war, crime and drugs. We spent the evening trying to dispel this impression, but were only partly successful and didn't mention how we felt about conditions in Bulgaria.

The girls invited us to round off the evening with a song, so we got out our guitars and obliged but it was received with doubtful appreciation and we gave up. It appeared that there was to be a student dance the next night and the girls asked if we would stay in Sofia and attend it. We agreed and then left with Zena, Helene and Sacha to take them home. It was after midnight as we rumbled across the cobbled roads heading back to the camp. The sparse lighting glowed feebly onto a deserted city, looking even more grey than usual. Not a single vehicle passed us except a small tanker with a crew of women hosing and brushing down the cobblestones and pavements. A handful of single-deck trolleybuses lay silent outside their depot, collecting frost on their roofs in the moonlight. Sofia at night had a character all its own, but not a particularly jolly one.

Dougal in Russian Square, Sofia. 5 April 1970.

The next day was Sunday and Helene had invited us to a conducted tour of the city, a job she did professionally in the summer, and we were determined to view the place with an open mind, putting aside any preconcieved ideas about Iron Curtain life. We picked her and Sacha up in Russian Square, the Hyde Park Corner of Sofia, crowned with a huge red hoarding celebrating the 100 years since the birth of Lenin. These hoardings, accompanied by posters and flags, lined the streets everywhere in preparation for the big day on 22nd April. Our first visit was to the Russian Monument, a stone memorial in the middle of a large square which, Helene explained, was erected in memory of all Russian soldiers who died in the Liberation of Bulgaria. "The Russians liberated us twice, once from the Turkish yoke and once from the Fascist yoke, so we built this in gratitude" explained Helene, as though reading from a guidebook.

In this fashion we were directed round the city and saw the TV tower, the new and superb sports stadium, the parks and lakes, the radio station and more monuments to Russian soldiers, Bulgarian soldiers, the Russian nation, Lenin, and Dimitrov the national hero. Next we visited the magnificent Bulgarian Orthodox cathedral with its domes of gold leaf. Mass was being celebrated and we watched for a while. "Religion," said Helene "is free in Bulgaria." This turned out to mean that one had the choice of being Orthodox or nothing at all. The cathedral was named after Alexandr Nevsky who financed its construction in about 1890. Helene led us to a crypt below the building where national treasures were on display, including gold and silver religious artifacts and medieval paintings, mostly from the north-east of the country. Saint George featured frequently in these paintings, which were preserved at a controlled temperature and humidity.

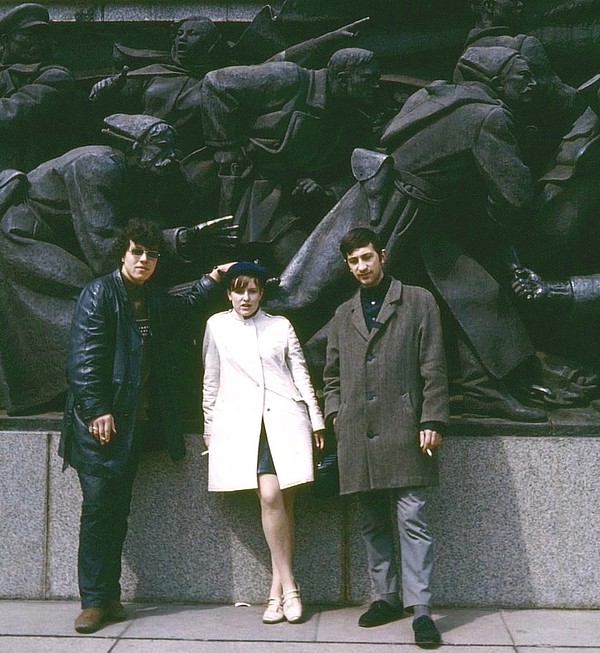

John with Helene and Sacha at the Russian Memorial, Sofia. 5 April 1970.

That night we set off late for the dance because someone had locked us inside the campsite. Having picked up Zena we found that Sacha and Helene couldn't come and the whole thing was cancelled. Since we had to use French to discover what had happened to the dance, it was very hard to divine the real truth, but we had no choice but to accept it silently, like most things in that mysterious country including trying to tell the difference between a soldier and a parking attendant.

While John and Zena made whoopee in French, I got chatting to a friendly ambulance driver about differences between East and West. The driver invited me into his vehicle parked in Russian Square and proceeded to discuss very controversial matters with great fervour. I didn't really want to get involved, especially when sitting a few feet from all the radio equipment in his ambulance, but I listened politely while he told me about the red card earned through loyalty to the Communist Party, without which one cannot hold a decent job. He also told me about local elections with only one candidate (often a total stranger), each voter entering his name and address on the ballot paper so that people not turning up at the poll could be visited later by a government representative; about not being able to leave the country, even to Yugoslavia for a holiday, because passports were only issued to red card holders of long standing. Revolution, he said, was the only answer, and it would happen - the young people would see to it.

Alexandr Nevsky Bulgarian Orthodox Cathedral, Sofia, with a Ford Transit trek van (from a 1970 brochure - we took a photo from the same place, but it was poor quality).

I nervously withdrew at this point and we all went back to the camp restaurant for a Bulgarian meal. John asked for anything but fish, and we all got fish. Good food however, accompanied by Svengali and his swarthy troupe. We took Zena home and I walked around in the night while John made a three-course meal of his farewells, with hollow promises of undying love in French. As we drove back to the site and steered along the narrow driveway, a dark figure leaped out of the bushes and our headlamps picked out a gruesome face leering at us in the darkness. It was Svengali and his violin. He gave us a final ghastly grin before disappearing again into the night.

Next morning we prepared for a rapid exit of Bulgaria. We had to go back into the city to join the road south, so we called at Russian Square to see if the ambulance driver was still there, but there was no sign of him. By this time he could be far away in some salt mine for all we knew. The RAC itinerary informed us that the Greek frontier closed at sunset but, since it was only 150 miles from Sofia we felt there should be no difficulty in meeting this deadline. However the road rapidly became little more than a narrow, worn cart track and the situation was aggravated by the violent undulations in the countryside. In spite of this we were amazed to find huge trucks, sometimes with trailers of equal size, battling across the hills, not without some difficulty.

At one point where the road made a vicious dive down into a little valley, turned sharply left and then rose straight up again, all in the space of 200 yards or so, a vast truck and trailer (known as a split), was stuck at the bottom being unable to pull its load up the far hill or reverse back up the way it had come. We tried to imagine how the problem could be solved - unload the truck perhaps, or fetch a crane 80 miles from Sofia? Certainly no local agricultural tractor would be able to move such a load. Forging on through appalling roads across spectacular mountainous country in great fear for our tyres and suspension, and wishing we had made a different decision back in Belgrade, the sun set at exactly 5 o'clock, and we just made it. The border guards had put on their raincoats ready to leave, and we were definitely the last vehicle of the day.

We had over-estimated when purchasing Bulgarian petrol coupons at Dimitrovgrad and there were a lot left over. Unfortunately we couldn't now convert them back to cash because there was no office of Balkan Tourist at this frontier, so we sold one to a passing Bulgarian and used the others at an adjacent petrol station to fill the tank right up, along with Jerry the can and the stove, leaving only two litres wasted. Customs then searched the van, more out of curiosity than duty it seemed, and sent us on our way. The Greek side was negotiated smoothly, including some money-changing, although we had another half-hearted search and they were most suspicious of Zebedee the bike but, like every other frontier so far, showed no interest in our hard-won Carnet de Passage.

Readers following this story closely may be wondering what became of John's cigarette lighter which had been borrowed by Zena at the Bulgarian border, and which we suspected might have been implanted with a tracking or recording device. Did we examine it for interference? Had it been tampered with? The answer is that I can't remember, and no subsequent note of it was made in our log book. So I'm afraid that story has no satisfactory ending.

Once again we experienced that aura of change having crossed over to a new country. Some things were decidedly different. Better roads and rolling green hillsides made a welcome relief from the wild mountains to the north, and even the twilight seemed to glow through a clearer sky. It was another 60 miles to the coast but we decided to push on and, after four hours of hill-climbing in darkness, playing a strange game of charades to keep ourselves awake, we came over a brow and saw the lights of Thessalonika way below us. We raced excitedly down the hillside and into the bright bustling city, heading for the sea front.

The landmark White Tower overlooking the sea at Thessalonika.

As we paddled in the warm water beside the fishing harbour, memories of a similar feeling at St. Tropez came to mind and so did a considerable hunger, as we had not eaten since leaving Sofia. Not far from the famous White Tower on the promenade was a little shop that sold beer and a food we would call kebab, but they called goulash. This delicious spicy snack became a compulsion, and we gorged ourselves for nearly two hours. Around midnight we found the campsite at Thermopylae, but it was closed so we had no choice but to park on an adjacent beach and put our bloated bodies to rest.

The following day was spent lazing around in glorious sunshine on the beach and exploring Thessalonika, which we found to be a clean and comfortable city. There was plenty to see and we had plenty of time. At the railway station we found a novel machine that polished shoes. I stood on the device and inserted a coin but, though it made noise, nothing happened. John decided to have a go, and he had more success. Black polish squirted out of tubes each side and revolving brushes massaged his boots for several minutes. Unfortunately John's boots were brown suede, but he took it well.

In the evening we visited a club called 2001. It was built like an amphitheatre inside and featured a lot of Greek music. John tried his usual routine on a local girl sitting near us, but was discouraged by a crowd of menacing brothers and friends so we felt it prudent to leave. The day was rounded off with another attack of goulash before repairing to our beach again, having decided to move on down the coast in the morning.

In fact it was nearer the afternoon when we left, as another glorious morning incited us to stroll about on the beach again. We wandered out along a stone jetty and watched shoals of little fish (whitebait or sardines perhaps?) swimming about in the clear shallow water. After amusing ourselves by trying unsuccessfully to hit crabs on the seabed by throwing pebbles off the jetty, we left the beach and went to the airport for a wash. Then, with a quick goulash inside us, we drove off.

A lazy journey along the beautiful coastline brought us to a fishing town called Kavalla (or Kabala) where we found a delightful campsite in a cove. It wasn't the cheapest but it was very clean and provided a restaurant and bar, electricity, hot and cold showers, a laundry and a kitchen. Amongst the other visitors to the camp we made contact with a coachload of 36 Australian girls, and four sailors in a Royal Navy Land Rover heading back to London. Britain was withdrawing its military presence in Singapore at the time and the sailors had talked their senior officers into letting them drive back to the UK in the Land Rover. They had travelled by sea from Singapore to Madras and were completing the rest of the journey overland. Also at the camp were an American family, a coach full of Germans, and a 3-car convoy of Brits, South Africans and Aussies.

The campsite in the bay at Kavalla, Greece. 9 April 1970.

We arranged to have an open-air discotheque that evening and unloaded our record player and tape recorder. John dismantled a lamp post and tapped into the electricity supply to power-up the music, with the guitar amplifier linked up to boost the volume. The hills around our miniature bay formed a natural amphitheatre to contain the sound and gave us a perfect setting. The word soon spread and, when we started the music, a good crowd assembled and the camp manager laid on the drinks. At ten we closed the festivities for the benefit of those who needed their sleep, and moved onto a verandah overlooking the beach.

Blackie, one of the four sailors, produced a banjo and they began to sing a series of West Country ditties and dubious naval songs. We supported them with our guitars and added some traditional folk favourites. The evening was rounded off with cups of coffee provided by the girls and we retired to bed at midnight. We met another new face that night, a hairy German hitch-hiker named Wolfgang who was staying in a room at the camp prior to leaving for Istanbul. He asked if we could give him a lift along the coast, but we were disinclined to commit ourselves at that stage.

Next morning the Navy was very much the worse for wear. Some of them would not get up at all, but Blackie the banjo player asked if we wanted to buy a gun. They had purchased a replica of an Army 7-shot .22 revolver with fifty rounds of ammunition. They thought it advisable to carry a weapon through the Middle/Near East and had bought it in Pakistan where such copies were made in huge numbers, but felt it would become an unnecessary liability once they got into Europe. This had been our feeling entirely except, of course, that we were travelling in the other direction. In fact we had originally planned to buy a gun in Greece but had since forgotten about it. We bought the revolver from the Navy for £5, which they claimed was what they had paid for it, and seemed to us a very fair price. We intended to practice with it in a quiet spot some time but the opportunity never arose and the gun never fired a shot while it was in our possession, which turned out to be a very short period.

Wolfgang, the German boy, asked us again if we could give him that lift and we agreed to take him as far as the Turkish frontier, then leave him to his own devices. So the three of us said goodbye to the Australian girls and a bleary Navy, and left the pretty town of Kavalla to follow the coast and enjoy the sunshine. We changed over the batteries at the top of a hill and headed for Alexandroupolis, having completed 3,000 miles since leaving home.

Wolfgang, it transpired, had left Stuttgart some days before with $7 in his pocket to celebrate having failed the medical for his national service in the West German army - he told us that he hadn't eaten for a week before the exam to make sure that he was in particularly poor shape! He was heading for Istanbul (having already visited the city some years before) and hitched a lift straight away on a truck from just outside Stuttgart to Kavalla. He was also to do well on his second lift, as it turned out. His English was very good, as was his French and Spanish, and he obviously had a very active mind but he chose to travel in great discomfort, having few possessions, next to no money, sleeping rough and eating as little as possible. In fact, as well as sleeping rough he seemed to sleep a lot.

On reaching Alexandroupolis we felt that we had done enough driving for one day and checked in at the only campsite that was open, a rather sparse affair sporting little other than a primitive juke box, and a bar with a young barman serving on one side and the portly manager on the other. After some shopping we visited the neat little airport and sampled some of that traditional Greek spirit, ouzo, which quite took my breath away. Back at the camp we fed ourselves (and fed Wolfgang) and then enjoyed a musical evening. In the log John wrote "Morale high!"

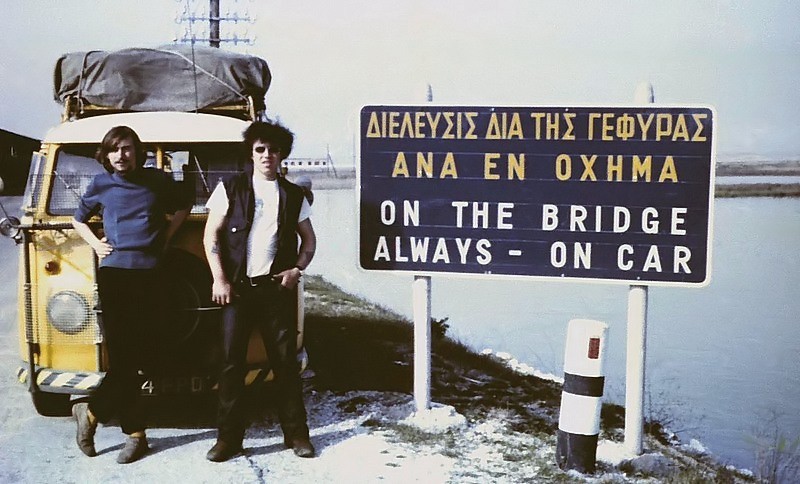

Wolfgang and John beside a mysterious sign in eastern Greece. We assumed it meant "Only one car on the bridge at a time". 10 April 1970.

We rose early and drove off towards Turkey. Our arrangement for Wolfgang was that we would only carry him as far as the border and no further, since his long hair and rather ragged appearance might prejudice our chances of getting through. We had heard that Turkish customs were rather averse to admitting hitch-hikers into the country, especially the more bohemian types with limited means of support. As time went on and we got to know Wolfgang better, this plan was amended and we decided to offload him half a mile from the frontier and wait for him on the other side. However he was a very nice chap and, as we neared the border post, we changed our minds again and decided to chance it. So Wolfgang bundled his long hair into a woollen hat and tidied himself up for the ordeal. After all, if he appeared to be part of an organised party in a van then he would have a far more visible means of support and customs might not realise that he was hitch-hiking.

A narrow bridge across a dyke led up to the frontier, the bridge being lined with sentries in traditional Greek costume, kilts and all. Suddenly the discipline of these soldiers was disturbed by a vast swarm of bees that descended out of nowhere upon the border post. We pulled into the forecourt as chaos erupted, with civilians and officials alike fighting off the teeming invaders. Inside the modern frontier office more confusion was being provoked as a frantic, tearful group of Greeks bewailed some misfortune and screamed abuse at the customs officers. In the midst of all this mayhem our little party passed through almost unnoticed, and a similar indifference on the other side meant that our gamble had paid off and we were all safely in Turkey. For the first time we had found a frontier interested in our Carnet de Passage and we were suitably proud to get the first set of entry stamps in the document; and, for the first time, we were able to record in our log that the weather was hot!

We stopped at a remote wayside cafe for some coffee and made a mistake that, surprisingly, we had not made before; when we asked for coffee with milk we were met with a blank stare from the waiter and in due course were served with a small Turkish glass of thick, brown liquid, a jug of milk, and a tonic water each. Utterly confused we tried every combination of the three and none of them worked. Finally we drank some of the brown liquid and abandoned the rest. Wolfgang who, as usual, had bought nothing, drained our tonic waters and the milk.

Furtively we left the cafe, hoping that the staff had not noticed our confusion, and stepped out into the blazing sunshine. The flat, barren, light brown landscape and dazzling blue sky were overwhelming, as was the heat, and we were grateful to be moving again with all the windows open and a welcome draught cooling the cab. I took the wheel and, with no traffic in sight and the road disappearing straight towards the horizon, I put my foot down. Istanbul was only an hour or two away. Soon the land began to undulate gently in a series of low hills with the endless road appearing at the top of each one, in a perfect line as far as the eye could see. I glanced at the speedometer and to my amazement it showed 75 mph, the fastest that Dougal ever travelled on the entire journey.

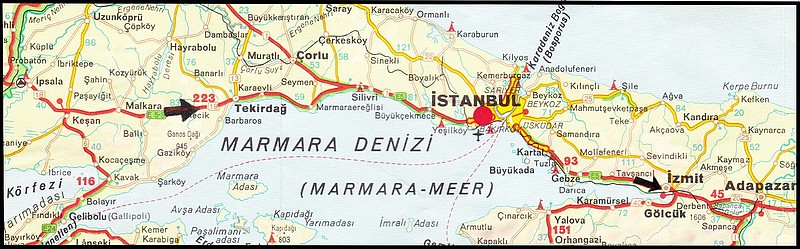

Although, back in Sofia, we had agreed to meet up with the party from The Flying Warthog at the Silivri Mocamp, some 45 miles short of Istanbul, we were making such good progress that we chose to sail past it and continue to the BP Kervansaray Mocamp at Kartaltepe, about a mile from Istanbul Airport, which we reached at 6 o'clock. We felt a great excitement on arriving at this legendary city since it seemed a positive milestone on our journey; indeed, it was Wolfgang's original destination, though he now seemed inclined to travel further.

On arriving in Istanbul we first drove Wolfgang into the city and dropped him off near the railway station so that he could find an ultra-cheap hotel. His previous experience served him well and he shared a roof with various other people in a place that sounded so awful that we never dared to visit it. Then we drove around for a while, exploring.

Istanbul was everything we imagined it to be, but most of all it was a seething mass of humanity. The traffic was dense and insane, consisting of cars, buses, taxis, horses and carts, donkeys and people swarming around the city centre and the waterfront till there was hardly room to move. We found driving extremely hazardous, our worst enemies being the taxi- drivers of which there were thousands. Each taxi, or dolmus, was a work of art. Mostly they were old American cars, DeSotos, Plymouths, Buicks and so on, some of them dating back to the late forties, but we also spotted examples of the Ford Consul and Zephyr, Vauxhall Wyvern, Morris Oxford and Hillman Minx. Condition varied a lot, some being badly rusted and dented, but many were remarkably preserved and lovingly polished. Some cars had no lights, nobody used their indicators (if they had them) and there were no traffic lanes marked on the roads, so you just drove towards any available space.

Classic Istanbul cars, overlooking the Golden Horn towards Beyoglu. Left to right they probably are;

Oldsmobile Super 88, circa 1955, 5.3 litre V8 engine.

Mercedes-Benz 220 (maybe), 1960s.

Ford Fairlane Town Sedan, circa 1956, 3.6 litre V8 engine.

You could board a dolmus taxi anywhere if it was going your way - the driver would pack in as many people as possible and they were always full. A dolmus was usually identified by a band of chequered black and yellow tape, which also served as a warning of approach in addition to the orchestra of blaring motor horns which provided the continuous background music of Istanbul's city centre, despite a prohibition on the use of hooters after dark. Yet the pedestrians ignored all this, spilling off the pavements into the roads and becoming yet another obstruction for the unwary driver who, in this case I must confess, was John.

We weren't able to see much of the general panorama after dark so we returned to the camp somewhat shattered after our first taste of the city. Just as we were going to sleep a Bedford arrived and parked nearby. It was not The Flying Warthog but the other bunch we had met in Venice, the shabby team from Blackheath. What a surprise!

The next day was a Saturday, not the best of days to go job-hunting, but we did. I spent most of the day at the airport in a suit trying to impress Pan American Airways with no success. I would have to return on Monday. We went to the Poste Restante and collected some mail (the first we had received since leaving home) and in the evening picked up Wolfgang and toured the city again in an effort to become more familiar with the geography. It was an amazing experience, full of life at night, teeming with dodgy people on the fiddle, but so exciting.