The Classic British Isles Buses Website

An overland trip from England to Iran in 1970

Story by Richard Gilbert.

Part Two - Istanbul to Tehran

Last updated 4 September 2024

Email Events diary Past events list Classified adverts Classic U.K. Buses Classic Irish Buses Classic Manx Buses

The Blue Mosque, Istanbul

In the evening we put Dougal on a ferry boat and sailed across the Bosphorus to explore the Asian quarter. The ferry was quite an institution; there were six or seven different routes across the strait plied by car ferries moving five million vehicles each year, and 1,000-seat passenger ferries. The journey took about fifteen minutes through grubby, polluted water, but the wait to board the ship could easily be two or three hours, or even several days in bad weather.

The first settlements were established on the Asian side, but a Byzantine move in 700 BC established a community on the other side of the water, apparently on the advice of the Oracle at Delphi. Byzantium became Constantinople in 324 AD and began to flourish, soon becoming the most beautiful and wealthy city in the world. Ottoman Turks took the city in the 15th century after 150 years under the Crusaders, and so it remained until the Turkish republic came into being in 1923.

Having been the capital of three empires, Istanbul inherited legacies of each phase in its history, but the Asian quarter seemed to be devoid of the really early buildings, though we did find wooden mansions and decaying houses - some the former homes of wealthy traders - nearly 200 years old. However, these soon melted into farmland, and we found Uskudar almost rural in character. The really outstanding feature was the grim fortress of the Selimiye Barracks, headquarters of the Turkish Army and prison, whose forbidding walls stood like a workhouse above the ferry station. We waited nearly two hours to catch the boat back, beset by vendors of everything imaginable from balloons to jewellery.

In the morning, the lady at the Iranian Embassy announced that they required 24 hours to issue a visa. There were two available, a transit visa valid for 15 days or a multiple-entry visa valid for three months. We explained that we wanted to apply for work and residence permits on our arrival and she said that, in this case, there was no difference between the two, so we took the fifteen-day visas because they were cheaper. Our departure was thus delayed another day and we debated what to do with the time. Wolfgang visited the local students' centre where he acquired a fake student card which he felt might reduce his travel costs by air or train, and this turned out to be a very sound investment. Then he went off to take a six-hour sightseeing boat trip for 7p, and we went to the Pudding Shop.

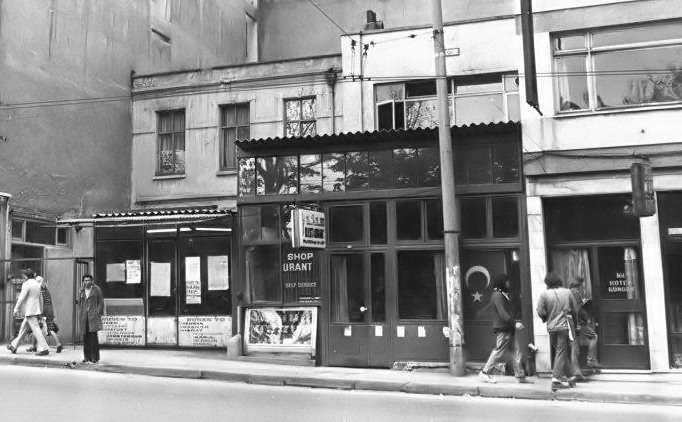

The Lale Restaurant, known to everyone as the Pudding Shop, the no. 1 meeting place in Istanbul.

Overlooking the Blue Mosque, the Pudding Shop was a cafe (named after its famous rice puddings, but officially called the Lale Restaurant) which had become the place where young people of all nationalities gathered when passing through the city. A jolly attendant, proudly sporting a peaked cap, guarded the car park opposite which always contained an international selection of travellers' vehicles - English, Dutch, American, French, Canadian, German and Swedish being the most common. By the door of the Pudding Shop was a notice board with messages in many languages, such as "Driving west? I need a lift to Vienna", "Anyone want to buy a tent?" or "Hans, I am back in Istanbul and staying at the Youth Hostel." Inside were the travellers, exchanging advice and information while hitch-hikers joined up with new parties and drivers formed small convoys. On that particular day we sat upstairs looking out at the Blue Mosque through a persistent drizzle in the company of an American girl named Linda who was staying at a hostel west of the city.

After a while Wolfgang returned, having changed his mind about the boat trip in view of the weather, and we all decided to visit the Topkapi Museum, a restored Ottoman palace of vast extravagance. Exhibits ranged from a sultan's opulent tent to a 2 inch, 86 carat diamond. The harem of 400 rooms was not yet open to the public, but an equally lavish sight was the view from the colonnades and balconies across the roofs, domes and minarets which sprawled over the old city and tumbled into the waters of the Golden Horn.

In the afternoon we ventured into the vast covered Grand Bazaar - 50 acres of bubbling activity incorporating 4,000 shops in more than 60 little lanes. Literally anything could be bought or sold in the bazaar but the speciality was jewellery, and most shops had a dazzling display of gold trinkets tinted with copper, giving them a typical reddish appearance. Carpets, sheepskin, tin and copperware were other specialities and the shopkeepers, often with enough of three or four languages to their credit, implored all who passed to take a closer look at their wares. As soon as a customer showed interest they were served tea, either on a tray from one of the many tea shops, or by a wandering tea seller carrying his huge urn on his back.

The bazaar, dating back to the 11th century, was a huge maze and it was very easy to get lost. Fortunately we managed to keep track of our wanderings. John sold a suit that he had brought from England for that precise purpose - and for what he felt to be a very good price - and then we drifted through the endless crowds, just browsing. Incredible though it sounds, nearly half a million people passed through the bazaar every day, which tended to make life very easy for thieves and pickpockets, helping to make it a centre for crime and intrigue, as it probably had been for centuries. John was uninspired by the Topkapi Museum but he really enjoyed visiting the bazaar.

A fraction of the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul.

There is no doubt that the bazaar in Istanbul was very much geared towards the tourist, whereas the one we were later to see in Tehran was more traditional and local in function, a surprising fact since the one in Istanbul outdated Tehran's by over 400 years. For example 80% of the bubble pipes made in Turkey were sold abroad or to tourists, and a lot of the locally-made jewellery, in what appeared to be a traditional style, would not appeal to a Turk at all, being too old fashioned. The only purchase we made was a baby grey mountain squirrel which cost us 50p. We named him Dolmus (pronounced Dol-moosh) after the local taxis (mus is apparently the Turkish word for a rat, mouse or squirrel) and he retired into my pocket to sleep, obviously another Wolfgang. We had a cup of tea, left the bazaar and took Linda back to her hostel. Then in preparation for a busy day to follow we had an early night.

At last the day came when we were to leave for Iran. We estimated that the journey to Tehran would take about eight or nine days but we decided to spend a few days in Tabriz to see whether it was possible to work there. Other than that, it was certainly going to be a period of hard driving.

It was Wolfgang's birthday so we bought him a large sticky cake, one of his weaknesses. He gratefully ate most of it in the Pudding Shop and then returned to bed. We collected our visas, boarded the ferry and sailed out of Europe at one o'clock. Then followed an afternoon of difficult progress in incessant rain. Eventually we halted at Bolu, a village only 150 miles from Istanbul, and spent the night on the forecourt of a 24-hour petrol station (fuel prices, by the way, were about one third of the UK rate). Of all the places we visited, Turkey took the prize for the largest number of inquisitive onlookers. They crowded round the van wherever we stopped, and not just children. The adults stared at us while the children were more likely to speak. Often they would ask "Are you English?" but, when you replied, they couldn't say any more, although one did manage "Bobby Charlton, very good man!". Still they were non-violent (mostly) and we eventually got used to it.

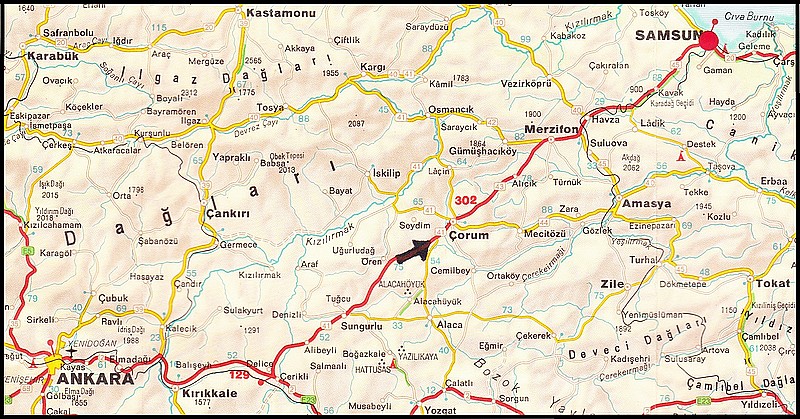

It could be hard to work out where you were when you woke up. The view was often a complete surprise when opening Dougal's door in the morning, particularly because we often arrived at our sleeping place in the dark. That morning, however, we opened our doors to a plain, ordinary petrol station just east of Bolu. So we filled up with petrol and set off at half- past eight, intending to drive to Samsun on the Black Sea coast by nightfall (by-passing the capital city of Ankara) which was a challenging 340 miles as the Turkish crow flies. Poor Dougal was suffering a bit at the time and the roads were getting steadily worse. A constant battering on uneven surfaces and several colossal bangs resulting from surprise bumps and pits must have put a great stress on the vehicle but all we could do was keep lubricating the faulty wheel bearing with the intention of undertaking an extensive overhaul in Tehran - if we ever got that far. A horrible grinding noise from the bearing as we neared Ankara reminded us that we should take care not to put any more strain on Dougal than necessary, especially with the difficult mountain roads of eastern Turkey ahead of us.

In the late afternoon, driving from Corum to Samsun, I noticed a certain reluctance on Dougal's part to maintain his usual speed. I mentioned this to John so we pulled over to see if anything was visibly wrong with the engine. Grateful for the chance to stretch our legs we stepped out into the barren wilderness to take a look. Nothing was apparent but we became aware of voices shouting at us from a tent a few yards off the road. A fellow in an old jacket and the ubiquitous cloth cap was beckoning to us to join him for a cup of tea. We went over to his tent where he stood surrounded by women, children, dogs and donkeys. He had a little charcoal fire burning in front of his simple tent and a steaming teapot awaiting us. We took our shoes off as we sat on a blanket in front of the fire in the place of honour. The women handed us little glasses of tea (Chai), refilling them as they emptied, and we responded by plying our Turkish friend with an endless stream of cigarettes, which seemed to delight him.

Me and John receiving hospitality from a nomadic family (possibly Kurds) in northern Turkey. 17 April 1970. Wolfgang took the photo. The tent faces east.

We had absolutely no common language at all, so conversation was out, but a great feeling of hospitality and friendliness built up, while his children stared wide-eyed at us and his wives or daughters, or both, chattered incessantly in spite of occasional sharp words from the man of the family. He showed John his gun, a beautiful carved rifle with an engraved silver stock marked Paris. It looked very old and obviously hand-made and appeared to be his prize possession. We examined it with suitable admiration and then, after a partly successful attempt to describe where we were from and where we were going (Wolfgang became English to simplify matters) we got up to leave.

I had been racking my brains to think of a suitable gift for them, but then I remembered that I had brought a magic scribbling pad that would erase any writing on it by the action of a slide. I fetched this from the van and presented it solemnly to the eldest of the little boys, after a demonstration of its properties. Feeling that we had, in this way, at least made a gesture of our gratitude for the hospitality, we took our leave with many handshakes and farewells and set off once more for Samsun which we would be lucky to reach before dark. This was a fairly typical example of the friendliness of people we met in this part of the world. However that didn't always apply in the cities, so it's a shame that many visitors to Turkey never get beyond Istanbul or the southern coastal resorts, and thus carry away an unbalanced impression of the people. Dougal rolled into Samsun at half past seven, having covered 4,000 miles since leaving home. We parked for the night outside the local Volkswagen agency, as John felt it wise to have the van thoroughly inspected in the morning.

When Wolfgang and I awoke, John had already handed Dougal over to the Volkswagen mechanics who checked its lubrication and a lot more besides. They would accept next to no payment, which was convenient as we were rather short of Turkish money. We drove on down the coast a little to find a suitable spot for breakfast and chose a place on a ridge by the shore. However on leaving the road Dougal became stuck in the soft sand. After futile attempts to extract ourselves, we were joined by a bus-load of people and a Jeep. The people and the Jeep set to work to tow us out, but the Jeep bent its tow-bar and sank into the sand like us, while the people laughed. Then a Land-Rover arrived but he just got bogged down as well.

Stuck in the sand on the Black Sea coast, which is just beyond the dune on the right. Soon it got more complicated than this! 18 April 1970.

By this time we had gathered about twenty gabbling Turks all brimming with advice, some on the spot and some up on the road, all enjoying every minute. A truck stopped on the road and the driver discussed the problem, but he wasn't keen to try and help, and his vehicle wasn't very suitable anyway. Finally everyone shouted as a tractor drove by, and the driver brought it down off the road to assist us. After a couple of failures it was this tractor which eventually got us all back onto firm ground. Later, with everyone safely on the road and crowded round the van, we got out our guitars at their request and produced a quick rendering of "When the Saints go Marching in" which was received with mixed feelings but much goodwill. Then, since our friends wouldn't accept any reward except the song, we all went our separate ways, still not having had breakfast.

The rest of the day was spent driving uneventfully along the coast in rather dull weather, looking for a bank to change some more Turkish money and becoming unpleasantly familiar with the habit that a few Turkish children have of throwing stones at passing cars or begging for cigarettes. As night fell, and having covered just over 200 miles, we came to a small coastal town called Tirebolu and decided to stop for the night. We had a bit of shopping to do and the shops still seemed to be open. There was also time for a cup of tea so we found a crowded tea shop, sat at a table and awaited our refreshments.

Presently a group of men came over and one of them greeted us in English. Evidently he was the local English teacher and valued the opportunity to practice his ability, especially in front of his friends. Tea was no problem from this point - cups came thick and fast, and it was out of the question that we should pay for any of it. Before long, our table was surrounded by a sea of faces with everyone craning necks or standing on chairs to get a better look at their new hero talking to three strange foreigners in a language they understood. Conversation gradually became easier as his English warmed up, and at one point he asked what we were doing in Tirebolu. We said that first we wanted to buy some bread, then stay the night. Immediately a boy was sent out to fetch us the bread, and he returned rapidly with half of a gigantic loaf for which payment was once again impatiently waived aside.

Then our friend surprised us by advising us most emphatically not to spend the night in Tirebolu. He urged us to drive on and reach Trabzon instead, saying that Tirebolu was not a desirable town for us to sleep in, and that Trabzon would be much safer. We decided to take his advice, though not entirely sure what it was based on, so after more tea and conversation we rose to leave. Once again I felt some kind of gift was in order and gave him a copy of Shakespeare's Hamlet that (like every traveller, I'm sure) I happened to have in my cupboard. He seemed most grateful. So we drove on into the night and reached Trabzon an hour or so later.

Finding a place to park for the night presented a problem, and we cruised up and down the sea-front for a while in search of a suitable site. We used our tow-bar for the first time to help a Turk get his battered car started, and finally found a manned petrol station at the extreme eastern end of the town, on the road up into the mountains. It was practically the last building before the hills and provided us with a lit forecourt and a safe base until the morning. When we awoke and stepped out into a steady drizzle, we were surprised to find ourselves parked in a steep valley with a stream trickling over rocks behind the garage. Even in the rain it was a very picturesque situation and, once again, on our arrival in the dark the night before we had no idea what it actually looked like.

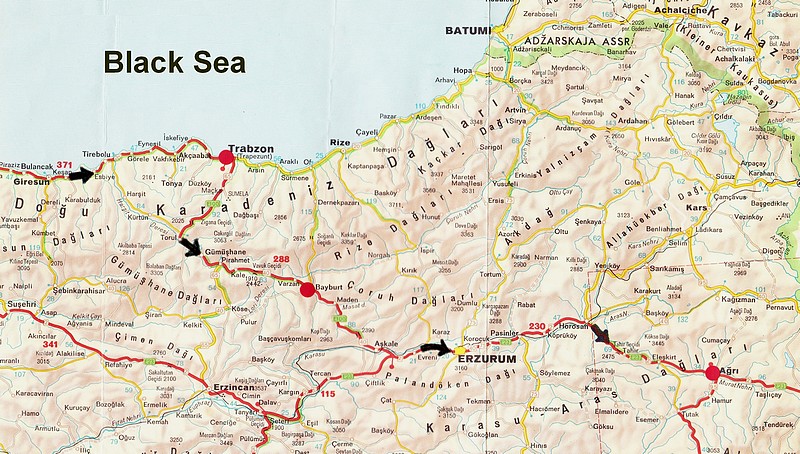

Dolmus the squirrel needed his nut supply replenished so we went into the town and bought him some almonds and food for ourselves. Then with a full tank of petrol and a satisfied squirrel we set off into the rain, knowing that the terrain would be difficult, but setting ourselves the modest target of reaching Erzurum that day, a distance of only 204 miles. The road climbed steadily upwards and away from the coast with habitation growing more scarce and traffic becoming increasingly rare.

By far the most interesting piece of the world we came across on our journey was the mountain road from Trabzon to the Persian border at Bazargan. Though we were to traverse this stretch four times, it was totally unpredictable and looked different every time, but it was really challenging. As we wound our way slowly up and up, mist gave way to cloud, then rain (soon becoming continuous) and finally snow. There were practically no straight sections of the rapidly deteriorating road - the rising, twisted land surface forcing the Asian Highway into monstrous contortions. For hours we didn't get out of second gear, and often could only use first.

The road up into the mountains from Trabzon. Wolfgang and John pose in the mist and drizzle. 19 April 1970.

The first pass we had to traverse was the Zigana Gecidi, reaching 6,644 feet above sea level at its lowest point. That point is only about 35 miles from Trabzon which is, of course, at sea level so this was a hard climb for Dougal with three people and all our junk on board. We were often in solid cloud, unable to see either the road ahead or the mountains around us. Other traffic on the road had virtually ceased, and this, with the enfolding fog, gave us a vivid sensation of isolation at times. The snow further obscured the visibility and lowered the temperature. The gravel track that the road had become was walled on either side by drifts up to six feet high, obviously left from the winter falls. Occasionally the cloud would clear for a few moments to reveal startling views down slopes and valleys that seemed to have no bottom. At half past three we reached the top of the pass where 2 or 3 houses, a store, a tea-shop and a police hut marked the spot. The whole lot was built on a U-bend in the road between two mountain slopes vanishing up into the mist. Visibility in the snow was now down to a few yards.

Nearing the top of the Zigana Gecidi Pass, steady snow and sub-zero temperatures. 19 April 1970.

We stopped for a cup of tea and kebabs, warming ourselves round a stove made out of an old oil drum. Then we got back into Dougal and began the long haul down the other side. Bad visibility and hairpin bends kept our speed to a minimum and, when we pulled into a spectacular little village called Kalkanli about six miles beyond the pass, we had only covered about 50 miles all day. The owner of the Hotel Kulis gave us some tea and chattered in German (which Wolfgang at least understood) and then we left him and set off into increasing darkness to arrive at Bayburt at around 7 o'clock, having abandoned any hope of reaching Erzurum that day.

Bayburt was a most surprising town. Though about 5,000 feet up in the mountains and nearly a day's drive from the nearest comparable town, it was quite well developed. Although sometimes totally cut off by snow for weeks, the people had thrived and were a most hospitable community. We considered it advisable, if not essential, to spend the night in towns or large villages, as the danger of marauders in the darkness was very real if one decided to sleep out on the mountain. We parked outside Bayburt police station, always the safest place, and went for a meal in the restaurant opposite. We didn't know what we wanted to eat when we walked in, and nobody had a common language, so a waiter took us into the kitchen to see all the various things being cooked. Each of us pointed to any of the pots that interested us, and he brought the meal out when it was ready. This easy menu system was common in the region for serving food to ignorant foreigners, and we became quite familiar with it. Meanwhile the food was good, and cheap!

After eating, we took a look at the town with its wide, long main street of small supermarkets, new office blocks and fashionable clothing shops. Wolfgang made contact with a Turkish coalman who had spent three years in Bremen building ships, so spoke excellent German. This earned us a free drink and more Turkish hospitality before we went to bed.

We were awakened by the early morning call of a bus driver who stood by his Transit van shouting "Trabzon, Trabzon, Trabzooon!" to assemble his passengers. First some shopping in the fresh mountain air and then it was time to depart for Erzurum. Unfortunately Dougal refused to start for some reason, so we recruited the inevitable crowd of inquisitive onlookers to give us a push.

The Kopdagi Gecidi Pass. 20 April 1970.

We were on our way by 8:15 and headed out along the narrow winding road towards the Kopdagi Gecidi pass, 7,841 feet up. Though higher, this turned out to be an easier pass to traverse than the Zigana and afforded remarkable views. The whole stretch from Trabzon was very spectacular and exciting but the passes were breathtaking. From the Kopdagi Pass the road went downhill more or less all the way to the border, right across the central Iranian plateau and into Afghanistan, making a welcome change from all the first-gear climbing of the mountains. We came down out of the snow and entered fairly level country with an average Turkish road surface. This helped us to maintain a good pace for that part of the world, and it began to look as though we would get well beyond Erzurum by nightfall.

Soon we entered what was surely the largest military zone I had ever seen. Everywhere there were soldiers and barracks, stores, parade grounds and exercise areas, vehicle parks and firing ranges. The surrounding hills had giant white numbers on them, along with the Turkish crescent and star motif. This zone covered an area around Erzurum with a diameter of about 50 miles. The first sign of Erzurum was the airport where, or course, we stopped for a wash and clean up. It was a half-baked little field, run jointly by Turkish Airlines (a Douglas DC-9 of theirs took off during our visit) and the Turkish Army (who had a handful of Piper Cubs based there), but the runway was as long as those at Heathrow Airport in London, necessary because of the altitude. We drove into the town for a meal, a visit to the shops, a bank visit and a little exploration. Then it was time to press on again towards the Persian border. After dark we drove into the village of Agri and closed down for the night at a petrol station, after a meal and playing some music for the amusement of ourselves and the natives.

The villages were pretty basic in this district, block-shaped houses being made out of clay and stone with glassless windows. Many villages were without electricity and at night the only signs of life were oil lamps glowing in the darkness, creating an exotic and intimate atmosphere. Those communities that did have electrical power had bare bulbs swinging from poles and wires in the streets, the whole arrangement looking very dubious. Other common sights were battered loudspeakers attached to the same poles, providing a medium for local announcements, advertisements and occasional music to be broadcast in the streets - Turkey's equivalent of a local radio station. The area was also very liable to earthquakes, and there was a bad one at nearby Lice in 1975, and another to the south at Muradiye in November 1976.

In the morning we drove straight out of town and made for the border, stopping only for breakfast and a clean-up by the roadside. The weather improved as the day wore on, despite a gusty wind, and one o'clock saw us having lunch beside the road in blazing sunshine. As we were eating, a few Turkish Army jeeps came by with little pennants and signs heralding the imminence of a military convoy. For nearly an hour we basked in the sun and watched the trucks, tanks, jeeps, half-tracks and guns roll by. There seemed to be no end to the column. The soldiers peered at us and our van with grinning disbelief, occasionally waving or making dubious Asian gestures. One truck driver was watching us and waving so enthusiastically that he failed to notice his truck leave the road and flatten a road sign.

A few miles down the road we came into Taslicay, a small settlement boasting the district's hospital, and stopped to visit an adjacent garage for petrol. The van was promptly approached by inquisitive villagers led by a man who turned out to be the only doctor. Doctor Hikmet Macit insisted that we came over to the hospital and had a cup of tea. Since there was a bitter wind blowing, despite the sunshine, I hoped we would be entertained inside, but he chose to seat us on a bench by a low table outside the main door and his gardener fetched us all tea. I imagine the reason for keeping us exposed was his pride in having foreign visitors, and we were soon joined by a crowd of local people, including hordes of children from the school next door.

Taslicay Hospital; the gardener, the nurse, Dr Hikmet Macit, John and me. Photo taken by Wolfgang. 21 April 1970.

His English was only just decipherable but he managed to introduce his wife and children, and a little Turkish nurse who John immediately set to work on. She was extremely shy and John was wasting his time but, after a lot of effort, he did persuade her to join us while Wolfgang took a rather bad photograph and the gardener took a worse one. Dr Hikmet gave us his address so that we could post him copies of the photographs and pleaded with us to let him buy our battery tape recorder. We politely backed out of that but said we would certainly call on him on our return journey and would consider the matter again at that time. Then we had to take our leave, as we wanted to cross the frontier into Iran that day and had heard this could be a lengthy business. After many farewells we left Taslicay and, grateful to be back in our warm van, headed east again for Persia.

Taslicay Hospital; Wolfgang, Dr Hikmet Macit, John and me. Photo taken by the gardener. 21 April 1970.

The last town before the Persian border was Dogubayazit, famous for little other than the inevitable extensive army camp and a particularly fierce prison, well-renowned amongst drug offenders of all nationalities who had been caught at the very thorough frontier dividing Turkey and Iran. As we were leaving the town, a Turk flagged us down and explained in the international language of signs and universal words that he desired a lift to the border for himself and two friends, one of whom was a policeman. We bundled them in, hoping our policeman might help to speed our transit through the frontier, and sat in embarrassed silence for the rest of the journey, since no-one was able to make contact with anyone else.

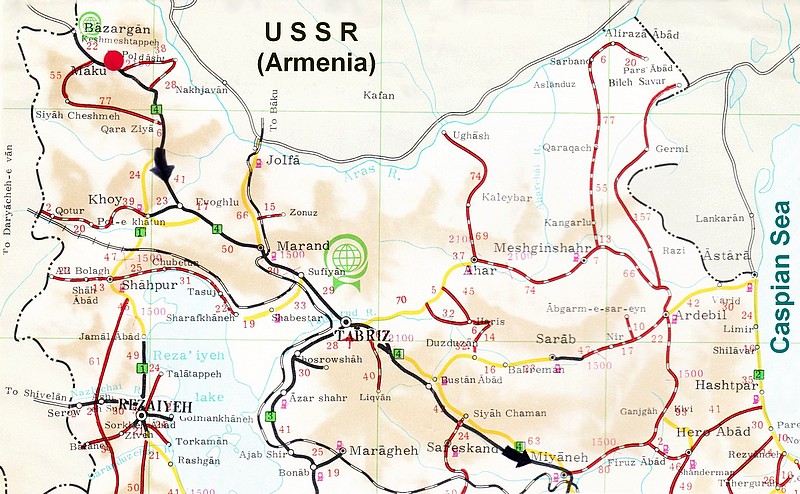

The frontier at Bazargan was notorious for being long-winded and queues were common, sometimes necessitating hours of waiting, perhaps overnight. It was only 40 miles from the Soviet Union (or what is now Armenia), just south of Noah's famous Mount Ararat which was visible from the road, and beside a small hill with a Turkish flag on top. The border post appeared to have been built as a simple square fort with later modifications incorporating an arched gateway at each end and a low dividing wall across the middle. A gap in the centre of this wall, protected by a chain, was the border proper. Sentries patrolled the wall on both sides and only they could remove the chain.

We entered the courtyard on the Turkish side and offloaded our passengers. The transit procedure was certainly very thorough and we obtained no assistance from the policeman. All our documents were examined minutely by a miserable bespectacled official who appeared not to enjoy his posting one bit. All went well until, without a word, he stood up and walked out into the vehicle park to inspect Dougal. After examining the engine for a while he announced to our amazement that the engine number on our engine was not the same as that declared on our documents. This was a problem we had not foreseen. The engine (which must have been changed at some stage, unknown to us) was not the original one listed in the vehicle's British log book, and all details on our other documentation had been transcribed directly from that. Our little Turkish customs officer wasn't at all happy with this state of affairs but, after half an hour of wrangling, he finally stamped the Carnet de Passage and let us through to the Iranian side.

The Persians took nearly twice as long, as they wanted to inspect and list in our passports every radio, record player, tape recorder, and other items of perceived value on board. Unfortunately we had rather a lot of these, but somehow we genuinely forgot to mention the spare engine under John's bed and they never saw it. At least they provided a tea shop, which gave us a chance to while away the long wait in some comfort. Finally released into Iran after two and a half hours at the border (and a one and half hour time-change) we were immediately struck by a surprising change in the road surface. Though narrow by European standards, the downhill run to Maku was smooth and comfortable, and more than welcome after the Turkish commando course to which we had become so accustomed.

After all the time spent at the border, there was no chance of reaching Tabriz that night so, when we drove into the little town of Maku in the early evening, we decided to call it a day. Maku was a spectacular place, bounded on the north by a sheer cliff some 400 feet high into which caves and houses had been carved as a protection against the rigours of the desert. In recent times the village had spread away from the cliff and the main road now ran about 1/4 mile from it. We were welcomed by stamp-collecting children and the young owner of a small cafe who spoke halting English and invited us in for refreshment. After introducing us to his brother, who claimed to be a champion boxer, he turned the conversation towards the inevitable buying and selling of our possessions - especially our binoculars; so we politely took our leave, but not before I had taken the opportunity to try out my Farsi for the first time, and found to my surprise that, in this part of Iran, they don't speak Farsi at all, but a sort of Persian/Turkish blend called Turki.

When the time came to go to bed we found the police station and made ourselves known to the officer on night duty, a friendly jovial fellow dressed like a Highway Patrolman with what looked like a Sten Gun or an Uzi at his waist. We got the message across and he let us park at his gate, wishing us goodnight incessantly and standing guard over the van as though we were royalty. Just as we were settling down he decided to sing us a lullaby, so he climbed up on our tow-bar and began to wail some traditional Persian song while, drumming his fingers on the roof, rocking Dougal by jumping up and down, and crashing his gun against the back door. This was obviously highly amusing to him, but very distracting for us. It took a while to discourage him, but we finally succeeded and managed to get to sleep.

Maku, Iran, with inhabited caves cut into the cliff. 22 April 1970.

Next morning I was not at all well. Fortunately the others were fine and after a wash and breakfast (both provided by our friends in the cafe) we prepared to depart. As usual the van was surrounded by inquisitive children trying to practice their sketchy English while appealing for stamps or cigarettes. One small boy held out his hand and announced "I am English money collection" (weren't we all?) but it got him nowhere. We soon noticed that a group of the children had assembled behind the van and were peering underneath. John and Wolfgang went back to see what was afoot and found that one of our tyres had developed a large blister on the inside wall. So for the first time since leaving Eastbourne we had to change a wheel which was, however, a pretty good record. We gave the children the damaged tyre and, as we left Maku, a crowd of delighted youngsters bowled it off down the road. If it had not been for them, we might never have noticed.

I retired to bed again which made a change, since the only ones who usually slept by day were Wolfgang and Dolmus the squirrel. Dolmus turned out to be an extremely lazy animal, spending most of the day asleep in John's fur coat, waking only when we thrust a nut at him. This would only work about twice a day, after which he would go straight back to sleep. We did wonder if the cold weather had made him think it was time to hibernate. We had weaned him off milk and onto water, which he drank out of an egg-cup. For food he only ate almonds, turning up his little nose at everything else. One day we bought him a huge box of almonds and, as an experiment, put him in the box, immersed in a sea of his favourite food. He sat there motionless, as though stunned and amazed by the concept of being surrounded by such endless joy. Other than food his choice of entertainment was destroying matchboxes, which he did very thoroughly and noisily. Occasionally he would attack the woodwork in the van and once chewed up the cover of our daily log book. When he condescended to wake up he would sometimes come into the cab and sit on the driver's shoulder or arm, peering out of the window, which made him a great crowd-puller whenever we stopped.

The others woke me as we pulled into Tabriz airport just after mid-day, where we had some refreshments with two Iranian Air Force meteorological officers who spoke quite good English with an American accent, having been trained in the United States. They told us what an excellent place Tehran was and how easy it would be to find work there. Then after watching the arrival of the daily Iran Air Boeing 727 (there were no other aircraft on the field) we left to look around Tabriz before continuing towards Tehran, driving all night. Any thoughts of trying to find employment in Tabriz had clearly slipped our minds.

We switched our batteries again at the top of a ridge outside the city (only the second change since leaving home) and drove into the semi-desert. A little further on we came across a Persian soldier and a jeep with a sheep in it parked by the roadside and apparently broken down. When we stopped, the soldier asked if we could tow him 2 kms to the nearest village. We agreed and hooked him on. However it was a lot further than 2 kms to the village and, when we got there, he indicated that he wished us to continue. After about 100 km we stopped and confronted the soldier, who gave us some petrol from his jerrycan and asked us to carry on, so we did. Every time we stopped and objected he would say it was just a little further on. He finally halted us at Zanjan at a quarter to midnight, 250 kms from our starting point, and bought us all kebabs and cups of tea. Then he bade us farewell and disappeared into an army camp. We never did find out about the sheep. I retired to bed and the others began the long night drive to Tehran, exactly one month and 5,000 Miles from home.

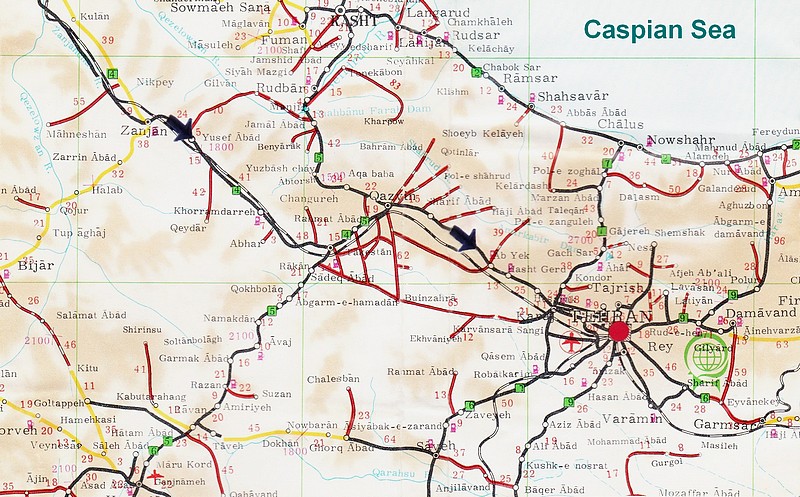

I awoke fully recovered in a busy city street in pouring rain, alone in the van. Dougal had safely driven into Tehran, in spite of the erratic antics of Persian truck drivers. John and Wolfgang had stopped at the airport to stretch their legs and have a cup of tea, and found it very busy, even at seven in the morning. The campsite Gol e Sahra (which meant Flower of the Desert) was not too far from the airport and the boys had checked in. It was a good modern camp located about 6 miles from the centre of Tehran, alongside the Saveh Road and the railway which ran south west to Saveh, Isfahan, Shiraz and ultimately Kerman, over 700 miles away. It was currently occupied by several people we had met in Istanbul. John drove into the city to find the Poste Restante and met a nearly bald Persian boy who wanted an English letter translated.

It was at this point that I woke up. The three of them presently returned to the van and the boy acted as a guide for the rest of the morning as we visited the British Embassy who told us that (a) residence permits were very hard to obtain, and took months, and (b) nobody would employ us with a transit visa. However it might be possible for our visas to be extended, and we should visit the Aliens Office, although they didn't know where it was. Next stop was the B.O.A.C. office where I learned that my services were definitely not required. Apparently foreign firms had an obligation to employ a high proportion of indigenous labour, and B.O.A.C. had no further allocations for British staff. We were escorted by the Persian boy to a small cafe where he introduced us to the traditional local meal of ob ghousht (literally water and meat, a kind of beef stew). After eating, we left him there and returned to the camp for a clean-up and the opportunity to take stock of our impressions.

The city was built where the slopes of Mount Damavand, peaking at 18,400 feet in the range of the Elburz Mountains, levelled out onto the central Iranian plateau, a vast area which was largely desert, 4,000 feet above sea level. Those who could afford it built expansive properties in the higher northern district of the city where water, trees and cooler air were more plentiful. The Shah had his summer palace there and prominent citizens tended to settle in this rich residential area. Those of lesser means lived in the dust, heat and sand of the south, but even here an attempt was made to plant trees along the pavements permitting a degree of shelter from the sun.

However it was rain, rather than sun, that proved to be our problem that day. The shower that had woken me was one of several violent spring downpours that we witnessed during the day. Although they seldom lasted more than five or ten minutes they were nonetheless very intense and were sometimes accompanied by hail, seemingly strong enough to break windows.

For the next few weeks we didn't always keep our daily log updated, but instead I wrote general observations of life in the city, so here is the first. They are, of course, the amateur (and probably misinformed) ramblings of a young foreigner!

-----------------

1. LIVING WITH THE WEATHER

It seemed to us that Iran was a very simple country climatically - the weather was either very good or very bad, with both conditions taken to their extremes. Of course our only experience was northern Iran, but it appeared that people were well prepared for the good weather, but were often caught out by the bad. That may have been due to the limited availability of forecasts. When it rained, it started instantaneously, though the sun may be out and the clouds overhead look quite innocent. We didn't experience long periods of rain, and usually a downpour was only temporary but fell with incredible violence.

Broad, open storm drains (known as the jube) at the sides of the road were also used for garbage disposal, washing up, and laundering clothes by those without better facilities. When it rained the water would pour downhill across the city and fill up these gulleys in the lower southern parts. In a matter of minutes downtown traffic would become paralysed, roads and pavements flooded, shops and houses awash, and the smell of drains would be everywhere. When this happened people would try to get into the buses and taxis, while men rolled up their trouser legs and gave stranded pedestrians lifts on their shoulders, bicycles and carts until the Iranian sunshine soon dried everything out again.

Poor picture, but fun nonetheless. From the Tehran Journal, one of two English-language local newspapers, on 25 April 1970. The caption reads "JOY RIDE - Two pushcart operators give passers-by a welcome helping hand in downtown Tehran after torrential rains flooded the capital's streets on Thursday" (which was the day we arrived).

Sometimes vicious winds would spring up out of nowhere and blow dust into everything with a destructive force but, like the rain, it would stop as though switched off. On the other hand, the sunshine was a condition that Iranians were born into. The temperature reached into the 80s Fahrenheit several times in the first few days after we arrived, and it was only spring. Soon there was to be no more rain and the temperature would top 100 degrees at times. Unsurprisingly most people had a siesta in the afternoon, because the heat tended to bring everything to a stop anyway. So all shops and offices normally closed between 1 and 4 pm - sometimes longer - reopening until 6 or maybe 8 in the evening. We soon got used to the new timetable.

-----------------

On our second day in Tehran, at half-past five, we went in search of the Aliens Office to get our visas extended. The difficulty was that nobody seemed to know where it was - not the British Embassy, not the Tourist Office, nor the Police Station. Eventually we learned of its location by chance, in conversation with an Armenian who had been there. It was big enough - surely someone had noticed it! Owing to the time taken to locate it, heavy traffic and flooded roads, we didn't arrive in the vicinity of the building until after seven, and by that time the office was closed, of course, so we were told to return on Saturday. It then took us an hour and a half to get back to the camp, a distance of only five or six miles.

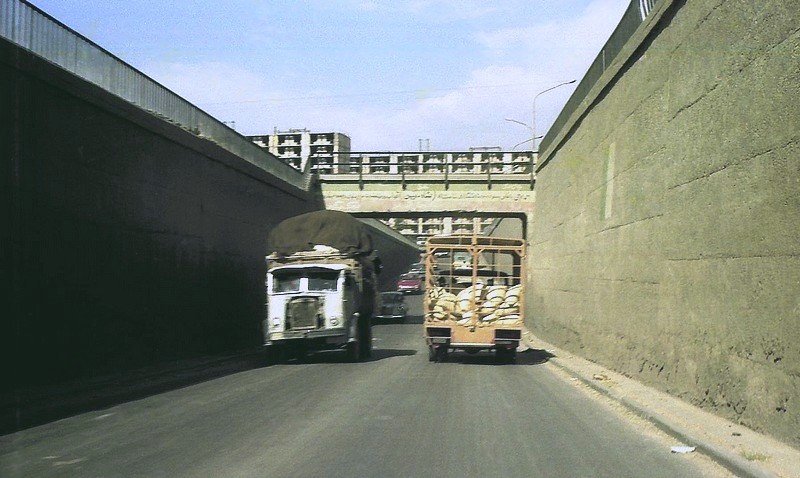

At one point on the way out to the campsite the road dipped down briefly under a railway bridge. Unfortunately this dip had filled with rainwater and there was a long queue of traffic on both sides of the underpass while vehicles ran the gauntlet through the flood one by one. Lined across the railway bridge parapet were crowds of Persians enjoying the fun. The highlight of the display was when motorcyclists inevitably fell off when their engines stopped at the deepest point in the middle, to the roars and cheers of the crowd on the balcony. The Persian sense of humour was geared to just this sort of occasion, and a good time was had by all (except those who fell in).

The underpass on the Saveh Road, south Tehran, which always filled with water when it rained. Crowds would gather on the bridge above to watch traffic getting stranded.

Friday is, of course, an Islamic holiday and we spent the entire day at the campsite. We were grateful for the chance to clear up various domestic commitments resulting from our eight-day drive from Istanbul, and Wolfgang and I set about washing ourselves, Dougal and our clothes, while John made an inspection of the van's nether regions.

-----------------

2. THE INFLUENCE OF RELIGION

One obvious sign of Islam in Iran was, of course, the veils worn by the women - more often the older ones. The status of women in Iran was gradually changing with education and prosperity taking more girls away from the home and into the workplace. We were told that the harem concept was also history and the law had restricted polygamy. Apparently men were not now allowed to marry a second wife without (a) the consent in writing of the first wife and (b) satisfying the authorities that they had the means to support more than one spouse. It had become a luxury that few could afford. Persians seemed to have had resigned themselves to the fact that marriage was too expensive for young men, and most boys at the colleges and universities didn't expect to marry until they were at least thirty, yet they might still marry girls of fifteen or sixteen. Meanwhile the girls' parents arranged marriages and maintained the chastity of their daughters, unless the suitor was wealthy or important enough to make it worthwhile speeding up the system.

Another symbol of the religion was the large number of beautiful mosques, which varied a little from those we had seen in Turkey, the architects having concentrated more on mosaic domes and less on minarets. Some of the mosques were really huge, featuring spectacular domes decorated with pale blue, intricate designs, both inside and out. Spindly minarets were to be seen however, and it was from these that chanting mullahs could be heard calling the faithful to prayer on Fridays.

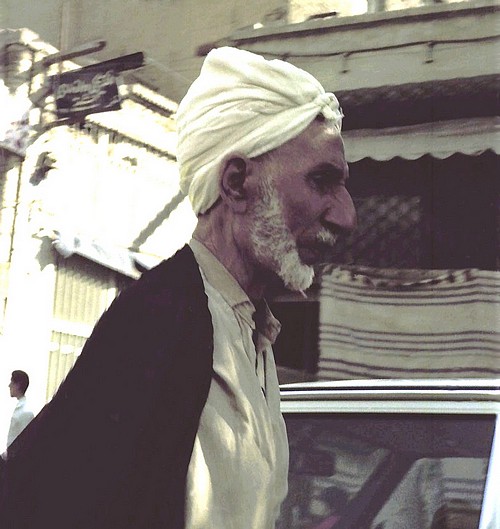

A priest in Tehran.

All the shops closed on Fridays, the Islamic holy day, but were open on Sundays of course. They also opened from perhaps 7 in the morning until 8 at night (apart from the afternoon siesta) and this led to the curious anomaly that Iranians in Britain felt that our shops were never open! They couldn't go shopping early in the morning, or late at night, or on Sundays, so were unable to comprehend our system at all.

Strict Muslims shouldn't touch alcohol, so it was probably the influx of foreigners in recent years that had boosted the beer, wine and spirits trade. The beers and wines made in Iran were not exceptional, but not bad considering they were new to the game, and local vodka was gradually acquiring quite a following. Many Persian parties were completely devoid of alcohol however, as it wasn't really part of the culture - a thing almost unknown in European countries. Nonetheless these parties, from our experience, could be riotous, and sometimes almost destructive!

-----------------

In the afternoon, and purely by coincidence, we met some friends of the camp manager who had come to visit, including a Mr Eghbal who was Tariffs Superintendent of Iran Air, the national airline. After a chat explaining our intentions of employment, he gave me his card and told me to call at his office in the morning. Perhaps it was not what you knew, but who you knew that mattered! The camp was pretty comfortable and provided laundry facilities, decent bathrooms and showers, a small cafe, television, a swimming pool and rooms for hitch-hikers. We tried the pool and found it a vast improvement on the one at Istanbul and very welcome since, when the sun was shining, temperatures soon exceeded 80 degrees F. The television had two black and white channels - the American Forces Network and one in Persian. Though the production of the latter was rather amateur, it did provide us with a source of amusement while we had supper. Both stations were broadcast from transmitters up in the northern part of the city, at the top of aptly-named Television Street.

Entrance to the Gol e Sahra campsite, Saveh Road, south Tehran.

That night we made friends with some new faces at the camp, and became particularly attached to a young American couple, Michael Taft and Sue Berkowitz, who were touring Europe and the Middle East in a brand new Volkswagen camper. Like so many others, Michael had just completed two years in Vietnam with the US Army and had been given a lump sum of cash and a Pan American ticket home from Frankfurt. So he bought the van in Germany, called his girlfriend over from the States, and was now touring around while he had the chance, flying home free when his money ran out. Though somewhat bitter and cynical about the world that had sent him to war, Michael had a wild sense of humour, and he and Sue were having a whale of a time. We rounded off the evening by forming an impromptu blues band which entertained an international young audience until far into the night.

Our appointment at the Aliens Office led us to a small room in which sat several solemn, uniformed Persians, none of whom spoke English. We managed to get our message across in simple Farsi and pigeon English to one of the officers who, after a lot of deliberation, put a stamp and a few scribbles on our passports and said, accompanied by many smiles and handshakes, that we could stay for three months. When I called on Mr Eghbal in his clean, bright office in Villa Avenue he and his assistant Mr Daftari (who both spoke excellent English) tried hard to get me employed by Iran Air but without success. While I was fed with tea and cakes at their expense, it was gradually revealed that Iran Air would only employ British people on application from England, and that a work permit was essential. However both Mr Eghbal and Mr Daftari were extremely helpful and immediately set about trying to suggest alternative sources of employment. Among these ideas were an executive flying service at the airport, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and - a very interesting train of thought - teaching English at the Iran America Society.

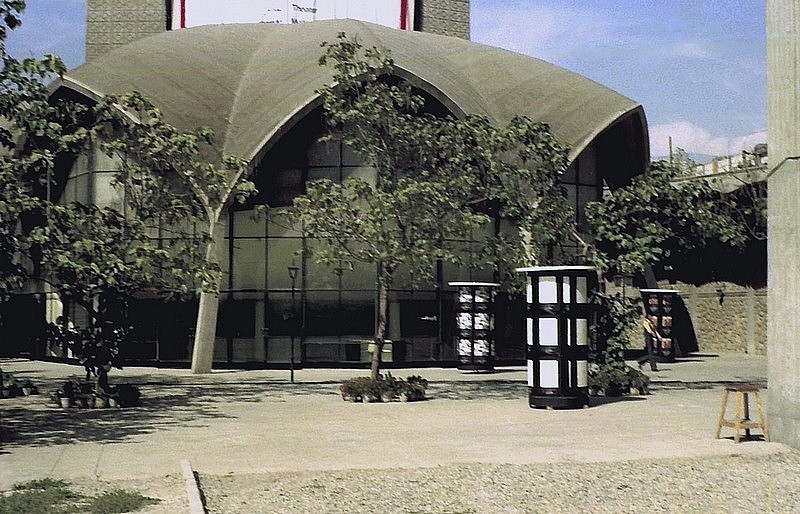

The cultural headquarters of the Iran America Society, Television Street, north Tehran.

The cultural headquarters of the Iran America Society (IAS) was a modernistic domed structure in the northern part of the city, up Television Street, where the TV and radio studios and transmitters were located. The aims of the Society seemed many and varied to us but it was officially to promote understanding and cultural bonds between the two relevant nations. It was obviously solidly supported by US Government funds, closely attached to the Peace Corps and the diplomatic service, while some other rather clandestine activities may have operated under its cover. They ran classes in English and other subjects, held public exhibitions and educational films, had an amateur dramatics group and a host of other activities. The IAS building became a social hub for Iranian students and various international young folk who were in town. We were to visit the place quite frequently during our time in the city and it soon became apparent that many people associated with the IAS were in the US armed forces, which suggested that perhaps the Society was a useful facade for US intelligence activities.

Anyway we followed Mr Eghbal's advice and went to find the place. Under the dome was a spacious cafe in which we met some of the regulars including idle, immature Dan, spoilt son of one of the senior tutors, and "E H Christenson, the most valuable man in the Air Force", or so it said on his desk plaque, although everyone knew him as Chris. He was a tall, bearded man in his late 20s, employed by the United States Air Force as a radar expert, and he was in Iran in an advisory capacity, though he seldom spoke of his work. We never saw Chris contribute anything to the IAS but he was constantly using their facilities. For him, the Society was a convenient centre for servicemen. He lived a few hundred yards up Television Street in a secure apartment with remote-controlled locks and voice communication from the front door, both of these being quite common in Tehran, though not in England at the time, in our experience. The flat was comfortable by American standards, with modern furniture, high quality stereo and plenty of popcorn.

The view up Television Street towards the mountains, seen from Chris's apartment.

Chris had considerable experience of Tehran and the Persians, and was able to provide us with plenty of useful advice. He recommended that we concentrate on teaching English but forget about work permits because we would never get them. This was sound advice since all the jobs suggested by Mr Eghbal fell through, including the IAS. So it became inevitable that we would have to teach English unofficially with no permits, unless something better turned up.

-----------------

3. THE CITY

Tehran was pretty neatly laid out, the centre consisting of a square of the four main roads; Shahreza (named after the Shah, Reza Pahlavi) across the north, Shahbaz to the east, Shoosh at the south and Simetri on the west. In this square, running vertically from north to south ran Pahlavi Avenue with its food shops, tea shops, embassies and schools, Hafez (named after a poet) in the middle, and Ferdowsi (another poet) which contained the British Embassy, British Council and the bazaar. Across the square ran Mowlavi (on the way to the campsite) and Sepah containing the Post Office and the Imperial Court.

South of this central area, heading out towards the desert, was suburban Tehran and the residences of the poorer people of the city. To the west was the university, large areas of waste land and building plots and the civil airport Mehrabad. Parallel with Shahreza to the north was a major street - Takht-e Jamshid - containing just about everything that wasn't in Pahlavi, and Takht-e Tavoos bordering onto the wealthy residential district, the Iran America Society, the radio stations and, as the ground rises at the foot of Mount Damavand, the luxury homes of important citizens, the Shah's palace and Shemiran, the mountain resort area. Finally to the east was the industrial area, more modest habitations and the military airfield Qaleh Morghi. Most of the streets were lined on either side with trees and the jube. (Of course, since the 1978 Islamic Revolution and the fall of the Shah, many of the street names have changed.)

Sheep (and some goats) being led down the Saveh Road, Tehran.

Tehran was certainly intriguing. There were signs everywhere of westernization, yet it could not pose as a European capital. Despite the flamboyant roundabouts with their pools, flags and fountains, the wide streets, office blocks and neon signs, new shops and smart houses, the effect was turned on its ear by a man leading a donkey or a flock of geese down a dual carriageway. Most street names, shop names and advertisements were in Farsi and English, indicating what was a nationwide move to bring English into general use, even if the English spelling sometimes fell short of accuracy. The traffic was dense and slow-moving, and everyone jay-walked, but we didn't come across many major accidents.

On the whole the city seemed to have tremendous character, but this was largely due to the personality of the population. My initial impression was that the eastern influence gave Iran life, and the Western influence was killing it.

-----------------

The Tehran bazaar was in the older southern part of the city and although its 15th century origins made it relatively new in comparison with many others, it had still been an important trading post on the Silk Road. It closely resembled the markets of antiquity in that it was based more on wholesale trading and exchange than on tourist appeal, unlike its counterpart in Istanbul. Though not as big as bazaars elsewhere in Iran (Tabriz has the largest in the world, by far), it was still a challenging labyrinth of little lanes and we were grateful on our first visit to be adopted by a persistent Persian porter who, though apparently endowed with cousins and brothers in every trade of the bazaar, was at least able to show us the way out.

One of several entrances to the Tehran bazaar.

As we emerged into the sunlight we were approached by a smartly-dressed man in his early thirties who spoke erratic English at great speed. His name was Hamid and he seemed to be especially interested when we mentioned that we were looking for work. He told us that he was a gynaecologist and had many useful professional contacts around the city. During the following few days Hamid guided and escorted us around Tehran, introducing us to new people and interpreting. He wined and dined us, put an advertisement in the Persian newspaper at his own expense, quoting his post office box number which he religiously checked every day for letters from potential employers.

His story was somewhat confused and some of it we attributed to his wild imagination, but he told us that he was dissatisfied with Iran's political constitution and the Shah so, with a large number of others, he had rebelled and objected in some way of which he never spoke. The result of this was that he had been arrested and beaten up by the police. Now a marked man, he had decided to leave the country and go to England, but the authorities had refused to provide him with a passport. As a last resort he had married an English lady while she was on holiday in Tehran and he was now waiting for the necessary papers to permit his departure. His wife, Monica, had returned to England and he hoped to join her shortly but, though he claimed they were very much in love, we felt that he was really only in love with the idea of leaving Iran, and that her affection was based on a probable cash incentive. He was confident of getting the necessary papers but it seemed likely to us that, without Monica on the spot he could still run into difficulties.

-----------------

4. COMMUNICATIONS

John and I sat in on an English lesson at one of the many language schools, and the students were writing short essays. The teacher, who was English, gave a free choice of subjects, and three of them chose the Telephone Problem. We were curious to find out what the problem was. The National Geographic magazine described the Tehran phone system as "An instrument of torture that has been known to cause brave men to weep. Actually to complete a call on the first try is like winning the national lottery." Lesson One - there weren't many phone boxes. I tried to phone someone one day from a phone booth but could get no dialling tone, so I tried another booth outside the Post Office, feeling that it must surely work owing to its location, but found a line of people waiting outside. This was Lesson Two - be prepared for a big queue, and Lesson Three - if there isn't a queue, it probably doesn't work. I finally got into the box but found that the numbers on the dial were in Arabic. At first I could make no contact at all but after a while I began to get a few wrong numbers. I had to dial thirty times and lost several 2 Rial pieces before I eventually got through to the chap, although he was only two streets away, and the sound quality was so bad it seemed hardly worth the effort.

Really, the telephone problem (which would subsequently be resolved by mobile phones of course) was only part of a bigger and better communications problem. Such things as railways, airports and postal systems were just finding their feet, and had got off to a rather shaky start. The enthusiasm was there but the organisation was lacking. Only Iran and countries at similar stages of development could have corrugated roads or postmarks reading 32nd December. Having said that, a lot of road resurfacing was taking place within the city and things were getting better.

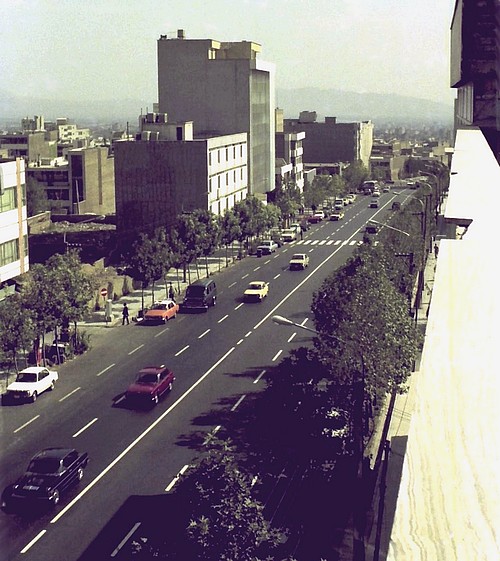

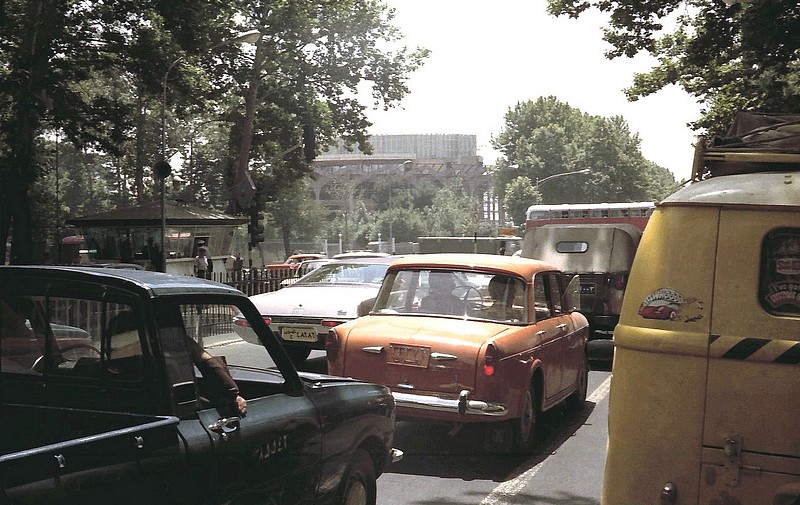

Most of the traffic in Tehran probably never left the city, dominated by three types of taxi. First were the orange IranNational Peykans (licence-built Hillman Hunters), Fiats and Peugeots - we even spotted an Austin A35; next were medium-sized light blue cars, mostly Mercedes 190s dating back to the 1950s, and finally there were the large black and yellow IranNationals of Tehran Radio Taxi. Taxis probably accounted for about one third of the total volume of traffic. There was also a bus service. Over 200 red AEC double-deck buses with Park Royal bodywork - another sale for Britain - and about twice that number of single-decker red and white Mercedes coaches, although that didn't include the many long-distance and private coaches.

One of the British-built (but left-hand drive) AEC Regent Tehran buses hurrying along Sepah Avenue.

The rest of the traffic consisted of private cars, ranging from clapped-out 1950s Mercedes saloons and Citroen 2CVs to Ford Mustangs and Dodge Darts, heavy trucks - Mercs, Macks and Leylands - hundreds of 3-wheel vans, horse and donkey carts, and infernal mopeds with up to three passengers. All this lot careered around the city, all over the road, often bumping into one another (but only gently), carving up and cutting in, blasting their horns and shouting abuse, loving every minute but getting nowhere. It frightened us at first, but then we learned that a sense of humour was the key to success. The whole thing became entertaining after a time, while the Police made only a half-hearted attempt to control it all and calm hot tempers at the scene of accidents. Mostly they just stood at busy crossroads waiting for a crunch. They were seldom disappointed.

-----------------

Much American help was employed in the construction of modern Tehran, and it was apparently they who masterminded the introduction of the city's water and sewage system. Clean water from the nearby Karaj Dam was piped to all of Tehran and sewage pipes removed the city's waste. It was said - although I find this hard to believe - that the local authorities found this a revolutionary idea at first, and had to think about it. Eventually - allegedly! - they came up with a rather cheaper system in which only one pipe was laid and it would carry fresh water by day and sewage by night. Whether or not that story is true, expats living in town just shrugged this kind of thing off and accepted it as a fact of life, local colour - Persian version.

Wolfgang had now decided to travel on to Nepal but as yet had no transport. A husband-and-wife team, part of a convoy of two Land Rovers at the campsite, had separated after a furious argument. He had joined the other party, which left his wife Margo with the Land Rover, unable to drive but still determined to continue her journey. John swooped in at this stage, apparently to listen to her troubles and console her but, as soon as he had gained her confidence, he recommended Wolfgang as a driver and introduced him. She accepted the idea and it all looked promising, although Wolfgang later confided to us that he had never learned to drive, but felt that he would get away with it! We hurriedly gave him basic driving lessons in Dougal around the campsite.

Typical parking bay for camper vans at the Gol-e-Sahra campsite. That's probably Michael Taft's VW camper.

For Wolfgang it was now only a matter of obtaining a visa for Afghanistan, and a few days later he drove the Land Rover out of the camp on the next stage of his remarkable journey, much more of which is related at the end of this story. Wolfgang and Dolmus left our adventure at the same time. Dolmus was always free to walk around outside the van in the camp if he wished, and his habit was to sit in the shade under the wheels. One day we unwittingly ran him over as we left to go into Tehran. Michael and Sue saw it happen and buried him while we were away, breaking the news to us on our return. Although less of a tragedy, we also said farewell to the last of our instant porridge and breakfast cereal, neither of which seemed to be replaceable in Tehran.

-----------------

5. THE PEOPLE

Iranians were a constant source of surprise and delight to us, being very different from Europeans. They had a marvellous sense of humour (we found it the easiest thing in the world to make a Persian smile) and seemed to be universally happy people. Life was simple for many, and it took little to distract them from monotony. In Tehran we only met the rich fleetingly. They tended to live in the north of the city and drove flashy cars. A middle class seemed very similar to those in Britain and, in the same way, sometimes were quite intolerant and disparaging of those of a lower status; but they were always sociable and generous to us.

At the next level were the poor and the workers, who could be boisterous, noisy and friendly, but were also often inclined to idleness - happy to lean on a shovel all day if they could get away with it. No wonder the modernisation of Tehran could be a slow process! Finally there were the very poor, begging on the street or relying on the most menial of jobs, cleaning windscreens, shoe-shining, sweeping the streets, or assisting in tea shops - sometimes by breaking up sugar lumps or spreading water on the floor to keep the dust down. They were to be found all over the country, and in Tehran at night could be seen dragging themselves along (in company with old opium addicts), in search of a park bench, a seat or a peaceful bit of pavement for the night.

Street beggar in Tehran.

Old men had grey beards, moustaches and wrinkled faces from years of sunlight, while younger men often had classical Persian looks and western, stylish clothes. The girls were either veiled and invisible, or rebelliously modern, with trouser suits (or even more daring clothes), bright colours and intricate Persian patterns. Mostly they still maintained the shyness and mystery of their heritage however, or maybe we just scared them. Their mothers were nearly all veiled, although not hiding themselves as much as the stricter Muslims outside Tehran. Their chidoor veils, gently patterned in drab browns and maroons, exposing only the upper part of the face, were held in the teeth and wrapped over the top of the head.

On the whole we got on very well with the Persians, and the other nationalities in town. Tehran was definitely very multi-national and tolerant of just about anybody. Assyrians and Christian Armenians were common, as were Westerners from Europe and the USA. More surprising perhaps were the Jews, and we also got to know a Sikh who only slept 4 hours each night, so he took up oil painting because there was nothing else to do or people to talk to at 4 in the morning.

-----------------

In our search for employment a pattern was emerging and we felt we might be getting warm. The channel that showed the most promising results was the teaching idea, and we found that we were in considerable demand from the many English language schools around the city centre. It appeared that everyone wanted to learn to speak English, particularly students, technical workers and executives, for which they were prepared to forfeit their spare time and pay handsome fees. Several of the schools were interested in using us, since the standard of English taught by the local teachers was not always great, and real Englishmen were invaluable for conversation practice with the more advanced students. Nobody asked us if we had work permits, which was convenient, and many of the students we met invited us to give private classes in their own homes, for which they offered to pay us well. Some of the schools seemed a little makeshift so we reserved our judgement until we had seen a few more.

The view south down Television Street from Chris's flat.

Meanwhile Hamid continued to check his post office box and finally we had a response to our advertisement from a small company named Asayesh, which described itself as a domestic service agency. We all went round to their offices and found a clean comfortable building in a side street north of Takht-e-Jamshid. Hamid had to translate for us as neither of the two men who met us spoke English.

The manager, a fat, bald fellow who said "Bali, bali!" ("Yes, yes!") continuously when spoken to, explained that he wanted to employ English salesmen to promote his various services among the American and English residents of Tehran. He particularly favoured the English because he felt they were viewed as more honest and persuasive! These services consisted of redecoration, carpet-laying or carpet purchase consultancy, indeed he seemed tempted to try his hand at anything that people might want. He offered us good cash rewards on a commission basis, and a spacious office on the first floor of the building, with a new carpet, new office furniture and a balcony. We said we needed time to consider it.

Another possibility was suggested at this time by Hamid, that of teaching English to the Persian Army. The Army camp was on the eastern side of the city near the military airfield of Qaleh Morghi, and we had difficulty finding it as it was in a district that we seldom visited. We were herded about the camp by armed escorts in search of the correct department, and were finally ejected because we had no work permits.

Leaving the camp turned out to be as difficult as finding it. Every turning among the maze of back streets was labelled NO ENTRY and John was becoming very frustrated in his attempts to rejoin the main road. Finally he disregarded the signs and swung into a narrow one-way street at the wrong end. When we were half way up, an Army Jeep turned in the other end and drove towards us. For some inexplicable reason John decided to accelerate. As we neared the Jeep and John saw the whites of the occupant's astounded eyes, he realized that he had left himself the choice of either hitting the Jeep or driving into the jube at the edge of the road. He elected to hit the Jeep and it struck us just behind the cab, tearing the bodywork down the side of the van and practically detaching one of the double doors. We were lucky that the Jeep was unharmed as the repercussions of the incident might have been quite serious if the Army had decided to take the matter further. On other occasions John had a similar rush of blood to the head and would fail to stop in a crisis - I never got to the bottom of this extraordinary behaviour but I also never challenged him about it - we got along too well for that.

Dougal in Tehran traffic, heading down Pahlavi Avenue. In the background is the City Theatre, then still under construction. The orange taxi is a Fiat 1100 licence-built in Iran.

That wasn't our only accident in Tehran. I ran into the back of a small van in a traffic jam but the driver didn't notice. On another occasion we were approaching a busy crossroads in Takht-e-Jamshid when a taxi in the lane on our left pulled across the white line and hit us in the same place as the Jeep. We were travelling quite slowly and there was no damage, so we felt there was no need to stop. As we waited at the traffic lights the taxi driver ran up to us shouting, opened our driver's door and took our ignition keys. We were amazed but, since we now had no way of moving, there was no choice but to leave the van where it was, get out and wait. Apparently in Iran after an accident the vehicles concerned had to remain where they were until the police arrived, so the taxi driver had foolishly left his car straddling the white line. He refused to return the keys, and the policeman who was directing the traffic said he was too busy to deal with the situation and radioed for someone else. Meanwhile a queue of cars was piling up behind us and a crowd of gaping Persians was assembling in front. We climbed onto the roof rack and sat on top, staring back at the spectators and waiting for further developments. Soon a traffic cop arrived on a motor cycle and had a long conversation with the taxi driver. It must have been obvious who was in the wrong because of the position of the offending taxi so, after a while, the policeman came over to us, returned the keys and said "You can go, Sirs."

-----------------

6. THE COST OF LIVING

Our master plan in Tehran was to take advantage of the cheap way of living adopted by those of lesser means, while availing ourselves (without any guilt whatsoever) of the hospitality offered by the more fortunate. It seemed to be working okay. Particularly with regard to food, we bought local and paid less, but accepted every invitation for a free lunch.

The monetary system was pretty straightforward for conversion; £1 Sterling bought around 183 Rials at a bank, or 188 or so at the exchange shops. So, taking a round figure of 200 Rials to the Pound, that gave us 5p = 10 Rials, known locally as 1 Toman although this denomination was unofficial and didn't appear on banknotes or stamps. Petrol was 6 Rials per litre, equivalent to 3 Pence, which compared very favourably to the then current British price of 30 Pence per litre, but then the stuff did grow out of the ground down south in the oilfields. We complained in Tehran when only the higher grade fuel was available at a petrol station, which was a bit ridiculous in retrospect.

Income tax in Iran was a universal 10% of income. In Britain at the time it was proportionate to the salary level, reaching 30% for incomes above around £1,500 per year. Imported commodities such as cars, cameras, radio and TV equipment cost the earth, sometimes twice the British cost. Then there was the bazaar, a very important centre of commercial exchange where, in theory, everything was cheaper; but, like all bazaars, the stranger often got swindled and ended up paying more than necessary! On the whole, the cost of living was lower than England. You would pay more to rent a flat, but less to stay in a hotel. The overall cost was lower because the standard was often lower, but we made a few adjustments and compromises and found Iran a fine place to live.

-----------------

One evening I saw a young man carrying a guitar case and, as with Drago in Ljubljana, I felt that was a good reason to talk to him. Naturally I was hoping to find work playing guitar and the young man, Vahid, invited us round to his friend's house for an instant audition which seemed to satisfy the assembled group. There were six of them altogether but they sometimes divided or played as a smaller band when necessary. The bassist, organist and rhythm guitarist we never got to know very well, but the other three became good friends of ours. Vahid was the drummer. He was a polite, intelligent boy of about 20 who spoke excellent English and worked in his father's firm near the bazaar. Jongy, the lead guitarist, was a charming bright young man who spoke seldom, and never in English. Unfortunately he had soon to enter the army, and I think the idea was that I might replace him. We liked him best of all, but speaking to him in Farsi all the time could be strenuous.

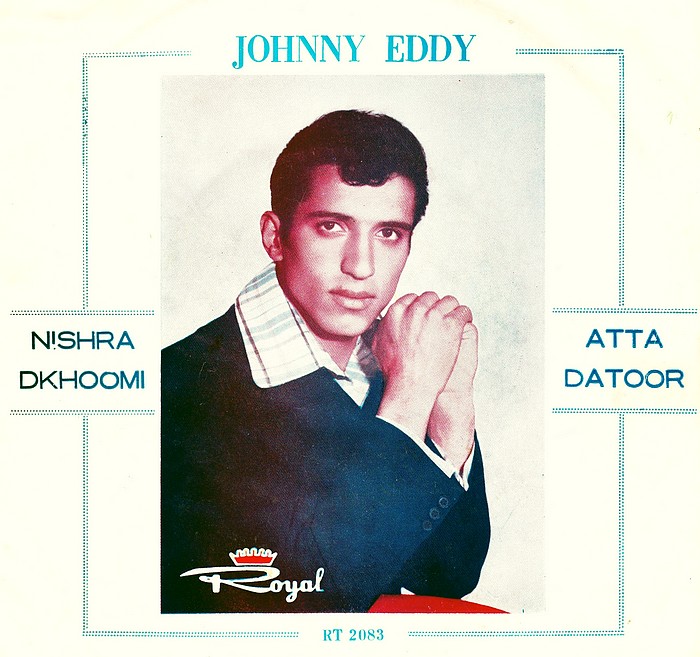

Finally there was singer Johnny Eddy, who had a good, strong, adaptable voice and a confident, extrovert personality - just what you want for a front man. He was Assyrian, one of the several close-knit national groups in Tehran, and firmly believed that his country should be returned to its people (the Assyrian homeland is presently in Iraq and part of Syria) who kept alive the language, script and traditions. Johnny Eddy recorded patriotic songs in Assyrian, with his separate and much better band The Tehran Boys (we never found out who they were) but this was probably not a very commercial proposition. He gave me one of his records and it was very well done. He also gave me a business card for himself and the Assyrian's Star Band but we never found out who they were either. After the audition the boys were due to perform at the Castle Club, a social venue for American forces families. They invited us along, which was a wise move since they had no idea where the club was and we found it for them. When we arrived, one of the guitarists was missing. After a while the manager of the club started to get impatient so I volunteered to fill in while we waited. This further established good relations with the band but it turned out to be the only time I ever played with them.

The record sleeve from Johnny Eddy and The Tehran Boys' nationalistic Assyrian songs Atta Datour and Nishra Dkhoomi. Written by Johnny Eddy, arrangement by Howeek, issued by the Taraneh Company, Takht-e-Jamshid, Tehran.

Really they were a terrible shambles and lacked any organisation. They could never get together for a practice or, if they did, the evening was always spent in a bar talking about it. They were given a five-month nightly booking from one of the best night clubs in town, but then quit because they wanted more money. They gave up a weekly recorded spot on Persian Television because they said they were short of material. Later they cancelled all engagements so that they could make a record, but couldn't resolve an argument about which songs to use. Their music was based on fair imitations of average, slightly dated Western pop songs (Tom Jones, Jose Feliciano, James Brown etc), which went down well with Persian audiences on the whole. At any rate it was material which I could handle reasonably well, so it all looked promising when we left them that night.

Johnny Eddy (real name John Adi) died in 1993 but a video of the song sung by his sister Romena Jonas along with recordings of Johnny is available on YouTube here.

Another useful opportunity came from the Nejad English School in Pahlavi Avenue. Of all the schools we visited this was the largest and it seemed efficient and well organised. It was in a six-storey building opposite the Shah's Marble Palace, and had about eight classrooms, a cafe, a staff room, air conditioning, showers, and a domestic staff who kept the tea urn permanently hot. The atmosphere was pleasant and Mr Nejad, the principal, offered us teaching posts commencing in a few weeks when the summer term began, provided that John got his hair cut.

Maidan-e-Sabzeh (Sabzeh Square), courtyard of the Soltani Mosque by the main entrance of the Tehran bazaar.

Friday came round again and we were very pleased with the past week's work as we lazed about in the sun or dipped in the pool at the camp, in between attempts to restore Dougal's dignity. We managed to get both the side doors to open, after a fashion, but the battered panelling was beyond repair. I washed the van thoroughly and applied another coat of paint on worn areas (including fresh gloss white on the roof to keep us cool) while John inspected the engine. It appeared that the loss of power we had noticed since leaving Istanbul was due to a loose cylinder head, and John solved the problem with the firm application of a spanner. The heater had also been giving trouble and John had been obliged to keep it permanently in action. Now, with the hotter weather and summer approaching, we decided to disconnect it completely.