The Classic British Isles Buses Website

An overland trip from England to Iran in 1970

Story by Richard Gilbert.

Part Three - Tehran to Turkey

Last updated 4 September 2024

Email Events diary Past events list Classified adverts Classic U.K. Buses Classic Irish Buses Classic Manx Buses

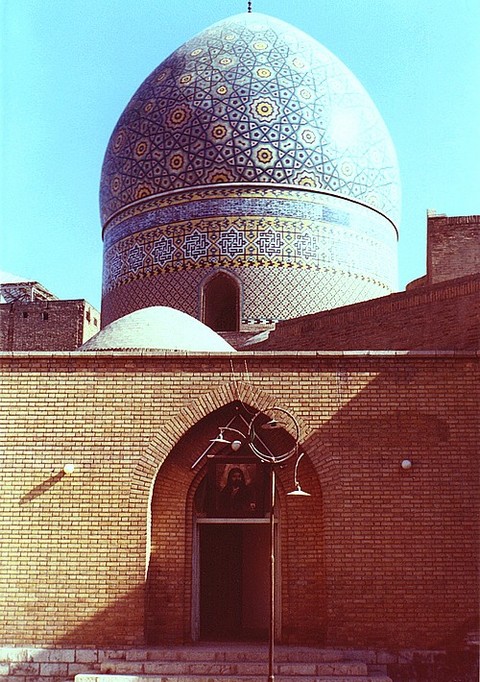

The Shah Mosque, also known as the Soltani Mosque (and now renamed the Imam Mosque) in Maidan-e- Sabzeh, a courtyard by the main entrance to the Tehran bazaar in the south of the city.

After a quick cup of tea and a chat to an Imperial Iranian Air Force pilot in the Plasco building, we took Hamid down to the van and set off for Shemiran. We already knew the first part of the Shemiran Road, being an extension of Pahlavi Avenue and our usual route to the Iran America Society; but as we left Yusef Abad and the other exotic northern suburbs we came into unknown territory. Having passed the Shah's summer palace, the terrain began to rise rapidly and the sandy soil of the south gave way to rich earth, fostering a lush vegetation. The temperature dropped to a comfortable 70 degrees F (20C) and we soon came to Shemiran itself. The part that Hamid had chosen appeared to be a base camp for mountain climbers. A fast-flowing stream ran down a steep, rocky valley beneath an umbrella of trees covering paths, seats, tea houses and little restaurants. Hamid led us up the valley, our path crossing back and forth over the stream on little wooden bridges, and then there we were - a picturesque village in the rocks and a series of stepped restaurants alongside the stream in a gorge.

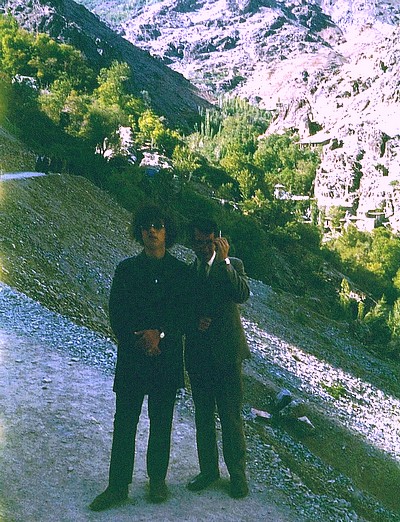

John and Hamid on the path leading up to the mountains in Shemiran. 8 May 1970.

We were surprised to meet some of the young people we had seen at the party the night before, and they invited us to share beer and kebabs up on the rocks where they were relaxing and dancing to a bongo and a violin, Persian-version - no girls. At the top of this little valley a path led up into the higher mountains for the more energetic hikers and climbers. Hamid brought us to a tea shop beside the path and we took the chance to get our breath back and take a little refreshment.

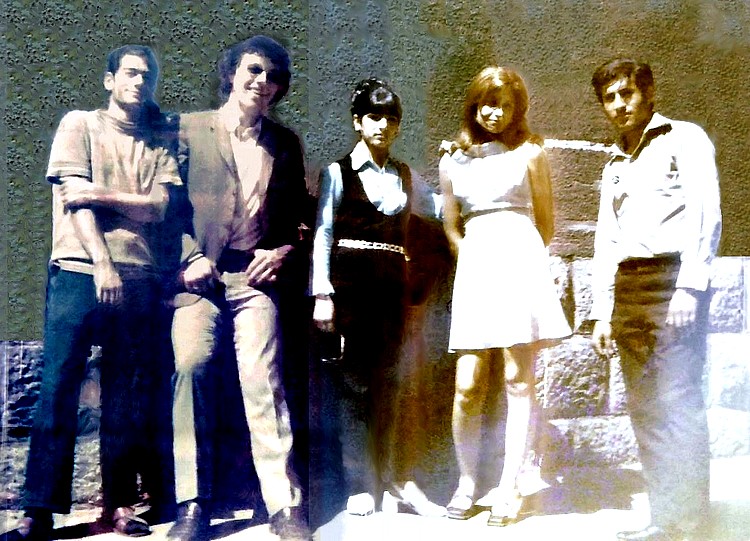

John with some of the lads we had met the party. Shemiran, 8 May 1970.

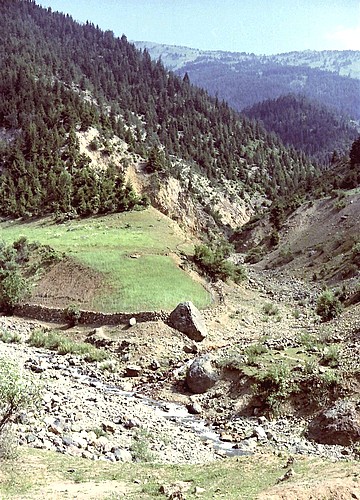

Shemiran was cool, green and beautiful, a welcome change from the dusty heat of the city. Looking back down the valley we could see Tehran laid out before us with 2,000 miles of desert beyond and, behind us, the Elburz Range towering up with Mount Damavand as its peak. The scale of it all was overwhelming and I could understand a little of the drive that kept Persia's ancient tribes nomadic. With a country of such proportions at one's feet, yet with distinct seasonal changes, it would be unnatural to take root. My nomadic instincts were soon to be satisfied again however.

At about four o'clock we decided to leave and took a spectacular chair-lift ride back down the valley to the park at the bottom where we had left Dougal. A group of people was examining the van and, when we appeared, they came over to speak to us. They were part of a BOAC airline cabin crew who were stopping over for one day in Tehran en route from Hong Kong to London. They invited us back to their hotel so, after dropping off Hamid, we joined them for drinks (English gin and Iranian beer) and news from England. They even gave us some English newspapers. We got on very well with them and it was a pity that they had to leave first thing in the morning, and said they only came to Tehran about twice a year. This turned out to be a very enjoyable evening but eventually we made our way back to the campsite where we set about making some new friends, as Michael and Sue had left for Isfahan so we wouldn't be seeing them again.

Spectacular view south across Tehran from the chair-lift, descending from the hills of Shemiran. 8 May 1970.

Residents of the campsite were a mixed bunch. The road from Istanbul to Tehran was not only part of the Asian Highway and the ancient Silk Road, but also corresponded to the route of the infamous hippie trail from Europe to Afghanistan, India and Nepal. In fact this pilgrimage was beginning to lose its appeal for the hard core of original hippies who had hitch-hiked in previous years to Kabul and Kathmandu in search of the freely available drugs and to India for spiritual inspiration of one kind or another. It reached its peak in the early/mid 1960s when droves of broke, long-haired young Europeans, Americans and Australians travelled by train, bus and thumb to the marijuana centres of the east.

At first the locals were confused by their dreamy and laid-back behaviour but soon learned to their cost that many of the travellers would expect to be fed and housed, often free of charge, and they would receive nothing in return, though admittedly the hashish trade became quite profitable. Some fell by the wayside, becoming dependent on harder narcotics and selling all their possessions, including their passports, to maintain the supply. Embassies were beset by stories of lost passports and documents, while local governments were left with the problem of underfed foreigners without enough money to pay their fares home. This gave the whole route a bad name and many frontiers began to clamp down on hairy visitors with little visible means of support, as we had seen.

By the time we arrived on the scene, the restrictions were taking effect and the majority of young people on the journey were taking better-organised holidays in vehicles of their own but, as with most youth fashions, the participant age groups slowly got younger and in 1970 the majority of those who might have been called hippies were youths of 16-18 years. These, even more than their predecessors, found that their inexperience and naivety made them easy prey to sharks, wide-boys and bad influences of all descriptions, aggravated by the fact that some were only travelling because of an unstable homelife in the first place.

Broadly speaking the drug-users fell into two classifications; the first were older and more mature, original hippies who had managed to stabilize their lives, US Vietnam veterans, Peace Corps workers and well-travelled students. A substantial beard was a guide for identification, and Michael and Sue fell into this category, though Sue lacked the beard of course! Their use of soft drugs was selective and in moderation, though it seemed likely that many had experienced stronger narcotics further east but had matured away from them. Indeed many were on the point of withdrawing from the drug picture entirely and within a year or so I expect most had done so. They were quiet and thoughtful (sometimes as the result of a spiritual awakening in the Indian sub-continent), very anti-establishment, generally clean, sociable and intelligent.

In contrast the younger drug users, unfortunately often English, less than tidy but clean-shaven, were indiscriminate in the taking of marijuana and in extreme cases very susceptible to the possible introduction of harder drugs, though I must say that, to the best of my knowledge, I saw no-one using or under the influence of any hard drugs during the entire journey, apart from native Iranian opium addicts. Of course these observations refer only to the proportion of travellers we met who were drug-users, but I would estimate that this was around 25%-30% of the total and decreasing steadily. Certainly the real freaks had mostly long gone, and their trail was becoming fashionable and almost respectable which, I'm sure, made the authentic hippy turn in his flowery grave.

Next day was spent dashing around the city trying to sort things out. We made an appointment to visit the Aliens Office on Sunday, fixed up a job with Asayesh for John, and went back to see the old man in Takht-e-Jamshid about the damaged film. He had managed to extract the spool from the camera but it had torn into two halves, which he had put into two small canisters. I couldn't communicate too well in Persian so, when I tried to find out if he had developed the film, an over-zealous customer in the shop tried to come to my rescue. Unfortunately he would not listen to me but took instant command of the situation and, before I could stop him, had opened one of the canisters to look inside. It seemed that we were destined never to see the pictures on that spool and I was resigned to the fact that we had now probably lost them all, some probably irreplaceable. In fact, of the 36 pictures on the film, it was eventually possible to salvage 22 with the help of experts in London, and some of them came out very well.

The Tehran City Theatre in Pahlavi Avenue, still under construction.

At lunchtime we met Hamid in Park-e-Pahlavi where they were building a fine new theatre in spectacular Persian architectural style. We wandered down Pahlavi Avenue, opposite the sinister Iraqi Embassy with its police guard outside. Relations between Iran and Iraq had always been strained and armed sentries watched the embassy gates day and night, while agents followed all those who came and went.

Meanwhile on our side of the road a small boy, leaning against the park railings, seemed totally unaware of all this as he accosted passers-by to purchase something from a basket he carried. We couldn't see what he was selling but Hamid went over and, in exchange for a few Rials, selected from the basket one of hundreds of small pieces of rolled up paper. Inside were a few words in Persian, much like the mottos and proverbs one finds in Christmas crackers or Chinese fortune cookies, except that this was a quotation from a poem by Hafez. Hamid read the excerpt, taken completely out of context from the poem, and explained that with a little thought one could extract from it a kind of astrology reading for the day. It's interesting that this form of fortune-telling in a highly religious nation should be based, not on the Koran, but on traditional poetry, an indication of the importance of the ancient poets to the modern-day Persians. The famous names of Hafez, Sa'adi, Rumi and Ferdowsi were revered throughout the land and immortalized not only by their works (quotations from which were on the lips of everyone) but also in statues, stone memorials and elaborate tombs and mausoleums in the towns of their birth.

A statue of the poet Ferdowsi dominated Tehran's Ferdowsi Square.

Hamid was in one of his jolly moods, making him embarrassing company, and he insisted on passing frivolous comments to other people in the street. This amused the men but shocked the women, much to his delight. Most of the older women, wrapped secretly in enveloping chidoors of browns and maroons, were unapproachably shy and their eyes peered out nervously as they hurried away.

Next morning Hamid came to the campsite and woke us up. We went first to the Aliens Office where we were confronted with an alarming discovery. The purpose of the visit was simply to confirm that our visa extensions were positively valid for three months, and Hamid came along as an interpreter. We found the same officer who had seen us before and explained our problem. He looked at our passports and said that we had exceeded our original 14-day visa and should be out of the country. We pointed out the marks he had made and explained that he himself had told us that we could stay for three months, but he claimed that he would have done no such thing, as he was not responsible for European passports and not entitled to grant extensions. We were directed to the European section where we were told that nothing could be done - we would have to leave Iran and apply for another visa to re-enter. Seven-day exit visas were stamped in our passports and we were told to get going.

We had no choice but to comply, so the only question was where to go for the new visas. Kuwait and Turkey (Trabzon) were the nearest Iranian embassies, and we decided on Turkey, both because it was familiar territory for us, but mostly because driving to Kuwait meant crossing Iraq and that was forbidden. We agreed to leave in the morning and spent the rest of the day in preparation. After explaining the situation to Mr Nejad and also to Bali-Bali at Asayesh, agreeing to start work in two weeks, we bought Hamid a meal and returned to the campsite.

In order to make the journey as painless as possible we unloaded some of our gear (3 spare wheels, 2 cans of oil, the spare engine and John's fishing gear) and left it in a lockup at the camp. The camp manager took us to one side and said that, if we had to go right back to Istanbul, he would like us to purchase a forged blank Carnet de Passage for him, which could be obtained on the black market there for about £8. We said we would try, but thought it unlikely that we would have to travel that far. Finally we had a tidy-up and, after a chat and a strum on our guitars with some English hitch-hikers, we arranged for the night watchman to wake us at six, and went to bed.

To our surprise we were up at six and on the road by 6:25. We stopped off for a fried egg (which, of course, we cooked ourselves) at a little cafe near the airport and then drove solidly all day. Travelling back into the countryside brought home to us just what a difference existed between life in Tehran and life outside it. The road to the border passed through several regional towns with which we were becoming familiar - Qazvin, Zanjan, Miyaneh. Between them, the true rural Iran showed itself. Mostly a uniform brown blanket covered the landscape, brown earth, brown mud houses, even brown dogs, but this was enlightened in the late afternoon when the sun drew orange and mauve reflections from the distant Elburz Mountains. Even brighter than this were the unexpected splashes of green, white and purple distinctive of clothing worn by occasional nomads (some from the Zagros Mountains to the south) and the decorated blue tiles on wayside mosques peering out from the otherwise unvarying scenery. I just loved all this.

Wayside mosque near Qazvin.

As was common to most countries in this part of the world, many properties were surrounded by high mud walls serving the multiple roles of marking territorial limits, providing a real privacy for the occupants (something lacking in most daily activities) and protecting the domain within. Years later, soldiers in Afghanistan would come to know these only too well as compounds. The protection was probably not only from human intruders but also animal ones, the latter only making sense to us after we heard the howling of wolves at night from the campsite in Tabriz, and were told that it wasn't uncommon for them to come down from the mountains at night to the outskirts of the city and raid the dustbins. The habit of walling-in one's property tied in with the high gates and remotely-controlled locks of Tehran houses, something we were not used to in England. The Persians did not, it seemed, trust the Persians. To be fair, high walls also helped to keep places cool.

The country-dwellers were a dwindling community. It was very hard work trying to extract a living from the barren cracked earth and whole villages lay abandoned, their occupants having moved into the towns to cash in on Iran's new prospects. Life for those who remained had some advantages - food was cheap and each day was simple and uncluttered - but their children were leaving in droves to become the second generation of industrial Persians and, as we had seen, they had no intention of returning. It seemed that, other than the oil centres way down south, Tehran was the essential hub of the nation. Although we never visited Shiraz or Isfahan (how I wish we had!) if they resembled Tabriz then their significance would have been minimal, other than to archaeologists, and the Shah who felt that they reflected his ancestry. All the real decisions were made in Tehran, all the important businesses operated from Tehran, the young people flocked to Tehran for their education and entertainment, and that was where the future probably lay.

Dougal travelled well, being relieved of the weight we had left behind, and we had covered a remarkable 417 miles when we reached Tabriz at sunset. As usual in that city the temperature dropped considerably as the sun went down and we found the evening chill rather a shock. John seemed to be sickening for something and, when we arrived at the campsite west of the town and I made a spectacular curry, it made him feel a lot worse. Next morning we changed some money in the town and left for the border. The sun was very hot and John was still unwell as we rolled into Maku, visiting our friend in the cafe for lunch. Then we pressed on again and shopped for our last tank of cheap Persian petrol at a garage just before the frontier. As we drove back onto the road, the engine inexplicably stopped.

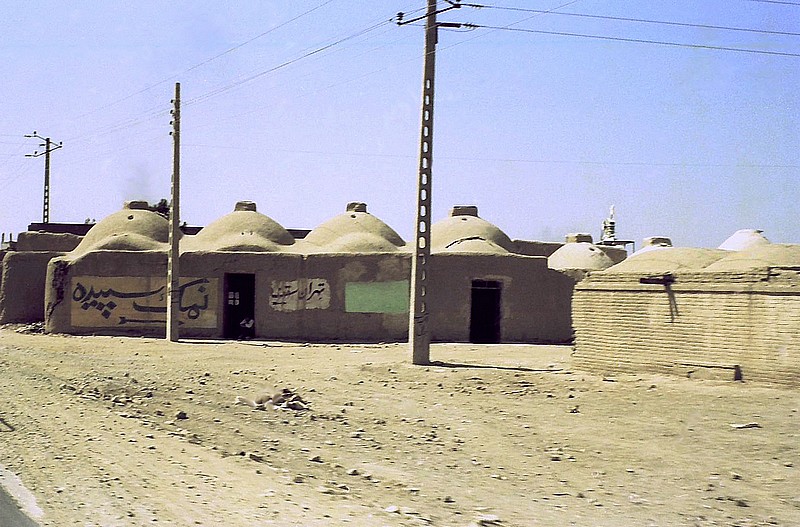

Typical mud houses in Iran (in this case, Saveh Road, Tehran).

After some investigation John drained a little petrol from our tank and found it badly contaminated with water. A rag soaked in the liquid wouldn't burn when we tried it. While John continued to drain the tank I filled a glass with the offending fluid and took it back to the petrol salesman. I poured it on the ground at his feet and all over his boots, then I threw a match at it. He jumped rather fast but nothing happened and we had made our point. However it got us nowhere, as he pleaded total innocence and claimed that he simply dispensed what he had been delivered. We had to empty two-thirds of the tank before we got down to pure petrol, and decided it would be wise to refill in Turkey after all. At the border we complained to the tourist office who promised they would refund the money, but we didn't really expect them to, and they never did.

We crossed the border in 1 1/2 hours, much faster than previously, despite the fact that the same confounded Turkish customs officer brought up the subject of our engine number discrepancy again. During all this we met a young English Royal Marine who was travelling from Singapore to Birmingham on an old Triumph Tiger motorcycle during his leave. It was taking a little longer than he expected and he was running out of time. We warned him that the mountains ahead would no doubt slow his progress even more. We suggested that he travel in convoy with us, especially since we hoped to reach the hospital at Taslicay that night and he would have somewhere safe to sleep. Dr Hikmet was at the hospital and greeted us and Trevor (the Marine) with enthusiasm though his English seemed worse. John was now well enough to make another assault on the little Turkish nurse but was repelled again by her cold indifference, and he spent the rest of the evening annoyed about it. We parked Dougal on the hospital forecourt and, it being a cold night, gave Trevor sleeping space in the cab of the van.

We awoke at 5.30 and, after saying farewell to the womenfolk (including the nurse) and leaving a note for Dr Hikmet, we set off at 6:30 with Trevor in hot pursuit on his bike. The weather had improved considerably since the last time we had passed that way, and the sun was bright and warm. The gravel road led us across rolling green hillsides with the first flowers beginning to show as spring finally burst upon this wild and dramatic district. By 10 o'clock (by which time we had covered 7,000 miles since leaving Eastbourne) we were understandably ready for breakfast so we stopped on a hillside beside a rocky stream and, while John fixed food and coffee on the petrol stove, Trevor and I had a wash in the icy water. A flock of sheep was grazing nearby, attended by a weatherbeaten Turkish shepherd and his young son. The little boy wandered over to examine us more closely.

Just as coffee was brewing, an Australian couple came by on a Honda 350 motorcycle so we waved them down and they came over to join the party. They seemed to be making good progress and things were going pretty smoothly for them, except that they had fallen over on the gravel the day before. Though they were going our way, we didn't expect to see them again, taking into account the difference between a new Honda and a beaten-up 10-year old VW van. John had been cutting bread with a sheath knife and suddenly noticed that the knife had vanished into thin air. He turned on the shepherd boy and threatened him for several minutes with every form of torture possible on a Turkish hillside and a lot that weren't. The result was that the little boy finally produced the knife from behind a rock, an indication of the power of the spoken word in any language.

As we pressed on, the Australians having left us far behind, the weather began to get worse. By the time we reached Erzurum stormy clouds had gathered over the mountains and the atmosphere was humid and uncomfortable. Out in the open country, climbing towards the first pass, we noticed a strange regular ticking noise in the cab. Eventually I spotted the source, a mauve spark flashing between the connections of our radio aerial in the cab just above the windscreen. We stopped and switched off the engine but it kept ticking. Trevor came up to see what was going on and, when he saw the spark, he was afraid to touch the van. Something strange was brewing in the atmosphere.

It was not much further on when we saw the storm heading our way. Half-built electricity pylons dotted across the hills were being struck by lightning and a wall of grey mist bore down on us. We stopped again and shouted to Trevor who was now wearing a vast khaki plastic raincoat. The three of us huddled in the cab and waited. It hit us with incredible violence. Hailstones up to 2 inches across hammered on the roof and windscreen until we felt something must break, if only our eardrums. The lightning got extremely close and we felt very exposed but after only a few minutes it all stopped and we stepped out into silence and sunshine on a carpet of golf balls from horizon to horizon. Trevor took off his plastic raincoat and we set off again.

We made better progress after that, interrupted only by an alarming incident when we came round a blind corner and found two soldiers erecting a telephone line across the road. We stopped in time and immediately remembered Trevor. He roared round the corner after us, managed to avoid the van by coming alongside and squealed to a halt with the telephone cable at neck height just in front of him. The friendly town of Bayburt once again was placed ideally for an overnight stop and we introduced Trevor to the delights of Turkish rice-pudding. Bayburt, which certainly dates back to the bronze age, was an important settlement on the ancient Silk Road (visited by Marco Polo), and is dominated by a castle which can trace its origins to 2000 BC. Curiously Dougal wouldn't start in the morning. This had only happened twice since leaving home, both times in the same town. We felt it might be the altitude - Bayburt was 5,000 feet up in the mountains. Once again our spectators provided the necessary manpower to get us moving and we set off for Trabzon, stopping only at Kalkanli to chat to the German-speaking hotelier whose name we learned was Azmi.

We experienced the same electrical freak twice during the day as the weather got worse and worse, and John's health did too. Trevor's bike was having serious problems with worn teeth on the rear sprocket, meaning that on steep hills his drive chain just slipped round and the bike went nowhere. Every time the chain slipped it wore the teeth away even more until eventually, about 20 miles short of Trabzon, it was just impossible to continue. Trevor, utterly miserable, came in from the rain and sat in the cab with us. For a Marine he lacked initiative, we thought. Finally we got him to stand by the road and flag down a passing truck. We watched as the bike was loaded on the back in company with a soggy goat, and Trevor joined them, there being no room in the cab.

We followed the truck for a while but lost it before we reached Trabzon. All this tended to distract us from the minor discomforts of a van that leaked and had virtually no brakes. We searched the town for Trevor and found him treating the truck driver to a meal. We agreed to provide him with sleeping space again and settled at the same petrol station at the east end of the sea front. Sitting in the cab with the rain coming in round the edges of the doors, John feeling ill, Trevor's machine undriveable, no petrol, no Turkish money, no brakes and all of us hungry, morale was at a pretty low ebb.

Trevor had decided to load himself and his bike on a boat for Istanbul next day and see if he could get a replacement sprocket there. Unfortunately it was a Friday and we felt our chances of finding the Iranian Embassy open were slim. We were right but, with a little determination, we got them to agree to provide us with three-month visas by lunchtime. We returned at mid-day and found we had been given one-month entry visas, and were told that they were renewable on request within Iran. We hoped they were right.

The Turkish mountain road in better weather and visibility than our first visit. 16 May 1970.

Trevor and his bike boarded the good ship Ege along with the two Australians and their Honda. We said our goodbyes to them all and at 1 o'clock the Ege sailed for Istanbul and we left for Tehran again. The weather was much better and the drive over the Zigana Gecidi pass was pleasant and interesting, as we were now able to see the striking scale of this mountain range, previously denied to us by poor visibility; but, being now mid-May, it seemed that summer was finally setting in. After another tea break at Azmi's hotel, we docked for the night at Bayburt once more. The justification for stopping at the same places each time were the remoteness of the area (which gave us little choice), the convenience of their locations along the route, and the friends we had made in the towns who were always hospitable and pleased to see us again.

Outside our favourite rice-pudding emporium was a British Land Rover belonging to Minitrek Expeditions, a well-known overland trek organization based in Surrey. We went in and approached them carefully, remembering the cold reception we had received from a similar party at Nis. To our surprise they cut us dead. We were staggered. It's extremely embarrassing to greet a group of people in a restaurant and be totally ignored. This behaviour by the organised trek travellers really began to annoy us, and it was clearly due to an attitude bordering on snobbery. Those on package trips seemed to regard the home-grown expeditions as low-life at the bottom of the food chain and dismissed us as wayward hippies. Well, I bet we had put a darned sight more effort and planning into our journey than trippers who had bought their packages off the shelf as it were, and I'm sure we saw more things and met more people! Hah!

Next morning followed the usual pattern in which we were woken by the Trabzon bus driver wailing on the other side of the road and, after a little shopping, we prepared to leave and Dougal - of course - wouldn't start. The extraordinary regularity of this fault had to be more than coincidence; either there was a climatic cause or Bayburt must be sitting on some mysterious ley line with a grudge against Volkswagens. At any rate we received more than our usual share of assistance in the form of a Jeep which towed us up and down the cobbled main street until Dougal got started.

It's a full day's hard driving from Bayburt to Taslicay if your steed is an underpowered 10-year old van, and we were grateful for the distraction of beautiful scenery and good weather. We were beset once more by the attentions of the local children who begged us for cigarettes or threw stones at us, or both, as we passed. We had learned to keep an armoury on the floor of the cab, including stones, pine cones and our old apple cores to return the fire. Occasionally we tossed fireworks out of the window, although these usually proved to be more a source of curiosity than panic as intended. Another tactic we employed was waving at the young snipers. When approaching a group of children we might see some of them bend down and pick up stones. We found that, if we leaned out of the window waving and shouting, they would either be stunned into inactivity or would wave back, sometimes even putting down their stones in the process. By the time they realized they had been duped we were out of range.

It was just after 7 pm when we arrived in Taslicay and, after feeding ourselves, we went looking for Doctor Hikmet. We found him in the local tea shop playing a modified game of draughts in which both the black and the white squares were used. We stayed for a while at his invitation but the shop seemed rather oppressive so we went to bed early. We were on the road by 8 o'clock, through the border in 45 minutes, lunched in Maku and arrived at Tabriz in the early evening, quite exhausted and with Dougal so hot we could have fried an egg in his hub-caps, if he had had any.

The Elburz mountain range seen from the Tabriz-Tehran road.

On the final day we negotiated the 420 sizzling hot miles back into Tehran. It was a harsh and merciless road with scarcely a change in the character of the landscape along its entire length, although it certainly had a powerful and lasting appeal to me. The constant backdrop of a purple mountain range in the distance was something that could be found all over Central Asia. I saw exactly the same thing many years later in Uzbekistan on a different branch of the Silk Road and it was quite an emotional experience which took me right back to 1970. The road surface from Tabriz to Tehran was pretty good, and a decent speed could be maintained most of the way, but it was this speed factor that had led to a series of accidents that we came across during the day.

The first was a Danish split that had slid off the road into a stream near Tabriz. The driver had gone to sleep at the wheel. His load was spirits and cigarettes so there was a real danger of robbery if he left the wreck unattended. Unfortunately he spoke only Danish, so he was extremely lucky that the first passer-by was a Danish hitch-hiker! Perhaps foolishly, the young lad agreed to guard the truck while the driver went for help. He stayed for two days and nights, and the local people brought him food and wine but, luckily for him, no attempts at theft had been made. We arrived just as the driver returned with a breakdown vehicle and police. The boy was very relieved and we gave him a lift into the next town while he related his tale. He said the driver had promised that the haulage company would pay a substantial reward for his services.

Truck hit by landslide near Tabriz, being passed by a locally-assembled Mack.

Further along the road one of the splendid Mack trucks that formed the backbone of Iran's internal transport system had been struck by a landslide and knocked over - 420 miles of road, about two vehicles per hour, and the only landslide managed to hit one! It just wasn't his day; either that, or he wasn't paying attention and drove into it. Nearer Tehran a long, flat articulated lorry carrying a big road-roller had jack-knifed and tipped over, completely blocking the road (traffic took a diversion into surrounding fields). Removing the roller must have presented a formidable problem. It was not surprising that accidents happened, since some of the vehicles were feeling the strain, to say the least - including Dougal, frankly. The chassis members of some trucks were so distorted that the vehicle would point ten or fifteen degrees away from the direction of travel.

We got back to the campsite in the late evening and fell straight into bed. Our first action in the morning was to hurry to the Aliens Office with our new visas to confirm the availability of extensions. We were told no. Eight days and 2,000 miles for a dud visa. When we told Nejad about the visa he advised us not to worry and put us in touch with a policeman, who knew another policeman, who bought us cups of coffee, talked about his holidays in America and said he would renew the visa himself when the time came. We never knew what to make of promises like that from Persians, but at least we had a month to think about it. At this point our speedometer broke, reading 54,080 miles in total, of which we had travelled about 8,500.

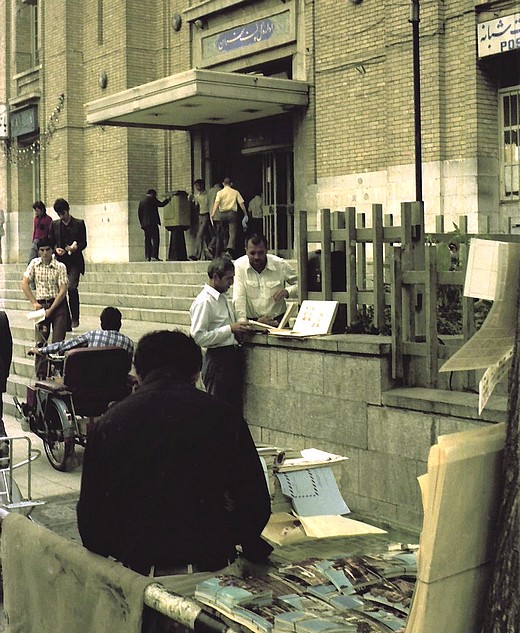

We were now entitled to move into our new home on The Roof, so essentials were unloaded from Dougal and carted up the ten flights of stairs out into the sunshine. Most of our goods were stored in the toilet-cum-bathroom which we could lock, while the beds and stove sat out on the open roof and sank into the tar in the heat. We could also lock the door leading to the stairs so our home was fairly secure, which was important as pilfering was common. We heard of one hitch-hiker who slept on the steps of the main Post Office under the street lights, using his rucksack as a pillow to make sure he didn't lose it overnight. When he awoke his pillow had gone and his head was resting on the stone steps. He hadn't felt a thing.

The Tehran Post Office in Sepah Street.

It was now time to start work, and John went round to Asayesh to see how they were getting on with his office. He spent most of the day rearranging the furniture, trying to discover what his duties would be and making sensual Persian remarks to the little secretary. By five o'clock he had convinced her that he should give her a lift home. Unfortunately in Iran these things were seldom simple, and Bali-Bali suddenly bounced out of the shadows to see what was going on. John explained his intentions, to which Bali-Bali objected most strongly, claiming that it was he who took her home. John pointed out that after 5 o'clock she was anybody's, so to speak, and the resulting clash of opinions left Bali-Bali standing at the door of his office shouting a tirade of abuse at John as he stormed off down the road.

And so it came about that John started work at the Nejad School with me, despite the fact that he still refused to cut his hair. We had one more day of rest before starting at the school and, it being a Friday, Nejad had invited us to spend the day with his family on a picnic near Karaj, in the mountains to the north-west.

We all bundled into Nejad's new VW Microbus which he drove at breakneck speed out to the hills, stopping alongside a wide stream with woodlands on the other bank. The water was so cold that we could feel the temperature drop as we crossed over the road. Mrs Nejad and the three young daughters brought up the rear as we followed over stepping stones onto the opposite bank, through the trees and out into a huge garden. There was a party of some sort going on, to which we were welcomed as guests. Soon some of the men grabbed low tables and placed them in a line down the middle of the stream. Blankets were laid over the top and all the food and drink was transferred to this new surface. Finally the guests sat cross-legged on the tables surrounded by goodies and proceeded to get drunk on Persian vodka.

Certainly it was a marvellous way of keeping cool but to John and me it seems very strange and surreal. By the early evening Mrs Nejad felt the children ought to be taken home but her husband was more than a little inebriated. We roared back into Tehran with the bus performing remarkable feats, and drew up just west of the city outside a small bakery. Inside, the baker selected some lumps of dough for us, flattened them into discs and sprinkled them with spices. He loaded them into his oven over stones and we watched them cook while wallowing in the appetizing smells. Finally he withdrew the finished articles with his long wooden spade and handed them to us. Driving back into Tehran munching this hot fresh bread was a delightful experience.

The teaching business turned out to be a relaxed affair, aided by the enthusiasm of the students, the air-conditioned classrooms and the daily siesta from 12 to 5 o'clock each afternoon. Initially I sat in with other teachers, holding simple conversations with the students, correcting pronunciation, reading passages and advising when necessary. This had a side- effect, in that my Farsi began to improve at a great rate. The other teachers seemed pleased to have a real Englishman attending the classes and the students were equally enthusiastic.

Because of his hair John was not permitted to teach but, while he thought about it, Nejad employed him as an electrician, among other things. He started by repairing the many broken air-conditioning units, and then progressed to the complete rewiring of the building. This vast task enabled him to sit on a stepladder in a corridor and chatter to the more attractive female students. In fact, if he found a good strategic position he could chatter all day, do no work at all and have to return to the same place next day. It took Nejad a long time to discover this, and meanwhile John continued to postpone the haircut.

Nejad had a passionate faith in advertising in every form. The school building was covered with writing in both Farsi and English, and crowned with a huge red neon sign that stood out above surrounding rooftops and made an excellent landmark if we got lost. During the school's history Nejad had devised a host of advertising schemes and on quiet days at the school John and I became involved in two of them. The first was a small folded card about the size of a cigarette packet, which listed the classes that the school provided. We spent many a hot day pacing the streets of the city in the company of Alfred, a huge young Armenian, distributing these cards to all and sundry. The other device was a pair of transfers reading Push and Pull alongside the essential Nejad message. These were to stick on swinging doors and the distribution of them was an interesting exercise in that it put us in contact with people all over the city. John and I toured separately on these escapades however, and it began to divide our lives more than hitherto.

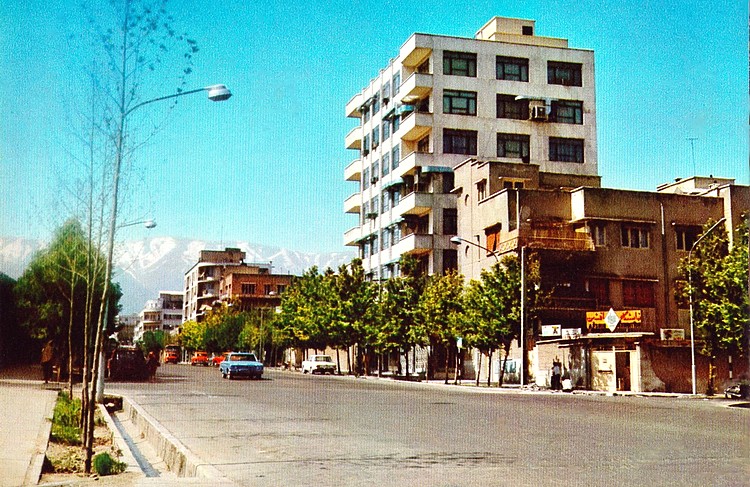

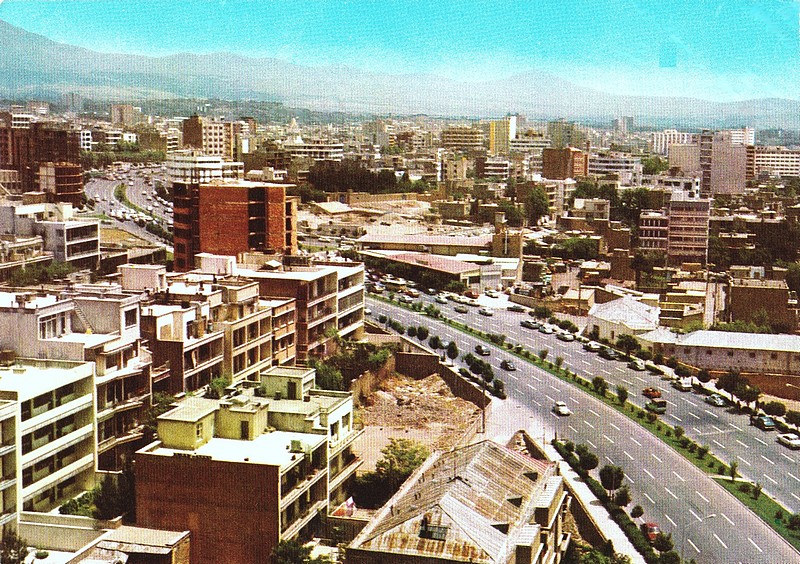

Postcard of Sepahbod Zahedi Street (now renamed Qarani Street), Tehran, looking up north towards the mountains, probably taken in the late 1960s. The jube rainwater gulley is visible at bottom left.

The weather was now becoming hotter, into the mid-90s Fahrenheit and, before we would depart, it was to rise further to a high of 112 degrees. It was a bearable heat but we were grateful for the air-conditioning units, water-coolers and showers at the school, and the trees, pools and fountains that were so common around the city. In the mornings it would be over 70 degrees by 7 o'clock and we found it impossible to stay in bed, being so exposed on our roof top. Undoubtedly the climate had stabilized and was now utterly predictable, so Nejad's promise that it wouldn't rain on our roof until October seemed accurate. This was certainly different from early May when we had experienced those sudden downpours, and the occasional freak winds that swept in from the desert on quiet warm evenings and devastated the Gol-e-Sahra campsite with clouds of sand and dust in less than five minutes. Our only real discomfort was when the temperature inside the van shot up if we had to stop. Waiting for the traffic lights to turn green was a painful experience.

It was not long before we found we were showing a profit. The cost of living for us was negligible and our entertainments always seems to be at someone else's expense. On the whole prices were low, but so were local standards. Imported goods might cost up to twice the European price, so the key to economy was to buy local produce.

I had dragged out my suit again for the new job but it was wearing through on one knee. I found a tailor in Sepah Avenue who said he could do the repair and a day or so later he charged me around 75 pence for a very good job. I showed the staff at the school what he had done, but they got quite agitated about the price and said I had been robbed. Amir Mehrdadian (another Armenian name) led me back to the shop and proceeded to pour abuse on the poor tailor who fought back by pleading that he had a business to maintain, many children to feed, and so on. Later Amir told me that the repair had actually been done very well, so perhaps it was a fair price after all.

Amir was the deputy headmaster and his English was pretty good. He always seemed glad to have one of us sit in during his classes, though his manner was embarrassingly effeminate and his question and answer sessions with us became rather too personal at times. We had to be careful how we phrased our comments, as the national pride could easily be upset by wrong answers to questions such as "Do you prefer England or Iran?", "Do you like the Shah?" or "Are Persian girls prettier than English girls?".

Our best friends at the school were the domestic staff - headed by Reza, Nejad's brother - and a team of general assistants led by old Mr Sabeh, master of the tea urn. In retrospect I would say that Reza possessed the finest qualities we came across in any of the Iranians we knew well. He was quiet, conscientious, unpretentious and honest, leading his small crew with diplomacy and wisdom. Though he didn't have his brother's education he had also escaped the ruthless ambition and social climbing that we were beginning to find were characteristic of Nejad.

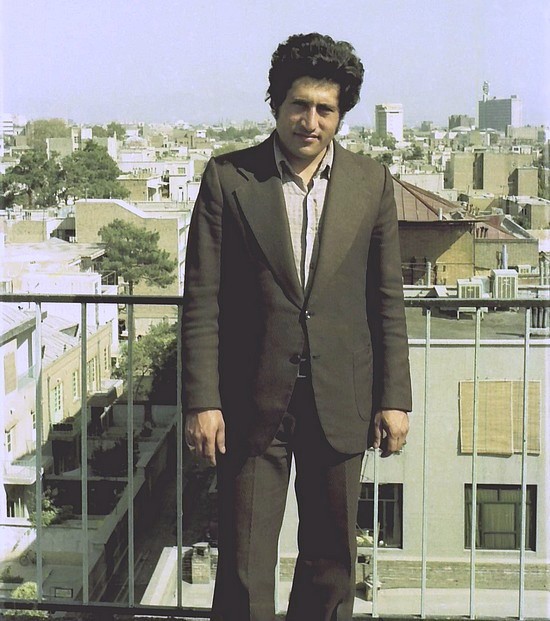

Reza, Nejad's brother, on the roof of the Nejad English School, Pahlavi Avenue.

One of the boys, Hamid, who was another effeminate type with ambiguous motivations, paid considerable attention to John, watching him at work for hours on end. Eventually John agreed to go home and have lunch with him one day, which turned out to be a straightforwardly hospitable gesture but led to an unusual journey back to the school. When they boarded the bus to return, it soon became obvious that the driver was drunk. He took the passengers for a hair-raising mystery tour at great speed and, having left his route completely, began to sing. The passengers joined in and decided to enjoy the unexpected diversion, eventually persuading the driver to stop at a tea shop where everyone disembarked for refreshments. John and Hamid arrived somewhat late at the school with an excuse that would have been barely credible in London.

Beside normal teaching duties at the school I was later recruited to hold conversation classes with Nejad's three daughters (who turned out to be excellent scholars) and was also given some outside students. One was a wealthy banker who lived in the north and already had a good command of the language. We would read English newspapers and discuss current affairs while I corrected minor errors in his grammar or pronunciation, but my greatest challenge was when Nejad gave me full responsibility for teaching someone the language from scratch. My victim was a businessman in Shahreza Avenue who took the lessons in his office during the lunch hour. We did pretty well and, with the aid of a specially prepared illustrated book, he made surprising progress under the circumstances. This outside teaching made about £1.25 per hour, so I was delighted to compile a busy timetable of such students and spent the days touring the city on my rounds like a district nurse.

Once again this helped to improve my Farsi, and both John and I were beginning to get a substantial grip on the language. Farsi was an anomaly in all directions. Iranians called it Indo-European and it certainly bore a close resemblance to the Indian languages, though it was written in Arabic script and used many Arabic words and expressions. An Iranian therefore could read Arabic but wouldn't understand it (unless they spoke Arabic) whereas a Turk, whose language was more closely related to Farsi, might understand some of the speech but wouldn't be able to read the script. (Pre-Ataturk Turkish in Arabic script might be interpreted by scholars, but presumably not by the general population as the Turks couldn't read it and the Arabs couldn't understand it.) Like Arabic, Farsi was written from right to left, except numbers which went from left to right, and books and newspapers started at the back.

Typical beautiful Islamic architecture; a mosque in the Tehran bazaar.

There were many hurdles for the English person learning Farsi including the tradition of arranging the script in patterns and aesthetically attractive designs, which destroyed the arrangement of the words for the basic student. Letters could take many different shapes to make words look better, and they varied according to their position within the word, while most vowels were left out altogether - you had to guess what was supposed to go into the blanks! Meanwhile some letters produced pronunciation difficulties, like the letter gaf which was a kind of subdued gargle, and ain which was never pronounced at all.

However the reverse applied, because Iranians had similar difficulties learning English and, for instance, really struggled to pronounce th or er as in mother, the result being something like mozzair. Arabs had the same problem. Curiously they found it hard to start a word with the letter S and tended to put a vowel sound in front of it, producing such words as e-school or e-sometimes. They also often confused the letters V and W and might reverse them, leading to our favourite expression "Wery Vell" by which we identified the Persians.

Despite the intricate yet rigid rules of Arabic spelling we found that, when the Persians wrote something in English, spelling was a minor consideration. There was a neon sign over a school in Ferdowsi Square advertising classes in ELECTERICITY, FILLING AND SECRETERIEL. One would have thought that, before investing in an expensive sign, the accuracy would have been checked; but not necessarily in Iran.

The English were also behaving in a typical fashion. A garden party was to be held in the grounds of the British Embassy on 13 June to celebrate the Queen's birthday, and everyone would be there. We were invited but declined the offer. However we did drop into the Embassy to inquire whether we could vote in the general election due in Britain on the 18th. Unfortunately we were too late to submit a postal vote, but the Embassy official said "Anyway we all know who's going to win, don't we?" Actually we didn't because we were several months out of touch, but we smiled, nodded and left. Subsequently we learned that the election result had caught everyone by surprise (Harold Wilson out, Edward Heath in) so it seemed that our Embassy staff were as ill-informed as we were.

Life on the roof was relaxed and pleasant. We were seldom there during the day when heat built up inside the building, straining to escape up the stairs and out into the open air. We only lived there at night, when we would open the door and release the pressure. A completely new world came into being on the rooftops of Tehran when the sun went down. We weren't the only ones living out under the stars and you could hear other people talking, laughing or playing music, echoing across the city. Tehran went to bed fairly early, and by 9 o'clock many of the families who had eaten their evening meals on other nearby rooftops had taken their washing lines in and settled down. But traffic could still be heard in distant Pahlavi and Sepah, and the occasional hooter or broken exhaust pipe echoed through the streets. I was interested to learn that, during the nation's Green Revolution in 2009 protesters (having been driven from the streets) used rootftops to send messages, call friends, chant slogans and voice dissent. Knowing how effectively sounds travelled through the night air in this way, I can quite imagine how eerie and moving it would have been to experience that.

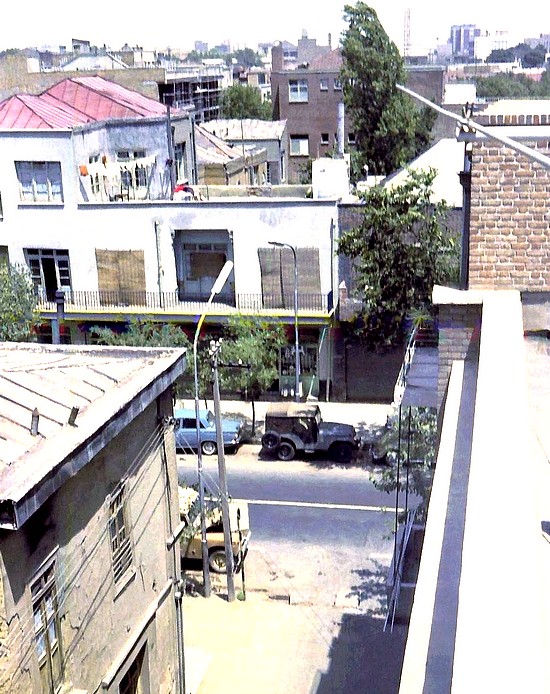

View from our rooftop home into the street. The Armenian garage is down on the right by the Jeep.

The overall mood at night was set by the warm, still air, the moonlit mountains to the north and a dome of brilliant starlight stretching out over the desert to the south. Down in our side street the night shift took over. The shutters were pulled down on most of the shops, but a bare light bulb swung from the ceiling of the little tea shop where pimps and various other dubious characters hung out. One small store remained open selling cigarettes, bottles of chocolate milk (sheer-coco, which we adored), biscuits, sweets and yoghurt, and over the road an Armenian family who ran a little garage sat on chairs on the sidewalk watching the world go by. Men dragged their beds out onto the street so that they could awake under the trees, rather than suffer the stifling heat indoors.

We had one light on the roof, sticking out of the wall over the door. It was not long before a lizard adopted this as his night-time home and he would regularly appear as soon as the light was switched on, glued to the wall by some mysterious ability. We welcomed his presence as he dined on the insects that gathered around the bulb. Occasionally we entertained guests on the roof. We made friends with the Armenians at the garage and the oldest of the five brothers in the family often visited us. He spoke recognisable English and his most valued possession was a Concise Oxford Dictionary which he had bought cheaply because it had thirty pages missing. One day he told us that his youngest brother was shortly to have a birthday and asked us if we could think of a cheap suitable present. We suggested he should buy Zebedee the bike, and at £1.50 he felt he'd got a bargain. Some days later we assembled the machine and the presentation was made. Thereafter the boy could be seen riding up and down the street, changing the three gears and proudly ringing the bell, the envy of all his friends.

Our rooftop home (photo taken while we weren't living there!)

We also made friends with two American girls that John had met at the campsite. They were travelling to South Africa via the Far East, Middle East and Europe in a blue Volkswagen Beetle and had brought, incredibly, two Alsatian dogs. We warned them that quarantine difficulties awaited them, but they had got as far as Tehran successfully and were determined that the dogs should accompany them for the rest of the journey. We invited them to the roof and had a delightful but simple evening singing songs and playing records, crowned with a luxurious cherry cake which we had bought in their honour. They told us that our music was good enough to perform professionally, which worked wonders for the ego. Some days later they told us that they were having problems with their visas and, when we drove out to the campsite one evening to see them, they had left without trace. This was probably just as well since the Alsatians were never quite sure about John.

With Michael and Sue, Wolfgang and now the girls gone, we began to realise that Tehran was not so much a place that people went to, it was more a caravanserai on the trail, as it had been for centuries. Perhaps it was time for us to move on. We had enjoyed the nomadic outward journey and found the new stability a bit limiting but, at the same time we had serious doubts about the wisdom of taking Dougal much further from home since his mechanical life seemed to be fast running out. On the other hand we had made a profit thus far and could afford another stage on the journey if necessary.

Valiand Square (now renamed Valiasr and extensively rebuilt) in north Tehran where Elizabeth Boulevard met Pahlavi Avenue. All orange cars were taxis and the one in this picture is an IranNational 'Peykan', the licence-built Hillman Hunter.

We thought of going south to Isfahan or Shiraz but the RAC guide said that the road was corrugated which deterred us, and besides we were reluctant to give up our jobs until we were quite sure of a constructive plan. Our answer came in the form of a letter accompanied by a tape reel that we picked up from the Poste Restante from two friends in England, Martin Giddey and Dave Calderwood. It seemed that they were preparing to come out and join us, driving overland in Dave's Mini. We therefore decided to stay put, and constructed a taped reply advising them of our intentions and giving them a few tips for their journey.

Now some musical notes; The reel-to-reel tape they sent was sheer magic. On it were three complete music albums and various individual tracks, mostly new to us. The first album was Simon and Garfunkel's Bridge over Troubled Water, which was top of the album charts back home in England and brought us great joy. The second was Led Zeppelin 2 (their finest creation in my humble opinion) which had been recorded on the tape in the wrong order - i.e. side two first. Since we played it in that order many, many times, we assumed that this was the correct order and it always seemed wrong thereafter when we heard it played correctly! However it appealed to the bluesy, heavy metal component of our musical taste (Jimmy Page certainly knew how to play blues guitar, as well as being a head-banging hero). This was a fabulous album which sounded astonishing played up on our roof under the stars.

The third album was Frank Zappa's second solo production Hot Rats. This caught us completely by surprise and made us laugh and listen in equal proportions. Frank's music was always very strange, but this was stranger than most. Since we didn't have much to listen to, Hot Rats got played a lot and we gradually got it and learned to love it, especially Captain Beefheart's weaselly vocals on Willie the Pimp. Then there were some Jefferson Airplane songs (I think from their Surrealistic Pillow album) but when it came to the final performance on the tape - King Crimson's track 21st Century Schizoid Man from In the Hall of the Crimson King - we were stunned. This was a real leap into the unknown, another dimension of music for us, and at first we didn't know what to make of it. But eventually it began to make sense and the bold ambition of the track led us to admire and appreciate it. I expect that almost everybody who might listen to that track now, if they managed to survive all 7 1/2 minutes, would probably vow never to experience it again, but it's etched in my memory; well done King Crimson and thanks to Martin and Dave for sending all those nuggets.

During the days that followed we played hosts to Johnny Eddy's band on our roof (who were stunned by the strains of Led Zeppelin and wanted to buy all our tapes and records), said goodbye to Jongy the guitarist who was finally off to join the army, and John found a huge split in the side of his guitar which was fixed by a Persian metalworker, who riveted part of a tin Coca-cola sign over the crack. In the street near our home I accidentally reversed Dougal into the 1ube and John backed him into a concrete post under the guidance of a helpful passer-by. Meanwhile fate was gradually piecing together a string of events that was to upset everything.

It all began when Nejad employed a beautiful 15 year-old dusky maiden as a receptionist. She couldn't type or speak English at all, but she sang like a bird. Her name was Azita and, more than anything in the world she wanted to be a professional singer, but her parents were against it so they appealed to Nejad to employ her and give her some secretarial training; and then the intrigue began. The Inspector of Schools was shortly to pay a visit to the Nejad School and it was apparently a tradition that, to ensure that he turned a blind eye in certain directions, there would be a huge party and he would be provided with a desirable female escort. Azita was the lamb for the slaughter, and she didn't know it.

This awful photo of Nejad English School staff members was rescued (barely) from the roll of film that got damaged, but it's the best I could achieve. From left to right are Hamid, John, Azita, Shahin the shorthand teacher and Reza.

During school break-times shy Azita would sometimes sing Persian songs in the staff room accompanied by Amir Mehrdadian on the flute, and we were struck by the beauty and purity of her voice. Gradually, inevitably, John fell for her, which threw the first spanner in the works. Certainly he could be forgiven for being captured by her classic beauty, although Nejad didn't see it that way and put the pressure on John immediately by protesting that she was too young and it was bad for the image of the school; but we knew the truth by then.

We were surprised to discover that Mrs Nejad was in on it too. John knew it was a losing battle but kept trying because he was stubborn in the face of such adversity, as Bali-Bali had discovered, but the message was clear - he and Nejad were now at war. After a few days the Inspector of Schools arrived and all was lost.

On the afternoon of the party John was working so I took Dougal round to Ferdowsi Square and had a drink in the White Cap Bar which served a passable Persian beer. A word about Persian beer; vodka and beer were produced locally and both were drinkable. The White Cap Bar was our usual watering hole and it was common to find British Embassy folk in there, so we could usually join someone for a chat. We mentioned on one occasion how much we missed real English ale and we were let into the secret that real Watneys Red Barrel was available in the English Bar downstairs in the Miramar Hotel. Of course we had to investigate this and, although Watneys Red Barrel was considered by connoisseurs to be the worst of all beers, it sounded like nectar to us two deprived Brits. A few days later we went to the Miramar Hotel and there, sitting on the bar was a genuine, big, brash, red, plastic, illuminated Watneys Red barrel beside a draught beer tap. We were salivating with anticipation as our pints were poured, but all hopes were dashed when we tasted what was clearly the same old Persian beer that was available everywhere else in town. It was true that the hotel had a Watneys Red Barrel, but they didn't have any Watneys beer in it.

Our favourite bar, the White Cap in Ferdowsi Square.

But let's return to the White Cap Bar; there I met a fellow from the British Embassy, we started chatting and a rather boozy session got underway, which he handled better than I did. Some three hours later I remembered the party and he offered to give me a lift to Nejad's house, where I arrived to find the celebrations in full swing. The entire affair had become a bacchanalian orgy with Azita and the Inspector in the thick of it. John was also there and, to my surprise, Nejad was smoking and distributing Tariokh - a kind of opium. I helped myself to some of the food but couldn't keep pace with the rest of the revellers.

John asked me if he could use the van, and I then remembered that it was still outside the White Cap Bar. To make things worse, I couldn't find the keys. My embassy chauffeur drove me back to the bar and, to my relief, Dougal was still there. Fortunately my companion spoke excellent Farsi and, after some very effective invective, the unwilling bartender admitted that I had left the keys on the bar, and they were retrieved.

Meanwhile back at the party the guests (including Nejad) had all left, many to take their respective partners away to more private places, leaving only John and Mrs Nejad. She was leaning out of the window crying, apparently suffering from a bout of homesickness. She then clung to John while reminiscing about London. He was just wondering which way to turn when he noticed Nejad's minibus draw up outside. He bolted from the flat, passed Nejad on the stairs without a word and, once down in the street, sat down against a wall to collect his thoughts, until a policeman moved him on.

When we got back to the roof we didn't care much for Tehran any more, and idly washed cockroaches over the parapet with buckets of water. It was a new method we had devised for clearing the swarms of huge crimson beetles that slept in the heat of our toilet during the day, waking up at dusk to rush out onto the roof when we opened the door and switched on the light. Having failed to reduce the swarm by trying to swat them into the sky with sticks one by one, we had come up with the idea of filling buckets with water when we went out in the morning, then using them to swill the creatures out through the gaps in the parapet wall designed to let rainwater out. But on this occasion there was a muffled cry from a balcony two stories down. Some poor fellow resting on a camp bed had just been anointed with a couple of buckets of water and several dozen cockroaches.

We were not surprised to find next day that a complaint had been made, not only about cockroaches but also regarding loud music on the night of the cherry cake, and Nejad demanded that we vacate the roof. John was not sorry. He had always hated doing the advertising jobs and had recently been asked to erect a huge metal hoarding on the roof of the school while balancing precariously on the edge, which was practically the last straw for him. Before Nejad said a word we had already decided to go home.

Postcard picture of Karim Khan Zand Boulevard (which is still called that!), Tehran, looking north- east. Probably taken in the late 1960s.

But what of Azita? We didn't see her again but, in 1974 when I visited Tehran again (yes, I forgave the city and had to go back!) I asked the Nejads what had become of her. They were reluctant to say anything at first but, when I pressed the point and asked if she ever achieved her singing ambitions, Mrs Nejad said that Azita had become a professional escort. "We don't talk about it" she said, "It was her upbringing you know." Could that be true? Perhaps the Nejads didn't really know what had happened to her, but disliked her enough for some reason to say such things. It seemed likely that Nejad employed her with the Inspector in mind and I would like to think that she was unaware of what was expected of her, and her parents were equally so. Such things were not unknown; there were stories of English girls being employed as dancers in Iran and finding that the job entailed more than they bargained for. Tales of a similar nature were also coming out of North Africa, especially concerning European blondes, apparently a local delicacy. Anyway it was all a very distasteful business.

We spent the next day clearing up loose ends in the city, including a visit to an infamous low-rent hotel, the Amir Kabir, where some friends of ours from the US Peace Corps were staying. This spartan hostelry usually accommodated a good number of the passing, financially-challenged travellers and was therefore an endless source of fascinating tales. We gave our three friends a lift with all their gear to the bus station from where they were heading west. We were so overloaded with them and their luggage on this journey that I had to stand on the tow-bar while hanging onto the roof rack for dear life.

A glimpse of part of Tehran's bus station. On the left is a classic early 1960s Mercedes O321H, while two Mercedes O302 coaches are on the right, locally-built by IranNational and probably dating from around 1970.

We then returned to the roof and moved all our gear back down the ten flights of stairs to Dougal, John took some last pictures and then we locked up and returned the keys to Nejad. Once again we headed out towards the Gol-e-Sahra campsite. The road was fairly straight but narrow and cost us many a missed heartbeat, especially at night, largely due to the trucks. Persian trucks were magnificent monsters built on solid Mack, Ford or Mercedes chassis with coach-painted slatted wooden bodywork. Many were assembled by IranNational and the rest by private concerns like the Khawar Truck Factory just near the campsite. However it was their lighting that made them so hazardous. Each driver adorned his vehicle with signs and transfers, coloured lights and hooters, even lace curtains. The result at night was a moving Christmas tree. If the vehicle in the distance was displaying one blue light and three orange ones it was difficult to decide whether it was definitely a vehicle, let alone which way it was going.

To make matters worse these trucks seemed to have no dipping facility on their headlights so the Persians had invented (or adopted) an alternative system which worked like this; you and I are in two vehicles approaching each other on an unlit road and we both have our headlamps full on. Soon your headlamps start to dazzle my view of the road so I turn my lights completely off for around 2 to 4 seconds. When I put them back on (so I can see where I'm going), you switch yours off for the same period of time. We maintain this rhythm, alternately either having an illuminated road to ourselves or being completely blind, until we pass each other. Unfortunately the lights on Dougal were very dim and no-one took us seriously, so they would just leave their lamps fully on and we had to fend for ourselves. One night near the camp we were totally blinded by a truck while we were each doing at least 40 MPH, so John gritted his teeth and hung on in the hope that we would maintain a straight line. The truck bent our offside wing mirror as it passed.

A Mack truck and its proud owner near Tabriz. This model was common and seems to have been uniquely Persian, probably built from wartime or 1950s Mack chassis components with a locally-made cab, possibly by IranNational.

We made some new friends at the camp, including a charming Canadian couple, Ken and Ingrid McLeod, and an odd English freak who called himself Nick the Gem. He had hitched from India and, on the way, had bought an unusual and unwieldy 16-stringed Afghan instrument, which he called a Rubbub (otherwise known as a Rabab, Rebab, Rubab, Robab, Rehbab and probably plenty of other things), for 7 Dollars. He couldn't play it and neither could I. Nick reminded me of an elf, but was permanently bright and cheerful, which he would need to be if he intended to carry the bulky rubbub all the way back to England; but he was certainly no novice at the travelling game.

Our last day in Tehran was spent in frantic activity. In the morning John drove into the city saying farewell to all and sundry, taking a hurried set of photographs and posting the tape to Martin and Dave (all the information on the tape about our intentions was now incorrect, of course) while I stayed at the site to wash our clothes and kitchen hardware. In the afternoon we positioned Dougal over an inspection pit next to the camp and, while John did a thorough overhaul, I hosed down and washed the bodywork, windows and cab interior so that we both got very wet. Then we turned everything out of the van and had a spring clean, as we had done at St Tropez, packing it all back neatly and re-lashing the roof rack. Finally we both had a shower and filled up the water tank. Somewhat shattered we spent the evening with Ken and Ingrid but went to bed early in preparation for another long day to follow.

Tehran had been good to us on the whole but still left us confused. On the one hand there was colour, sunshine and cloudless splendour while, on the other was dust, disease, poverty and suffocating heat. We failed in a way because some of the initiation ceremonies were too distasteful and we didn't adapt adequately - which I suppose we might have done if we'd stayed longer. At first we thought that Mrs Nejad had settled in and gone native but she clearly hadn't, so it obviously wasn't an easy transition for the English. But equally we learned a lot and had many fine memories to take away with us, largely due to the cheerful and varied characters that made up the melting pot of the Iranian population and the people who were passing through.

We got off to an early start with a couple of fried eggs at a little cafe on the Saveh Road. Unfortunately Iranians always made a mess of fried eggs so, as usual, we cooked them ourselves. Our last view of Tehran, like our first, was at Mehrabad Airport, where we watched the movement of two Iran Air Boeing 727s, a KLM Douglas DC-8 and an ancient US Air Force Douglas C-47 Skytrain. They were just starting to extend the passenger terminal and four years later I was able to see painters putting finishing touches to the enlarged concourse. About a month after the job was complete the roof collapsed killing 70 people. Apparently heavy snow impeded rescue attempts and was probably responsible for overloading the roof in the first place. I always find it hard to imagine Tehran under heavy snow, but the temperature sometimes went down in January to an unbelievable 30 degrees Fahrenheit below freezing.

The Tehran Airport terminal building before the roof collapsed.

Finally we got moving on the road back to Europe and home and I must admit that a strange feeling came over me as the miles rolled by. Although we certainly wanted to get back to England, partly because John wasn't getting any dates and also because I was losing confidence in Dougal, there was no doubt in my mind that travelling had opened up a whole new viewpoint on life for me, and I would have itchy feet for the rest of my days. I knew that I hadn't finished with Iran and was leaving too early, but it didn't seem too important because I was certain that I would soon be back. This was not a vow that I made to myself, it was merely a piece of information that was as obvious and inevitable to me as the passing of time. John, however, had had enough. He was glad to have Tehran behind him, would be still happier once on English soil, and was never to have any great inclination to travel in that fashion again.

We stopped in Zanjan for a cup of tea and a last meal of ob ghousht at around mid-day and, sitting there in the shop to our surprise, was the soldier with his jeep, but without his sheep. He seemed much more pleased to see us than we were to see him, but he bought us cups of tea and chattered incessantly until we left.

Out in wilder country towards Miyaneh we met one of many English expeditions on their outward journeys. This bunch were apparently the Oxford University Ecological Expedition to Nepal, though we had our doubts about the motives of anyone heading in that direction; more likely it was the Oxford University Hashish-Hunting Team but the two huge ex-Army radio vans in which the group were travelling impressed us, although their fuel consumption must have been pretty high. The vans certainly looked rugged enough to cope with anything. The group of eight or ten lads boosted their ecological credibility when one of them became very excited about a circling dot in the sky about a quarter of a mile from the road, and identified it as an Egyptian vulture. No-one dared argue.

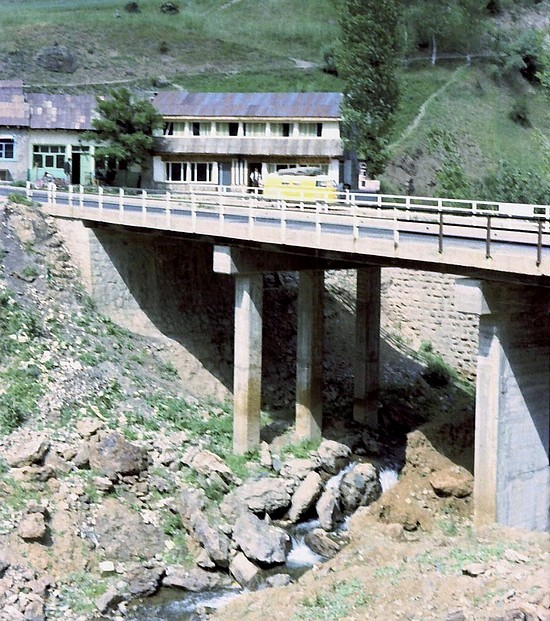

Broken bridge by the road near Miyaneh, western Iran.

Nearby we came across a collapsed bridge over a mere trickle of a stream. On our first journey along this way John had driven Dougal up onto the bridge to the very edge of the broken part and I had taken a photograph of it all. Since we suspected that the film was now spoiled, I suggested that we re-enact the episode. However on closer inspection of the bridge we found so much cracked and crumbling masonry that John refused to risk it, so I took a picture of the bridge by itself. If you are a builder of desert bridges, the lesson seems to be that the structure may straddle a very small stream or nothing at all in the summer but, if you don't make it of great width and strength, it will be knocked ever by a raging torrent in the winter.

In the early evening we reached Tabriz which felt colder than ever. After driving to the familiar campsite in the hills behind the city we made a quick meal and went to bed shivering. When we awoke it was crisp and bracing, and we got away so early that even the Persians were still yawning. On the western outskirts of the city a mass of trucks and coaches of all shapes and sizes were lining up beside the road while their drivers washed windscreens and loaded roof racks. Potential passengers staggered up the road humping crates or bulging sacks on their backs.

Regional transport ranged from battered Transit vans or decorated Mack lorries to the fleet of blue Tabriz Now (New Tabriz) long-distance Mercedes coaches. The one hundred or more vehicles that stood in the chilly morning air would probably be gone by 8 o'clock, the big ones bound for Tehran, Isfahan, Kerman, even Turkey and Afghanistan, while the little local services would be battling up into the mountains or to isolated settlements in the desert. All over the country, travel started early because of the distances involved, and in some towns camels and donkeys were still in use.

We reached Maku for an early lunch and then toured the shops buying sweets, biscuits and other bits and pieces with our remaining few Persian Rials before heading towards the frontier for the last time. The border was negotiated in record time and we were surprised when nobody on the Turkish side mentioned insurance. A few miles down the road we stopped to chat to the occupants of a Hillman Imp van which was going the other way. They were heading for Australia via Bombay and asked us what the Iranian frontier was like. We warned them that it could take a while but, provided their documents were in order, there should be no problem. We then discovered that they had neither a Carnet de Passage nor a sea ticket from Bombay. We had learned from the unfortunate experiences of other travellers that, without a Carnet, one could get no further than the border we had just passed, and that there was a six-month waiting list for the Bombay boat, it was very expensive, and the booking should be made from London.

In so many cases the Bombay boat turned out to be an expedition's downfall. A group would arrive at the dock, find that they could neither afford the fare nor the six-month wait (let alone both) and accordingly would head back to countries like Iran where second-hand car values were highest. An old Bedford van with a Carnet value of say £200 might fetch £400 in Tehran or Kabul. The van would be sold, without paying import duty, and a nice profit made which would enable the group to return home by rail or hitch-hiking in comfort.

It was for this reason that Iran finally clamped down on the Carnet system by demanding a deposit of between 200% and 500% of the value of the vehicle when new, which meant that the deposit required for that old Bedford van could be from £2,000 to £4,000. This put the cost more in line with the sale price plus the import duty payable if the vehicle had been sold legally. Naturally no-one would pay such a figure for an old Bedford van, the sale would not take place and the loophole was closed. Unfortunately, from around 1976, this effectively closed the Asian Highway as well for those travelling on a shoestring, who would find that half of the cost of any expedition beyond Turkey had to be left idle in London as a surety so that the RAC or AA would issue the traveller with a Carnet.

No doubt there were ways round the problem - the travelling fraternity was usually pretty quick to find a means of saving money. At any rate we told the boys in the Hillman Imp what we had been informed and wished them luck. There are so many variables and corruptibles in these places that most things are possible with a little ingenuity and I hope they made it all right. Perhaps those who failed just didn't try hard enough.

We made a rapid stop in Taslicay to greet Dr Hikmet and take another photograph to replace those we thought we had lost then, with darkness hot on our heels, we dashed into Agri and settled at a petrol station as night fell. Agri was typical of Turkish villages in the area and had a special charm by night when the menfolk sat around boilers and stoves in the tea shops playing games and talking quietly in the greenish glare of hissing paraffin lamps. The Turks didn't seem to have the bright exterior of the Iranians, but wore rather grim and sinister expressions which only served to reinforce the air of mystery in the more remote districts, though we were always relieved to discover that, beneath the surly exterior, lay a gentle and generous personality.

Dr Hikmet, his wife and family at the hospital in Taslicay, Turkey.

Another early start and some hard driving across the gently ascending terrain, with the mountains visible in the distance, brought us by lunchtime to the sign which read ERZURUM 1860m NUFUS 105,317 which referred to the altitude (6,200 feet) and population of the city. For some reason the Turks felt that a visitor always needed to know the nufus of each town or village. After lunch in Erzurum, selected by walking into the restaurant kitchen and pointing to the most appealing saucepans, and a chat with an American couple in the usual Volkswagen caravan who were seeking ancient monuments (in which the area abounds) we headed up into real mountain country again.

There was a magical quality to the mountains of Eastern Turkey and I would have welcomed the chance to explore them further, even if only to take the alternative route that runs directly from Erzurum to Ankara; but with Dougal in an uncertain condition we felt it wise to stick to the route we knew. Although the temperature in the area had risen since we had first made the journey (just as well since our heater was no longer working) still the weather was, at best, bright but cold and, at worst, pouring with rain; yet this only served to reinforce the lesson that weather, either good or bad, was an essential part of the character of a landscape. One never knew what was around the next bend, especially since it seemed to vary from journey to journey. I had taken a photograph of John and Wolfgang on a rope bridge across a gorge to an island, but it was on the damaged film of course and I guessed (correctly) that we had lost it, so we decided to take another - but never saw the bridge or the island again.

When we were climbing towards the Kopdagi Gecidi pass an old blind man, miles from the nearest settlement, heard the approach on our engine and came out of his derelict hut to beg by the roadside. Further on we saw some little animals beside the road that looked remarkably like Dolmus. Waiting silently outside their burrows and trying to grab them with our bare hands turned out to be rather fruitless however, so we left them in peace. At the top of the pass we stopped and switched off the engine to listen to the silence. The sense of wild remoteness was accentuated by an eagle circling lazily over an adjacent hill and we watched it wheeling and turning, struck speechless by the grand panorama.

Near Bayburt in the late afternoon a magnificent military DUKW amphibian landing craft rumbled past us, its Rolls-Royce engine growling healthily with the heavy-treaded tyres singing their way along the tarmac. An extraordinary variety of vehicles were heading out towards the Far East and Australia ranging from double-deck buses and traction engines to Jeeps and bicycles, some of them barely roadworthy. Somewhere down the trail there must be a very unusual motor graveyard.