The Classic British Isles Buses Website

An overland trip from England to Iran in 1970

Story by Richard Gilbert.

Part Four - Turkey to Eastbourne

Last updated 4 September 2024

Email Events diary Past events list Classified adverts Classic U.K. Buses Classic Irish Buses Classic Manx Buses

Driving through the Turkish mountains towards Erzurum. 13 June 1970.

We awoke on the second day to the sound of the pure mountain water tumbling over the rocks outside our window. Hollow wooden gutters diverted some of the stream water to a tap and trough on the veranda of the hotel, and this was the village water supply. Azmi had plans for a small hydro-electric plant in the gorge to provide power for the village and he had bought himself a generator. He suggested that, since John had expertise in such things, we could stay and build the plant for him, but we declined.

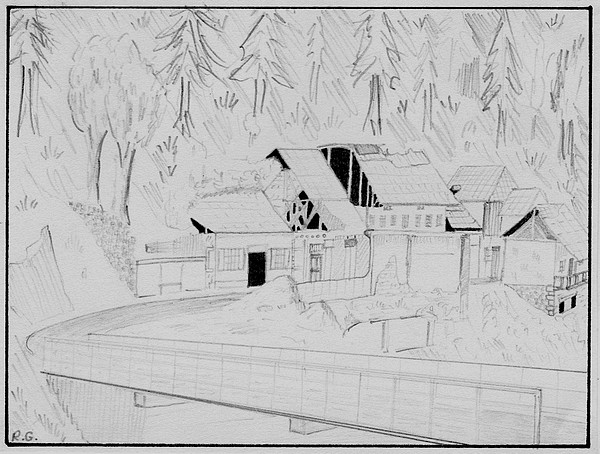

The weather was beautiful so, while John sat outside the hotel trying to do as little as possible, I spent the day sketching and taking photographs, along with a stroll up the river valley to a mineral spring about a quarter of a mile up the hill. Once out of sight of the village all signs and sounds of human activity disappeared and it felt very remote and primitive. No rubbish, no distant sound of traffic - we hadn't seen or heard an aeroplane for days. This was another place where I could have spent a much longer time in investigation and appreciation.

Sketching made us quite popular and we drew some pictures of people's houses and a few portraits, which resulted in a more friendly but still curious attitude from the locals. In the afternoon I made a passable drawing of the man who ran the tea shop and, in return, he provided cups of tea and a lesson in Turkish draughts, that strange game that used to occupy Dr Hikmet's evenings. Afterwards he hung the portrait on the wall of the shop. Communication was getting easier as we picked up a few Turkish words (Hello, goodbye, please, thank you, water, bread, milk, tea, car, house, up, how much, and where is it?) and discovered that some bits of Farsi were common to both languages. We also came across a boy who spoke some French and another who knew about a dozen English words.

Kalkanli; a rough sketch from the Hotel Kulis looking across the gorge to the eastern side of the village, and the mountain road heading off to Iran.

On the third day John felt that we should be moving on despite his neck so, after farewells to all the locals, we prepared to depart and asked Azmi for the bill. He wrote two different figures on a piece of paper and said that he had three prices. If a guest had no money then he owed nothing. If he had a little money then he paid the lower figure; but, if he felt he could afford it, he paid the higher one. We paid the higher one. At 10 o'clock we gingerly steered Dougal back onto the road and left the village, amid waving and shouting, bound for Trabzon once again.

John suffered in every way. Each bump in the road was agony and he was very bad company. I was now doing all the driving and I enjoyed it, but this only frustrated him more, because he liked driving too. To make matters worse, when we had reached Trabzon and were driving alongside the Black Sea we were surprised to find, not the overcast grey windswept coast with which we were familiar, but glorious sunshine and vivid deep blue water. John longed to jump in.

By late afternoon he'd had enough, so we halted in the small coastal town of Unye and John booked into a cheap hotel for the night, being unable to worm his way into the coffin-sized bed in the van. We strolled along the beach and listened to an abominable pair of Turkish youths who were producing agonizing, random noises on electric guitars - and presumably being paid for it - until, when John could stand no more, we had an early night.

In the morning I rolled up at the hotel to collect John and within minutes we had attracted a crowd of onlookers: I counted them - 33. The coast was superb in June and, if it had not been for John's condition, we might have stayed for quite a while. As it was, we felt obliged to keep heading homewards although, by the time we had reached Samsun where the road leaves the coast to head south towards Ankara, we had come to the conclusion that John ought to visit a hospital, whatever the cost. A tourist office on the sea front directed us to the state hospital which was up in the hills behind the town. It was large, modern and well-equipped, and we were welcomed by a team of shy but fascinated nurses who helped us when they could, and stared at us when they couldn't. While John was being examined by a friendly Turkish doctor who spoke English like a native, I wandered about, accompanied by a growing entourage until I had accumulated so many that the hospital begin to miss them, and they finally got moved on.

By the time John was released he had received two X-rays, a diagnosis, a packet of analgesics and the good news that he had nothing broken, but only an abrased muscle that would heal if properly rested, which was unlikely to happen in his case. Even more surprising was that the hospital refused any payment, and we were grateful for that as every penny was beginning to count. Now at least we knew what the problem was, and John dutifully took his pills. He found that they reduced the pain but were short-lived in effect.

We moved into the Samsun campsite which had opened for the summer season. John elected to rent a tent since he still couldn't climb into his bed and anyway would soon become too stiff to get out again. The manager was interested in our guitars and asked us to play for the camp that night. He had a small open-air stage and at about 8 o'clock we set up the gear and began a concert to about a dozen children who soon lost interest. Later some young Turks asked if they could play our instruments and proceeded to sing national songs while bashing anything on the guitars. We left them to it, but had earned ourselves free accommodation for the night. It surprises me in retrospect that we didn't use this method of paying our rent more often.

It was during our stay in Samsun that we learned of martial law being imposed in Istanbul after riots by militant left-wing workers. Thousands of demonstrators had rampaged through the city causing injuries and a few fatalities as tanks rolled in and soldiers fired into the air. The disturbance had apparently spread to Ankara where students joined the protests. We hoped that it wouldn't affect our transit through both places. Thankfully it didn't.

Next door to our patch was a retired New Zealand couple in a Commer van and they were a fascinating pair. The husband had apparently been a commercial artist and they had promised themselves a world tour when he retired so that he could paint and sketch on the way. Their children had left the nest and, when the great day came, they picked up their life savings and set off. We met them a year and a half later after they had been through South East Asia, North America, Britain, Scandinavia, Central Europe and North Africa, having bought and sold several vans en route. His paintings were magnificent, ranging from Florentine bridges to scenes in a Marrakesh market, all beautifully captured and stacked in a pile at one end of the van.

Before leaving we gave the couple a model of Dougal that had been given to us before leaving England and, in return, they gave us two Maori Tiki good luck charms. From that moment onwards our luck went steadily downhill - clearly they were evil Tikis. That day we had our first tyre go flat, followed by another immediately afterwards - we must have run over something nasty I suppose. Near Ankara we met a vehicle with a worse problem; a Ford truck had left the road (we guessed the driver had probably gone to sleep) and inverted itself and its load of eggs in a field. A team of looters grinned sheepishly at the camera when we photographed the incident. Heaven knows what they expected to retrieve from the king-sized omelette that remained.

Looters pose for the camera at the scene of an overturned truckload of eggs near Ankara. 18 June 1970.

It was dark by the time we reached Ankara and we were getting tired as we searched for the campsite. If we had found the main BP camp, as intended, I might have met my wife six months earlier, as she was passing through the city in the opposite direction that night in a Minitrek party. However, we didn't, but settled instead at a smaller place with limited facilities and only two other occupants, a gay Irish photographer and his Pakistani assistant. They were bound for Lake Van on a photographic tour. That district, in eastern Turkey, had a reputation for wild remoteness, marauding robbers and mysterious deaths. They knew all this but were still prepared to make the journey by bus and foot. In the morning we had our pictures taken and our addresses noted but, not surprisingly, we never received the promised copies of the pictures, nor heard from them again.

We suffered from the Tiki curse again that night because, when John crawled out of his sleeping bag in the morning, he found that he had been bitten by something in his left eye and a huge swelling had appeared, reducing his vision considerably. His neck was still giving him trouble, of course, and to top it all he had acquired a headache and stomach trouble. Towards lunchtime one of the tyres we had fitted the day before went flat and later I nearly got us both lynched:

I was driving through a village, perhaps a little too close behind a truck which obscured most of my forward vision, when it pulled out towards the centre of the road to avoid a cow (unknown to me) which was walking out in front of it. I couldn't see the cow but pulled out as well, assuming that there was some obstruction. Suddenly he braked hard and I knew that Dougal could never stop in time, so I had the choice of overtaking into oncoming traffic which I couldn't see, or passing on the inside. I decided that the inside was the safer option (being unable to see a thing anyway) and as we swung over I saw the cow. She had wandered out in front of the truck until it stopped, then turned back. There was nothing I could do. Braking frantically I came up alongside the truck and hit the cow in the jaws with our crash bars. Immediately bystanders stared at us appalled and John wisely recommended that I get the hell out of it. The truck had stopped completely so we had a good start on him, and I was relieved to notice in the mirror that the cow had started to graze again by the roadside, apparently still reasonably intact.

The Maori Tiki good luck charm given to us by the New Zealand couple, but which brought us nothing but bad luck from that day onwards - probably because his head fell off.

Nothing went right that day. A few miles short of Izmit I spotted a police VW Beetle parked on the verge and, as we approached, I felt in my bones that he was about to pull out in front of me so I slowed. Sure enough he swung straight out at us and I swerved to avoid a collision. It was all so predictable - the police wanted an excuse to stop us and the little incident was as good as any. He soon caught up and flagged us down. Two flat-hatted patrolmen climbed out wearing pistols, leather jackets and sunglasses. They had obviously seen too many movies and I felt like Al Capone. The spokesman leaned in the cab, looked over his dark glasses and said "Passport Control", a pretty good international phrase to get the ball rolling. After he had examined all our documents he pointed out that we had no insurance, which was true as a result of the oversight by Turkish Customs at Bazargan. He said it would cost us 200 Lira (about £6) and we knew we'd never get a receipt.

After some fruitless argument John rolled up a few notes and handed them over after demanding that we got our passports back first, a typical touch of his insight into such things. We drove off immediately and John confessed that he had only parted with 30 Lira (less than £1) but they would have to unroll it and count it before they'd find that out. Fortunately the police obviously considered the matter unworthy of further pursuit as a few minutes later they roared past us on some more important errand which lay in the road a few miles further on, under a sheet surrounded by blood and onlookers. This was the only time we had to bribe police.

With darkness, the temperature dropped to a reasonable European level and, as we rounded a bend, the lights of Istanbul spread out before us. Signs marked Ferry Bot led us to the Uskudar landing stage, and soon Dougal was safely aboard and we were drinking tea and watching the lights of the old city approach, while wondering how we managed to miss all the other poorly-lit vessels that criss-crossed the Bosphorus. So, with Asia behind us for the last time, we rolled into the BP Kervansaray Mocamp and, after cold showers (not by choice), went quickly to sleep.

We had a plan for our stay in Istanbul, based on a desperate need for more cash. Firstly we decided to sell the spare engine. Our own motor was doing fine (or so we thought) and we felt that the value of the spare would be fairly high in Turkey because of the import duty (which we had not paid) but it would decrease as we went into Europe. Besides, Istanbul was an ideal place for a little slightly illegal trading. Our second fund-raising exercise was to be the collection of a couple of riders - paying hitch-hikers. If we could split the high cost of European fuel we stood the chance of being able to relax a little along the way. On the first day, because I was the only one who could drive for any time, I managed to leave John at the camp with all the dirty clothes and washing up, while I went into the city to put a note on the Pudding Shop notice board announcing our requirement for riders. For good measure I pinned up another at a nearby Youth Hostel.

In the afternoon, after writing letters home for a change (we weren't very good at that) we went back into the city to wander round the Grand Bazaar again, where we bought some Turkish puzzle rings, and instantly met our first customer. Lyn was English and wanted a lift to Hammersmith but couldn't leave until Tuesday, and it was Saturday. We agreed to hang on for her, as we still wanted to find a second passenger and had not yet sold the spare engine. By our newly-estimated calculations, we had completed 11,000 miles.

Next morning we awoke to find an extra body in the van, asleep in the cab. It was the property of our new resident who got up and made breakfast, which was an excellent start. However we were very uneasy about this mixed arrangement and it led to a couple of weeks of argument and sniping. From experience we found that this was the normal period for a total stranger to settle in - indeed John and I had two weeks of subdued tension on the outward journey. We had broken one of our golden rules, and we knew it. Before our departure several girls had asked to accompany us and but we swore we wouldn't carry females. With one girl on board, either she would feel the boys were ganging up against her, or she might foster a rivalry between the males. With two girls there would inevitably be a pairing-off which could only work if both couples were in harmony all the time - rather unlikely for months on end without a moment's break. Not only that, it could cramp the style of all concerned if a dusky maiden or a bottom-pinching Italian Romeo came on the scene. It would only work once in a blue moon, and we didn't get many of those.

Anyway Lyn seemed a pathetic, aimless, brainless hippy to me, while John fancied her like mad because she was there. She resisted John effectively and, over a period of time, proved me to be a very poor judge of character. She was in Istanbul on a mercy mission; an old flame of hers had been arrested the year before on drugs charges and was serving his time in the local prison, so Lyn had hitch-hiked from England to bring him some books, clothes and a friendly face. It was not an easy thing to gain access to a Turkish prison and the necessary red tape was keeping her waiting until the following Tuesday. We thought she was brave to make the journey on her own but she shrugged it off. Apparently she had set off with £12 and still had £7 left, which she gave to us.

Selling the engine was easy enough, provided that we kept our wits about us. The jovial attendant at the car park opposite the Pudding Shop, who didn't really remember us but was willing to pretend anything for a few Lira, put us in touch with a smooth-talking hustler who said he would buy not only the engine but the whole van as well. To get rid of him we told him that we had stamps in our passports that prevented us from leaving the country without Dougal, which was true. He said that, if we gave him the passports, he would erase the stamps and return them next day. Even I laughed at that - the going rate for a British passport was £40 and he wasn't getting ours, especially for nothing. It was a trick that had succeeded in the past however, and there were some sad faces around to prove it.

Another good scam that worked well on broke hitch-hikers was this: first arrange a drugs delivery to a European city and conceal the goods in a smart car. Then find a naive youngster prepared to drive it and tell him you have sold the car and want it taken to the new owner. Offer him say £20 plus petrol costs with a promise of another £20 on arrival at the destination. If he gets caught, nobody will believe his story or give him the chance to find you again, and if he completes the run successfully you've made perhaps £1,000 clear profit depending on the load. Once the driver crosses into Greece the details will be stamped into his passport so he'll find it hard to sell the car in Europe, he can't sell it in Turkey without the documents of ownership, and he can't drive it east without a Carnet. Many a young man regretted falling for that one. Mind you, if he's clued up he'll buy a forged Carnet in the bazaar, drive the car to Pakistan and sell it for twice its value, so make sure he's not too smart before you hand him the keys!

We moved on to the bazaar, parked the van on the pavement outside, opened the double doors and displayed the engine adorned with a sign marked 1650 TL (about £50). A crowd grew and began to haggle amongst themselves. I'm not sure that anybody actually wanted the engine to begin with, but an auction was irresistible. Eventually we got to the best price, 1,400 TL (about £42.50) - not as high as we had hoped but a pretty satisfying result overall, we thought.

Returning to the Pudding Shop we found no responses to our note, so I maintained a vigil while the others went shopping. From the upstairs window one could see across the busy street to the serenity of the Blue Mosque, which was remarkable enough, yet within a few hundred yards was the magnificence of Saint Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom, 1,400 years old, originally a Christian church, later a mosque and finally a museum but surely the most ambitious and outstanding place of worship in the world. The builder, Emperor Justinian 1, on seeing the finished article for the first time is supposed to have said "Solomon, I have surpassed thee." Even the Blue Mosque was considered controversial when built because it had more minarets than its counterpart in Mecca. Between the two, in the heart of the ancient city, sat the Pudding Shop, an inauspicious title for a place of great importance to our journey and possessing one of the finest views in Europe.

A photo that John took of the back of the Blue Mosque, Istanbul.

Just round the corner was another haven for the traveller in the midst of Istanbul's bustling activity, a tiny cafe tucked in beside the Saint Sophia mosque. Yener, the proprietor, was a philanthropist. He thrived on the company of passing travellers, hitch-hikers and temporary residents, welcoming them all with a smile, a cup of tea and the cheapest kebabs in the city. If the heat was oppressive one could spend a refreshing hour or so eating his home-cooked Turkish food and chatting to the other occupants in transit to all corners of the globe. Yener would sometimes nip out and collect some fresh bread, shellfish or plums and share them around his poorer customers free of charge. His handouts were unnecessary in our case but, for those with no money like Lyn or Wolfgang, they were manna from heaven.

Somehow Yener's never attracted real bums, it always seemed to be full of live characters, perhaps like a Parisian cafe in the days of Lautrec; and on the subject of art, visitors were invited to contribute to Yener's scrap-book, a collection which had already run into two huge volumes. Yener put the current book on the table in front of us during one of our visits and we thumbed through it. It would take perhaps a week to read, being a veritable treasure trove of sketches, paintings, poetry and prose in dozens of languages and as many styles as its contributors. Some of the artwork must have taken days to complete while the creator waited for a visa or a wire from American Express, or simply hibernated from the sun. Much of the work was so good that we felt afraid to put pen to paper beside it, but John, the artist of the piece, drew a splendid cartoon of an animated Dougal champing at the bit, and we added a few words of thanks to Yener for his generous hospitality.

At the Pudding Shop we were getting limited success in our search, but so far all the applicants had been couples and we really couldn't cope with that. We gave up in the early evening to return to the camp and met a family from Macclesfield with whom we spent an interesting few hours, eating, drinking and chatting on a wide variety of topics. It was nearly midnight when the parents finally went to bed and we all felt that the generation gap had closed a bit.

The British Embassy was situated high on the Beyoglu promontory, hidden among steep winding lanes that snaked up from the Galata Bridge. Here Lyn was to receive authority to visit the prison, and we went along too. Within the high walls and peaceful gardens of the Embassy confines we felt safe leaving Dougal unattended for once, though we still secured all the padlocks as usual. The Embassy, as we had come to expect, was spacious, comfortable and Victorian with lily ponds, antique furniture and aspidistras, but a grim reminder of modern times hung on the wall in the reception room; under a heading warning Britons of drug misuse were rows of passport-type photographs of Europeans and Americans who had been executed in Iran in recent years for possession of narcotics. In Turkey a stiff prison sentence was common but in Iran you were shot.

Lyn was having trouble gaining access to the prison and she was told that she would have to wait another day because they had to arrange for a representative from the Embassy and also someone from the Turkish authorities to accompany her. Another day of waiting followed but no further replies to our note were forthcoming, so we took it down and decided to keep our eyes open for potential passengers as we went along.

The day did bring forth one surprise however, when we bumped into Nick the Gem, the elven character we had previously seen in Tehran. He was delighted to see us and it soon became obvious why - he was still carrying his unwieldy 16- string Afghan rubbub, which was becoming quite a liability. Hitch-hikers prefer to carry as little as possible and Nick wanted to offload the unplayable instrument onto us. We unwisely agreed to take the instrument to Eastbourne for him, and he agreed to collect it later. This is exactly the sort of thing which we should have avoided, as the sealed soundbox of a musical instrument could be used to conceal anything. On this occasion we were lucky - the instrument was clean - so after another unsuccessful attempt to play it (I broke a string), the ghastly thing was stowed away and presented no further problems.

When Tuesday arrived, John and Lyn drove off to the prison while I washed clothes and tried to keep sheltered from the fierce sunshine, which gave me the opportunity to get to know some fellow residents better. One English couple in a VW camper had a remarkable history. For their honeymoon they had bought the van for a three-week tour of Sweden but enjoyed travelling so much that the newly-wed husband sent a cable to his father pulling out of the family business and requesting all the money in his bank account. He then took a job in Sweden for a while, moving on when the mood took them and gradually working their way east. When we met them they had been on the road for eight years!

We had been adopted by an excitable Californian teenager travelling with his parents and bored to tears. A little light came into his life each time he went into the city and saw the collection of vintage American cars ("You wouldn't believe it... I saw a 1951 Hudson Hornet today!") but the rest of the time he was very depressed, and listening to anti- US propaganda broadcasts on Eastern European radio stations only made him worse. He soon became exhausting company and our sympathy waned.

For the first time on the whole journey I had the opportunity to spend a bit of time with a member of the opposite sex. Barbara was a nurse from Leeds on an organised trek holiday and, when John and Lyn returned, they both hated her. We were going our separate ways at the crack of dawn the next day anyway, so that was that. Curiously we only succeeded in making each other slightly homesick, an unfamiliar sensation for me but one that was to make the remainder of the journey take on a new character, all of us now wanted to get home.

Intense heat encouraged us to get on the move promptly next day, as we packed everything neatly and topped up our various tanks. At 9 o'clock we signed out of the Kartaltepe Mocamp and drove onto the motorway, past the airport and out into open country bound for Greece once more. Near the border we pooled our remaining Turkish small change and bought varied bits and pieces to use it all up. We also came across an Iranian 500 Rial banknote which must have been overlooked at Maku. It was annoying to have £3 tied up in money that no-one would exchange.

At the Greek frontier we were ushered over to a special compound where a heavy plain-clothed officer prepared to make a thorough examination of Dougal. He was obviously searching for drugs and began by poking the spare tyre on the front, which was flat. "If you're going to take it off and look inside would you mind changing it for this one while you're at it?" said John, never one to miss such an opportunity. The fellow ignored the remark and asked how long we had been in Afghanistan. When we explained that we hadn't been there at all, he changed completely and let us go without further ado, an indication of just how infamous Kabul had become. That night was spent at Alexandroupolis in the same campsite as before.

Greece was at its finest - a scorching hot sun, red earth, avenues of trees, green rolling hills, olive groves and a backdrop of deep blue sea and a cloudless sky. Neat white houses contrasted with the blueness to form the national colours which turned up everywhere, even on little wayside shrines that dotted the countryside. As we travelled west the world grew cleaner and greener, and the Mediterranean weather settled down to a glorious warm continuity more acceptable to the European. It took some adjustment however, and we found that we had become so used to Asian faces that the Greeks looked English at first.

It was mid-afternoon when we reached Kavalla again, searched out the same exotic camp where we had first met Wolfgang, wasted no time in getting down on the beach and, for the first time on the entire journey, went swimming in the sea. The camp had become a busy tourist trap but we were happy to wallow in its comforts, especially since the charges had doubled since our previous visit in April and we felt we might as well get our money's worth.

Lyn in the sea at the Kavalla campsite. I think she's wearing one of John's shirts.

That night Lyn complained of a pain in her side, which became so bad by the early hours that the camp manager, with John's assistance, drove her to the local hospital where she was admitted as an in-patient with pleurisy. In the morning she told us that it had happened before and she would be all right in a day or so. This left us with some unexpected time to kill and, in between visits to the hospital, we lazed and swam and watched the water skiing while considering the possibilities. One idea that very nearly came to fruition was a visit by ferry to the island of Thassos just off the coast. It only failed as the result of extreme idleness.

Part of the ruins of ancient Philippi, near Kavalla. Nobody there - I bet that's changed! 26 June 1970.

Lyn became a very impatient in-patient at the hospital, such that we were obliged to convince her of the need to stay, though admittedly by the second day she seemed much improved. In the morning I persuaded John to visit the nearby ruins of Philippi, a city founded in the 4th century by Philip II of Macedonia. Acres of stone pavements and fallen pillars are all that remain and little is recognisable except the amphitheatre - they always age well. Though the sun had been shining on the coast, a gentle drizzle fell upon the ruins from an overcast sky and the silence, broken only by the occasional scrape of a passing tortoise (no guides or tourists), encouraged us to return to our beach. That night we met five London lads eastbound in an old Bedford Dormobile. They were eager to know what to expect further along the road so we bought a bottle of wine and spent the rest of the day recounting travellers' tales while poring over maps and notebooks.

The Bedford Dormobile on its way from rainy London to sunny Australia (see the back doors!). Kavalla. 26 June 1970.

Lyn more or less walked out of the hospital on the third day, though she was granted grudging approval by the doctor who must have realized it would make little difference whatever he said or did. Our visits to the hospital introduced us to a new breed of travelling animal, the blood seller. Broke hitch-hikers, who soon learn all the tricks of the game, could sell their blood for about £8 a session, a performance which could be repeated every few days if necessary, though in combination with the poor diet usually common to their way of life, it often took its toll on their condition and was not recommended.

That afternoon we did very little, for Lyn's sake, which meant sitting on the beach. John and I hired kayaks and paddled out into the bay - John, of course, had to fall in and invert his canoe. The fact that he could swim and play the fool again indicated that his neck must be getting better, or at least he was learning to live with it. Either was a good sign. Lyn paddled a bit and discovered a vicious sea-urchin that took great pleasure in leaving painful spines in one's feet. This little monster abounded along the Aegean and Adriatic coasts and frequently was only discovered the hard way, though it could be seen in clear shallow water, being black and about 2 inches across. Its spines broke off at the surface of the skin making them extremely difficult to remove, and we found that the least painful solution was to leave them there for a couple of days until they worked themselves out. We named the creature the Lesser Adriatic Nasty.

In the evening we went into town and found that it had a fine Roman aqueduct in excellent condition. It was apparently built to carry water to a Byzantine acropolis on a small hill at the end of the promontory that separated the two bays of Kavalla. If you are confused as to how a Roman aqueduct could supply water to a castle built hundreds of years later, I'll just say that the whole story is very complex with all the structures being constructed on the sites of older ones - too complicated to unravel here.

John nodding off on the beach at Kavalla after a swim.

Despite all the fun, the campsite was charging us £1 per day, which was too high for us, so it was time to move on. After an early morning dip in the sea we drove the 40 miles or so to Thessalonika and jumped back into the water again, the weather still being extremely hot. Unfortunately during the afternoon Lyn's temperature rose to 101 degrees F, so we felt the best policy would be to keep moving toward Yugoslavia where medical services for British subjects were free. Although we had not been asked to pay for anything at Kavalla we didn't feel inclined to push our luck. Lyn went to bed early but John and I couldn't resist the temptation to try a little more goulash and local wine, returning afterwards to the beach to strum our guitars into the night.

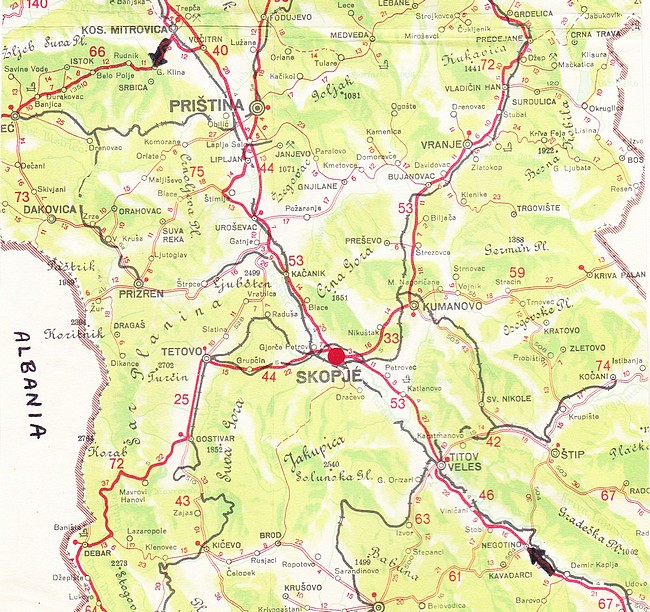

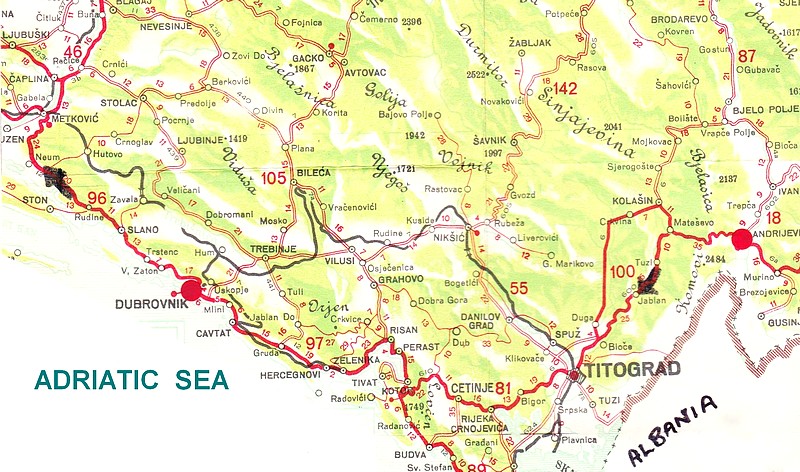

Instead of returning the way we had come, we decided to drive up the Yugoslavian coast, The route we chose skirted the Albanian border, crossed the mountains of Montenegro, meeting the Adriatic at Kotor, just south of Dubrovnik. On account of a late departure from Thessalonika we were only able to cover the 96 miles to Skopje that day, but already we had driven into a new world. The blue and white of Greece's coastal panorama gave way first to green hillsides and then, on crossing the frontier, to a hazy and more rugged terrain in what is now North Macedonia.

The River Vardar south of Skopje. 29 June 1970.

Skopje itself had the unmistakable aura of an iron-curtain city, although one of the more common features, rain, was admittedly absent at least on this occasion. Perhaps it was the shortage of cars on the streets or the austere uniformity of the blocks of flats, but somehow one was constantly aware of being under the umbrella of the Red Star. Like most Yugoslavian cities Skopje was clean and efficient (despite the awful destruction wrought by an earthquake in 1963) and the tourist office was typically easy to find and very helpful. They directed us to the adequate campsite near the sports stadium beside the River Vardar. The parking spaces and various facilities were hidden between fir and cedar trees, and it made a pleasant change for us to walk about on a soft carpet of conifer fallout. John soon made contact with an American Hell's Angel type of motorcyclist so, while they discussed Harley Davidsons and choppers, Lyn and I talked to a couple in a VW camper also heading for Dubrovnik. Paul and Kathy Smolen from Pennsylvania suffered from the same kind of wanderlust as so many of their fellow countrymen in that age group.

We chatted about our experiences and the strange country whose border was not 50 miles from where we stood. Albania was seen as the most insular state in Europe and, although usually thought to be a particularly repressive member of the Warsaw Pact countries, it was in fact as critical of Moscow as it was of the West. At the time of our trip Albania had allied itself to China - and only China. Being separated from them by thousands of miles, the Chinese were unlikely to interfere much with their activities, other than supplying them with arms and aid in exchange for minerals such as chromium and nickel. At the time, few strangers had been inside the country, whose borders were an impenetrable steel curtain through which only hazy tales emerged; but it would seem that the residents were as uninformed regarding the outside world as we were of them. Radio Tirana blasted forth bitter and radical propaganda that seemed so ludicrous to the Western listener that it was hardly worth jamming.

This tough little nation managed to avoid getting even the smallest of headlines in either east or west, year after year. But we did meet one traveller who had got into Albania by bus, in which blinds were periodically drawn over the windows (on the right or left side, accordingly to the location) as it passed through sensitive areas. She told us that on one occasion, when the bus stopped and she got out, locals had recognised her as a foreigner and threw stones at her. The other odd part of her tale was that she had bought some matches in Albania and the box was inscribed "Made in Sark". Presumably this didn't mean the tiny Channel Island of that name (one struggles to imagine matches being made of timber from the vast forests of Sark!) but I have no alternative explanation. The Yugoslavs had a ponderous joke about Albania - that the nation only had one car, one radio, one light bulb etc. This threw them into hysterics. For the traveller who desired a voyage of real discovery within Europe I thought that perhaps package tours to Tirana could be arranged, complete with the thoughts of Chairman Mao and a blindfold! (Note: that fantasy turned into reality - although without blindfolds - once the dictatorship collapsed, and I enjoyed a fascinating tour of Albania in 2019.)

The drive into the mountains proved to be quite a challenge, leading us through terrain we had no idea existed so relatively close to home. The road became increasingly narrow and primitive until finally Dougal was overtaxed and blew a tyre. Paul and Kathy, who were travelling in convoy with us, stopped while repairs were completed. Just as were finishing the job a slow procession came into view heading towards us. It took a while before we realised that the column of horses and decorated carts, escorted by sombre-faced men and veiled women in traditional costumes, was a funeral procession. The horse-drawn bier was covered with flowers and ribbons, topped by a huge picture of the dead man, presumably someone of great local significance, as the cost of such a display presumably couldn't have come easily to country folk.

About 160 miles were covered that day through breathtaking scenery, cliff-hanging grit roads, and mountain tunnels with water and bits of rock falling from the roof. At nightfall we stopped at Andrijevica, about 5 miles from the Albanian border and some 5,000 feet above sea level. On the edge of a river valley we found a small hotel that looked as though it might provide a bite to eat and some hot water. We were wrong on both counts but there was a large gravel car park in which we were permitted to camp, so out came the stove and the usual meal of baked beans, eggs, instant mashed potato and coffee, consumed while being treated to the spectacle of a million tiny red fireflies that criss-crossed the darkness down in the valley. Now that Lyn felt better John proceeded to make amorous advances, so Paul, Kathy and I talked and drank Yugoslavian beer in the bare hotel bar while John attempted to exploit the darkness and the fireflies, and Lyn stood for no nonsense.

It was just as well that we hadn't tried to continue driving at night as the final stretch to the coast was even worse than before. We'd been advised that the main road which reached the coast at Kotor ended in a murderously steep descent into the town, while the slightly longer route to Budva was preferable, especially for those with weak brakes like Dougal's. This alternative road was bad enough, as the mountains dropped straight down into the sea all along this part of the coast. We were amply rewarded, however, by the magnificence of the view as we approached the Adriatic. Unfortunately, on closer examination this area proved to be a holiday playground for German tourists, but the excellent coast road passed many of the little harbours and fishing villages, so it was still possible to find some places as they had been before the bonanza began. Our total journey reached 12,000 miles at this point.

The fabulous old city of Dubrovnik seen from the hills above. 1 July 1970.

Paul and Kathy wanted to see more of Dubrovnik but we chose to move on (my wife and I went back to the city for a holiday in 2001 to explore what is one of Europe's most glorious cities - thoroughly recommended!) so next morning we left them at the Youth Hostel and headed up the winding coastline in search of quieter places. That night we stayed at Podgora, one of several towns that later became hugely successful tourist resorts in the Makarska area. Next day was another delight as we worked our way slowly north, swimming and sunning ourselves at every opportunity. We really felt as though we were on holiday, the sea warm and blue and the weather perfect. With a brief stop at the spectacular and ancient city of Split, we continued up the Dalmatian coast making our last Yugoslav stop at Jurjevo, a small resort in the north of what is now Croatia, but not before John had incurred another on-the-spot fine for a rather over-confident overtaking manoeuvre right in front of a police car (which he hadn't spotted).

Postcard of Split on the Dalmatian coast, sent to my parents on 3 July 1970. On the back I said "I would like to return here when I have more time and money". 47 years later I did, and it still looks just like this.

The whole of that Yugoslavian coastal drive was idyllic, and a complete joy from start to finish. Having been back there a couple of times since, I can confirm that it's still just as delightful! In fact the weather became even hotter as we left the coast at Rijeka and drove through the Italian border heading for Venice. Then the Tiki curse returned and, for the first time, Dougal let us down. I was driving along the Autostrada and found it increasingly difficult to maintain speed - the engine was just not producing the same power. A change down to 3rd gear was required just to maintain 40 mph on the level. Then it started to rattle and the oil warning light came on, so I pulled off onto the hard shoulder to take a look. Our worst fears were confirmed, for there was hot oil everywhere and an attempt to test-run the engine resulted in billowing clouds of smoke and a complete seizure.

ACI, the Italian free road service, quickly turned up and hastily dragged us off their tidy Autostrada to the nearest Volkswagen agency, which turned out to be in a small town named Latisana, a mile or so from the main road. We were deposited in a narrow side-street flanked by high walls. On one side was the Volkswagen garage and a compound of derelict cars, while on the other was the back of an Italian Army barrack block. The weather was obviously heading for a heatwave.

So what had we got? A limited budget certainly (we had about £68 left in the kitty), an undetermined but probably expensive fault in the engine, three mouths to feed for an unknown period, and a language problem. On the positive side we discovered a drinking-water pump and some shops round the corner and some basic toilet facilities that existed on the railway station platform about five minutes away. At least we had our self-contained caravan parked in a quiet side street. It was too late to do much else before nightfall so we had no option but to sleep on it. To our surprise I managed to find Radio Luxembourg on John's transistor radio so, for the first time in many months, we were able to entertain ourselves by laughing, tutting, mocking and criticising the music it poured forth.

The next day was a Sunday but we got to work, intending to do as much as possible ourselves to cut costs. Morale was still high and the team worked well, with Lyn making excellent meals and frequent cups of tea, while I hovered around cleaning oil off everything and trying to do what I was told. Meanwhile the engineering department removed the engine, struggled to denude it of its elaborate exhaust and cooling system (in spite of rusted, broken and some missing nuts and bolts) and eventually began to get some idea of what the trouble might be. One piston had shattered and at least one big-end, probably more, would have to be replaced. John stripped the engine down as far as he could without the approved extracting tools (at least we had the service manuals) and then had to give up until the garage opened in the morning. The irony of the fact that, two weeks previously, we had sold a perfectly good spare engine which would have resolved this situation easily, was not lost on us.

The rest of the day was spent exploring the town. Latisana in a heatwave was the driest, hottest, dustiest, lazyist town in all of Italy and yet its aura was a friendly one. The local folk were nosey and excitable, hanging out of their windows in the evening sunshine and shouting to those in the street below. Much of the town was modern, the streets well-paved and houses and apartments whitewashed and clean; but the traditional Italian atmosphere prevailed and a strong community spirit undoubtedly existed. Latisana revolved around two centres, a market place which was also the junction of all roads passing through the town, and an attractive tree-lined square headed by a clock tower which overlooked the arbitrary space chosen as the bus station.

We had a conference in the evening to consider options for improving our financial situation. It seemed that we could be around for a while so Lyn and I might try to find work while John carried on doing as much of the repair work as possible. This was easier said than done, since many people in Italy seemed to be unemployed and two foreigners would probably not stand a chance. John even tried hawking himself round the local building sites and managed to get one or two invitations to "come back tomorrow". Lyn and I had a plan B however, which was to go to the local coastal resort of Lignano and try to find a profitable outlet for me and my guitar. Lyn would sing or dance or something.

By the end of the morning we had managed to split the engine right down, with the curious but friendly assistance of the garage staff, and the news was not good. All the big-ends needed replacing, the crankshaft was badly scored and one con-rod was bent - not to mention the broken piston which we already knew about. The German-speaking garage manager reckoned that, to buy a new set of big-end bearings, new piston rings and a second-hand piston (an economy that pained him), straighten the con-rod (this also made him wince), regrind the crankshaft, and reassemble and retime the engine, would cost at least £30.

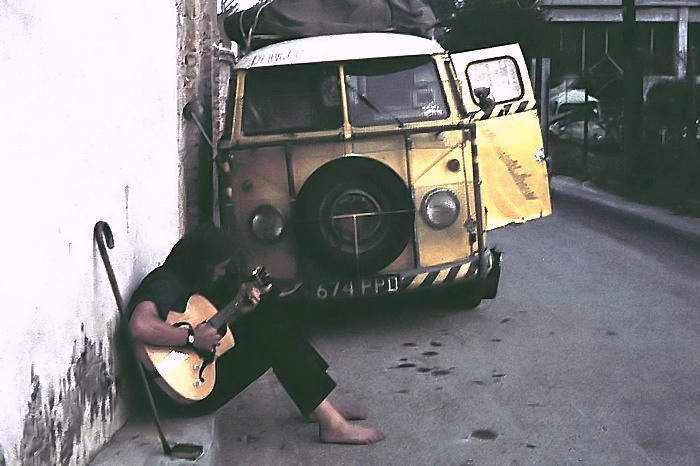

It looked as though we there going to run very low on cash unless some fund-raising enterprise could 0be initiated, so Lyn and I put plan B into operation and hitch-hiked off to Lignano to seek our fortune. John took a farewell photograph of us waving our thumbs but, when the first car stopped and politely informed us that we were standing on the wrong road hitching in the wrong direction, we sorted that out and soon arrived at the coast.

Lyn and I looking for a lift to Lignano, standing on the wrong road hitching in the wrong direction! 6 July 1970.

Lignano was a tidy, formal seaside town geared for the tourist, divided into three distinct stretches of coast. We found ourselves in Lignano Sabbiadoro, the central area, and immediately set about exploring and investigating the work possibilities with not the slightest sign of success. However we did meet some other young folk, some local, some from elsewhere in Italy and some from Germany. They took us under their wing and seemed very sympathetic towards our cause. After providing us with a meal and discussing various money-making possibilities they offered us accommodation for the night in a beach chalet they were renting.

Meanwhile John handed over the relevant bits of Dougal to the VW garage and could do nothing further until they had completed the necessary work, so he followed us into Lignano through the use of his thumb. He didn't see us, though he spent the morning trying, but did manage to get an offer of employment as an electrician with a circus. Unfortunately that meant touring with them for three months, so he had to turn it down. However the manager of an Indian bed-of-nails performer bought him a couple of drinks to improve his morale before he hitch-hiked back to Latisana.

After sweltering in the heat for a while (there was no real shade in our street - our candles were melting into one another and even the boot polish was oozing its way out of a closed tin) and being attacked by a plague of flying ants, John decided to try and join us in Lignano again. This attempt was even less successful, as the police picked him up for carrying no passport and little money. John played the fool and his harmonica, which made them laugh so they let him go. Why he was travelling with his harmonica but without his passport I cannot say.

This left him beside the road half-way between the two towns, so he decided to abandon the journey and return to the van after all. He eventually got a lift in a car containing several girls and a fellow who had met Lyn and me in Lignano. On his return he came across some English-speaking Dutch hitch-hikers whom he directed towards Lignano, an American- speaking Italian who bought him a beer, and an Italian-speaking Italian who bought him a cup of coffee, a sandwich and some wine. After a heavy political discussion in German, French and Italian, John retired to bed having done a lot but achieved little.

Postcard of Latisana market square. We were parked in the first turning to the left, behind the blue van. The cafe is now a bank.

Next morning the parts were ready and John paid the bill of £21 - a hefty lump out of our reserves - but it was really too hot to work in the open so he tried once more to get to Lignano for a swim. His luck was out again because he just couldn't get a lift, so he returned to the van resolved to get down to business whatever the weather. Several hitch- hikers passed and chatted, providing a welcome distraction.

Lyn and I spent our first day in Lignano hunting around for a suitable place to perform, and practising various songs with the group of young people who had adopted us. It was a novel experience to make music in a public street as these characters rushed about performing antics and singing, while collecting cash for our desperate plight. It wasn't long before the police put a stop to these activities and, although we had made a few pounds while it lasted, we decided it was an unsatisfactory way to raise cash. So we decided to return to Latisana next day to see how John was getting on. There was a grand farewell on the beach, with many an address exchanged and another good free meal for us both. Then we headed back, having lived for two days at no cost and had raised £1.50 profit to our credit.

John and I battled with the engine for the rest of the day, while Lyn tidied the van. In the evening we bought a bottle of very cheap wine to enhance the meagre supper (we were mostly living on bread and cheese), and it made me rather sleepy. However it had a different effect on John and Lyn who began to grin like Cheshire cats and make drooling remarks to each other. I retired to bed and left them to it. Poor John deserved some light relief. He had suffered nothing but disasters for the past few weeks and it was to be a long time before life would be so bright for him again.

John working on the engine outside the VW agency in Latisana, with Lyn watching proceedings. 9 July 1970.

The evil Tiki had one final card to play, and Thursday 9 July 1970 turned out to be a day we would not easily forget. It started off well with an intensive assault on reassembly of the engine, and after lunch we were able to put it back into the van with only the connection of fuel pipes and electrics between us and success. At about four o'clock we stopped work for a cup of tea and I sat down on our jerrycan. This can was a problem in the fearful heat and we used to keep re-positioning it beside the van so that it stayed in the shade as the sun moved round. On that particular day we had been a bit slack with the game of musical cans, and I made the horrific error of deciding to ease open the filler cap to let out any pressure that might have built up inside due to the heat. The cap flew open violently under the strain of the five gallons of hot petrol within, fuel poured out in a fountain all over the road in front of the van, anointed John's feet - he was wearing only sandals and jeans - and spread towards the lighted petrol stove.

John's reaction was to turn off the stove and attempt to blow it out. That always took some time and this occasion was no exception. I picked up the can, which was still spouting petrol, and ran off with it up the road and away from the van. Lyn was standing some distance away, unaware of the unfolding crisis. From behind me as I ran, I heard a roar as the fuel caught fire. I could do nothing for John and Lyn but I could protect the van somewhat by carrying the bulk of the petrol as far away as possible from Dougal, which contained everything we owned and was our transport home.

I kept running and looked back. There was a ball of fire right across the street and chasing me along the trail of fuel still pouring out of the can I was carrying. I was well down the road and away from Dougal on the other side of the road when flames reached my right hand. I threw the can against the high wall and ran on until well clear. There was a scream from behind the raging fire that filled the street but I couldn't tell whose voice it was and could see nothing through the flames. I thought it was possible that, as petrol flowed out of the can and air came in, there might be an explosion when the mixture was right, so I went down to a water trough at the end of the road to dunk my hand and face which had been burned as I had thrown the can. After a minute or two, there had been no bang and the flames had died down enough for me to see back up the road. There was no sign of John or Lyn, or anyone else for that matter, so I assumed that they were being tended in the garage. Tentatively I walked back past the van and looked for the others. It took some time to communicate with the Italian mechanics but they eventually managed to explain that John had been severely burned and Lyn less so.

Apparently a man calling at the garage as the accident occurred had smothered the flames on John's # body with his coat, bundled him and Lyn into his car and drove them straight to the hospital, only about five minutes away. They couldn't tell me any more and there was no-one who could take me to the hospital to find out what was happening, so they made me a cup of tea and sat me down as the reaction set in and I started to shake and go weak at the knees.

After a while John's rescuer returned and offered to take me to the hospital as well, though he spoke no English and was unable to explain what condition the others were in. Halfway there he stopped at another garage where the manager spoke a little English and acted as interpreter. He told me solemnly that the girl was all right but my friend was probably dead. My head spun, my heart pounded and something in my mind switched off and wouldn't let me think about it. This was all my fault. I don't know what I said.

At the hospital, the doorman took in the situation rapidly and told me the floor and room number I wanted. As I stepped out of the elevator I knew it was all right, because a stream of colourful language was pouring out of a doorway down the corridor, and the voice was a familiar and reassuring one. John was surrounded by staff, several of them nuns, and in the most terrible pain. Despite having had a couple of knockout injections he was bellowing the roof down as they delicately exposed the burns, covered them with gauze and sprinkled salt water on them. The nuns ignored the Anglo-Saxon but must have grasped the approximate meaning. A doctor explained to me that John was burned in various degrees over most of his body surface, just about everywhere except his legs that had been protected by his jeans. One foot seemed particularly bad and it was probable he would lose some toes, but it was early days yet and they couldn't say what the outcome would be - indeed they couldn't promise that he would survive. Lyn had sustained burns on her left arm and leg and had been put to sleep for the time being.

Apart from John's pain, it was the shock of the incident that most affected us that first day. John finally got to sleep, thank heavens, but Lyn was visibly shaken when she awoke. The doctors examined my burns and decided to keep me at the hospital for a few days as well, so I was moved in with John. That night we were all afraid of waking up in a panic as our subconscious minds dramatised the day's events, but in fact we all managed to sleep fairly well, disturbed only by the pain which was now getting established and would remain for weeks.

In the morning my mind had cleared a bit and Lyn was just about able to keep strong, but John was desperately low. He told us he wanted to die rather than suffer any longer, and he very nearly succeeded, merely by the total loss of the will to live. Lyn was remarkable. She spent the whole day trying to keep John's head above water without ever revealing how shaken up she was underneath. My respect for her advanced by the minute. On the third day, John was learning to cope and seemed to be considering recovery rather than the alternative. His wounds were turning ugly, and king-sized blisters were forming on his hands and feet. The other two had both lost some hair, and they kept getting nauseous flashbacks of the smell of it burning. Lyn, emotionally washed out now, cried a lot during the day. She wanted to go home and was probably fit enough to do it, but the doctors wouldn't let her go.

In the evening we had a management meeting. Lyn needed to go home but felt reluctant to go off on her own without any money - which brought us to the second vital factor, we were broke. There seemed no chance of moving John for a while but I would probably be released soon and could finish the repairs to Dougal, if only I could afford to live when I got out. After a lot of discussion it was decided that Lyn and I would hitch-hike back to England together. I would have to scrape up some cash from somewhere and break the news to John's parents, then return to Latisana, repair the van and wait for John's release. All this was on the condition that John felt capable of coping with being abandoned for a few days and would strive for a recovery. He promised he would.

We had quite a struggle to get the hospital to release us but, shortly after lunch, Lyn and I were standing beside the road in the blazing sunshine heading towards Milan. We tired quickly but were determined to keep going and by late evening were dropped on the southern side of the Alps beyond Turin. Our best lift appeared at this point, from a young Yugoslav in a hired Fiat 2500cc Ghia Coupe with a cracked windscreen and a Milan licence plate. We had trouble making ourselves understood but he agreed to take us to Paris, though he wouldn't say why he was going, and he obviously intended to drive all night. He took us at great speed through the beautiful valleys of Aosta and on through the gathering darkness into the snow toward Mont Blanc.

Lyn and I felt comfortable and content as we roared through the tunnel but were somewhat taken aback when we reached the Swiss frontier and our driver seemed to be detained by the Customs officers far too long for comfort. However he was finally allowed to pass and we started the long descent out of the mountains heading for Lyons and the Autoroute. At daybreak we stopped at a cafe for a breakfast of bread and Swiss cheese, and the Yugoslav revealed his mission at last by opening a handkerchief laden with gold trinkets. He explained with glee that he made a living by running gold into France. We became very uneasy, having had enough problems lately without being involved with bullion smuggling, but decided to continue with the fellow, hoping that he would manage to keep out of trouble.

Our transport from Turin to Paris, the Fiat 2500cc Ghia Coupe driven by a Yugoslav gold smuggler. 13 July 1970.

Once in France he said he needed a rest and asked if I wanted to drive. I agreed and, while he slept, took the lively car onto the Autoroute and opened her up to see how she would go. When the speedometer was reading 160kph (which is about 100mph) I lost my nerve and slowed down again, but my right foot had not been right down on the floor, even then. Some 30 miles short of Paris, with the Yugoslav back at the wheel, we pulled into a service station where he told us we would have to get out, as he had changed his mind and was now not going to Paris after all. We were amazed at this sudden variation in the plan but did as we were told and waved him farewell as he turned round and headed south again - altogether a most mysterious episode.

Another lift brought us into Paris, where we made for the Place de la Republique, as it was here that my former employer, Skyways, had their town terminal for the London-Paris air ferry. I managed to scrounge a couple of seats on the next bus heading north to Beauvais airport and, encouraged by this success, approached the airport staff with a view to getting a lift on the next plane to England. It transpired that the last flight of the day would be returning empty at 8pm and we were told that the captain of the aircraft would have to decide whether or not we could travel.

When the aircraft landed I was delighted to discover that the Captain was an old friend - an amiable, diminutive, bearded Czech known to all in the airline as Tarko (his real name was unpronounceable by Brits) and he readily agreed to take us. Lyn spent the whole journey up on the flight deck chatting to the dashing First Officer, while I tried to snatch a little sleep down the back. By 9 o'clock we had landed at the small airport of Lympne, near Folkestone, and thanked our hosts by buying them drinks at the local pub. Then came the worst part of the journey, a cold and liftless night trying to hitch along the coast road to Eastbourne. We finally arrived at my parents' house in time for breakfast and then both fell asleep. Although we had travelled from Latisana to Folkestone in only 31 hours (an average of 35 miles an hour) that average was reduced to 27 mph by the final dismal English section. Still it was a pretty good pace for hitch-hiking. Later Lyn set off once more to her home in Hammersmith and I never saw her again.

The next couple of days was spent begging and scrounging funds, and encouraging all our friends to come down to Latisana for a few days - I felt this would help to raise John's spirits. His parents were naturally concerned to learn of his plight, but I did my best to reassure them, not an easy matter since I wasn't entirely reassured myself.

After four days in Eastbourne I left to return to Latisana, and found that it was not as easy hitch- hiking on my own as it had been with the aid of Lyn's legs. I went by train from Eastbourne to Folkestone (actually it took three trains to achieve that, and probably still does), ferry to Boulogne and then hitch-hiked through the night into Central France, on to Grenoble and up into the Alps. Unfortunately I chose a quiet route across into Italy and finally ground to a halt near a tiny mountain frontier late on the second night. I had to give up and took a small room in a local pension to catch up on lost sleep.

I awoke early and had a hearty breakfast before setting off again. By 11 o'clock that night I was a mere 20 kilometres inside Italy - a disastrous day. Just as I was about to give up again, a smart Mercedes stopped and I was whisked into Turin. Several trucks carried me through the night on to Milan and via the Autostrada to Venice by mid-morning. No more lifts were forthcoming so I started walking to keep myself awake. Finally, at three in the afternoon, I saw a bus going to Latisana and jumped on board. (Later I worked out that my rate of progress on the journey had been a pitiful average of 16 mph.) John was pleased to see me and I was encouraged to see that he was progressing well, though he said he had had a nasty moment when he looked in the mirror for the first time. He needn't have worried on that score - time would prove that his face wounds healed perfectly. Our diary records that I "slept well" that night.

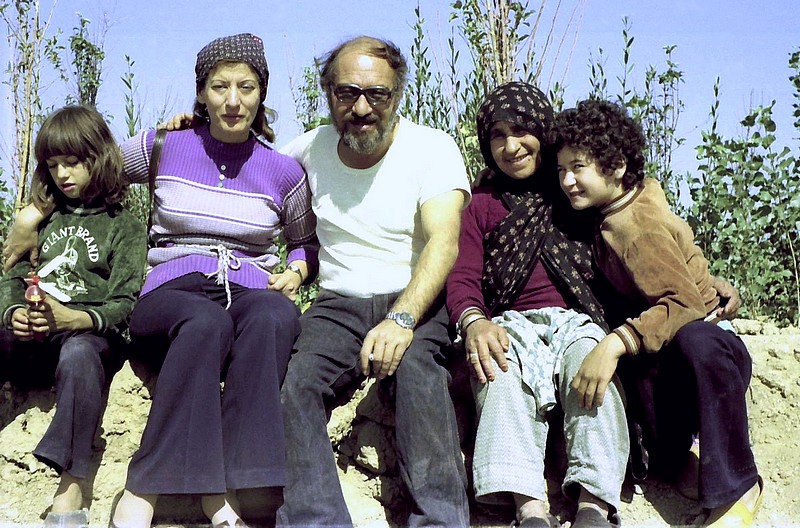

While I had been away, some remarkable things had occurred. Apparently the news of our accident had soon spread around the little town and several local parents had got together and decided that John needed cheering up, so they had instructed their teenage offspring to visit him in hospital regularly. Every day someone had been to see him in ward 5, floor 1, and brought him fruit, flowers, orange drinks and even copies of the Daily Mirror (where did they get those from?). Some spoke English, some didn't, but they still came. The mainstays of this group were four girls and a boy; first there was Marie-Louise (known to her friends as Lula) who lived at the end of our street and spoke good English. She was seventeen, had a strict father, a garden full of pets, an ill-treated moped and strong political views. Then there was Bruna, known to her friends as Bruny - she was fifteen, very tall and elegant with long legs and beautiful dark hair. John fell in love again, for a while. Louisa was 16, spoke impeccable French, liked maxi-skirts and seemed quite intellectual. Livia was 15, but looked and behaved as though she was 20. Finally there was Danielli, who fancied himself as quite a local Casanova, played guitar a little and spoke incessantly in several languages. These five, sometimes accompanied by others, became great friends of ours and were a major aid to John's recovery.

Marie-Louise, leader of John's teenage recovery team. Latisana.

So with John improving steadily it was now a game of patience for me, and I spent each day either working on the van or sitting at the hospital with the patient. Dougal had survived the fire unscathed apart from some blistered paint, so I was able to continue with the engine installation where John had left off. He gave me repair instructions from his bedside, and I would drag myself off through the baking hot backstreets to carry them out. Then I would drag myself back again to let him know how things were going. The heat was staggering - much worse than anything we had experienced further east.

The staff at the garage were really helpful, showing interest and genuine concern regarding developments at the hospital; indeed some of them visited John from time to time. There were perhaps a dozen of them and none spoke any English, but this didn't prevent them from making it clear they were happy to assist in any way. For instance, they charged Dougal's batteries so that I could have lighting in the van at night.

Bruny, another member of John's supporters' club. She couldn't understand a word we said. 19 August 1970.

Several long, weary days passed and then, one evening when I was sitting alone in the van desperately trying to think of something to write in our diary, I heard the unmistakable sound of a souped-up Mini being driven by a maniac. There was a squeal of brakes outside and I was greeted by three of our friends from Eastbourne. Dave Calderwood, the driver of the Mini and my old schoolmate Martin Giddey (they were the pair who had sent the music tape to Tehran) had decided to make their journey east as they had planned, though they now knew that our situation had changed. Their new plan was to spend a few days with us in Italy before heading off to Istanbul. Dave's brother Andrew Calderwood had also come along for the ride and had a vague idea that he might hitch-hike to Oslo, after a day or so in Latisana.

It was wonderful to see them, and we sat up half the night catching up with news and discussing their onward journey. In the morning we all went to see John, who was delighted, and general morale took a huge boost. Later, the four of us who were mobile went to Lignano Sabbiadoro and got pleasantly wet. Lo and behold, the next day another Dave (Dave Bradley) and his friend Geoff (who worked in an Eastbourne music shop) arrived, having had a pretty rough time hitch-hiking. Car loads of people now commuted between the van, the hospital and Lignano while John began to forget about his troubles. Morale kept rising. The following day Geoff and Andrew hitched off to Oslo, which left five of us - Dave and Martin, the other Dave, John and myself. Marie- Louise invited us all round to her house in the evening and plied us with wine while we played Led Zeppelin music and her mother washed my clothes.

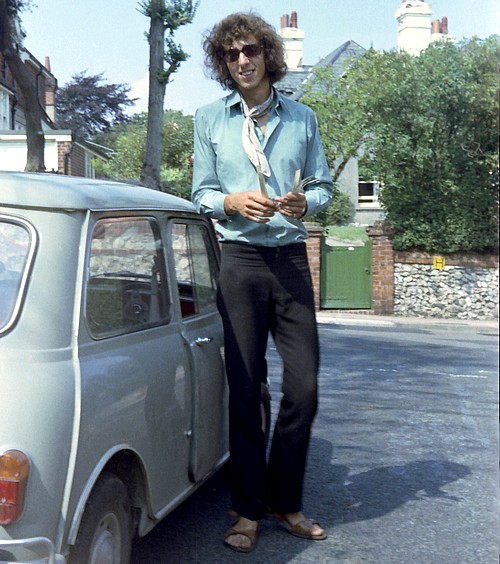

Dave Calderwood and his grey Mini, back in Eastbourne. You wouldn't think he'd fit in there, would you?

Marie-Louise took rather a liking to the second Dave and was a little upset when, after a couple of days, he left us to return to England, and then we were four. We continued to visit John two or three times a day, ignoring official visiting hours. Some nights we were still at the hospital after 10 pm and no-one ever seemed to mind. During the day we would make short visits to the sea in an attempt to keep cool. Each day Martin, a student nurse who had just taken his qualifying exams, checked the Latisana Post Office for a letter from his father confirming the results. Finally the letter arrived - he had passed - and, after appropriate celebrations, it was time for the pair to leave us and continue their journey to Istanbul. Although a part of me longed to go with them, we felt so dishevelled, disorganized and broke that the over-riding desire was to get home and recover. Even so, I couldn't avoid a pang of regret as the grey Mini roared away eastwards.

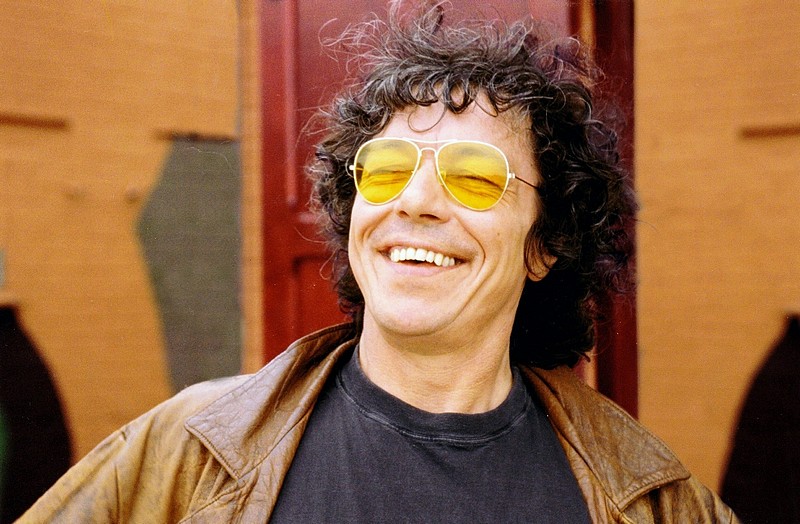

As the days went by, John's condition and demeanour improved and the doctors began to talk about releasing him in perhaps a couple of weeks. The burns were healing gradually, his face had turned from burnt brown to mottled pink, his wayward hair was spreading again, and only his left foot remained as a cause for concern. So by the time our next visitors - Terry Keating and Ann - arrived he was a very different spectacle from the shattered character that had been admitted to the hospital a month before. Terry was a calm, rather vague, friendly and harmless fellow who kept our spirits up admirably with his dry and sometimes unfathomable ramblings. He spent hours and hours, day and night, playing my guitar. Some years earlier I had taught him a few simple chords and, by incessant practice, he became a veritable virtuoso, later progressing to twelve-stringed instruments, slide, Hawaiian and pedal-steel guitars. He left me in the dust. Later he made a successful career out of writing music for TV.

Terry Keating practising endlessly on my guitar. Latisana, 6 August 1970.

Ann had accompanied him in the hope of developing their relationship, but the plot failed because Terry lived on another plain and seemed to have little need of such worldly sustenance. As a result Ann chose to occupy her mind with mundane domestic duties around the van, in which respect she was effective and uncomplaining. Later she became mildly enamoured with Danielli, our tame local youth, which softened the blow somewhat.

It was about this time that Mario came into our lives with a bang - he rode his bicycle into Dougal's already battered side doors. It was around 10 o'clock at night and he was obviously drunk. As we stepped outside to investigate the commotion he started another one in the form of a furious argument with a passing resident which nearly culminated in fisticuffs. We later discovered that Mario had been accused of stealing plums from a front garden, a habit for which he was well known in the area when returning from his riotous evening drinking sessions. This particular confrontation fortunately ended in stalemate, as the prosecution was without evidence and therefore found pursuit of the matter fruitless.

Mario was a middle-aged extrovert whose major preoccupation seemed to be the limitless consumption of local wines. He had a straight-man, Orlando, who also rode an ancient bicycle and had the unenviable and thankless function of keeping Mario out of trouble. The unsteady pair accosted us nightly after this, bringing us fruit and wine, the origins of which were doubtful, and seeing us as an excuse to continue their revelry after the bars had thrown them out. Although they were full of goodwill and hilarity, with basic Italian language lessons thrown in, we found them a terrible strain after a while, especially in the early hours when we were trying to sleep.

August 5th being John's birthday, we smuggled some wine into the hospital for him - not a difficult matter since wine was served regularly with meals there anyway. His parents had also given me some goodies for the occasion. Other than this mild diversion, the routines, the boredom and the heatwave ground on unabated until, on August 10th, I completed the repairs to the engine, recharged the battery and, to everyone's surprise, started it up. We felt this was an extremely good sign. Soon afterwards I risked driving the van to the coast to give our guests a chance to dip in the sea. Dougal behaved perfectly. John, meanwhile, had received a belated birthday letter from his uncle offering financial assistance. He jumped at the chance and made arrangements for a transfer to the British Embassy in Trieste, about 50 miles away. Here was another good omen and morale rose again.

The greatest boost, however, came next morning when John was released from hospital after 38 days. He walked unaided from the hospital to the van, arriving just as we were getting up. Various parts of his anatomy were bandaged and he walked with a stick. His left foot was wrapped up so thoroughly that it was too large for his boots, so he wore one boot and one slipper (how fortunate it was that he had remembered to pack his slippers). We spent the day following him around as he visited all the people who had supported him over the previous few weeks. He was the hero of the day, and a street party in his honour was held beside the van that evening. Marie-Louise played guitar and sang enthusiastically - though not very accurately - while Mario and Orlando drank themselves insensible.

During the following day I began to get indications of a stomach complaint which, within 24 hours, turned into something quite nasty with a fever thrown in. At four o'clock in the afternoon I was admitted to hospital and confusion reigned supreme. The doctors launched me into an intensive series of antibiotic injections which were decidedly painful. I chose to have them all in the same patch of well-padded flesh which, although seriously bruising the target area, did at least give me one side to lie and sleep on. While I spent two penicillin-punctuated days in confinement, the cash arrived in Trieste so Terry and Ann hitched off to collect it. They returned from Trieste and I returned from the hospital simultaneously, so we were at last in a position to head for home.

Then followed one last party, at which all the familiar faces were to be seen. Danielli made amorous farewells to Ann, who subsequently became tearful. Mario bade us godspeed dozens of times and rounded off his evening with another brush with bloodshed, this time in connection with some vanishing tomatoes. Bruny attended briefly which put the sparkle back into John's eyes, and another young friend, Claudio, brought out four steaming hot pizza pies he had made for us, then excelled himself by producing several bottles of superb wine from his father's cellar. It was an unforgettable evening but with a touch of sadness as we saw the last of our remarkable supporters' club. Marie-Louise became very emotional and sang all her familiar songs flat, instead of sharp. We would miss her more than anyone; she had been so faithful throughout the whole episode.

The VW garage team pose to bid us all farewell. 19 August 1970.

The haze cleared to reveal Dougal chugging out of Latisana soon after breakfast, a mere 56 hours and 1,000 miles from home. All of us looked and felt pretty rough and were looking forward to a hot bath, home cooking and English beer. We drove steadily across Italy, perhaps a little nervous about the engine. John and I took turns at the wheel and, apart from the pre-existing deterioration of the whole machine, no serious mechanical problems hindered our progress. We pressed on into the darkness, maintaining a gentle cruising speed of only about 40 mph while running-in our new components. The frontier into France was negotiated at 1 am and we got along the coast as far as Cannes before we ran out of petrol and French money, so we were obliged to pack up for the night and get some sleep.

In the morning we found a bank, changed some money, filled the tank and set off northwards on the Autoroute. Encouraged by the previous day's progress we increased the cruising speed to 45 mph, but it still made for slow progress, not least because we picked up another hitch-hiker, Jacques, who was heading for Lille. He was a decent chap, so we made a little diversion and delivered him to his intended destination.

Lille, 20 August 1970. Ann, Terry, John and myself all pretty worn out. But at least I'm still wearing a tie (and sandals and socks).

One more day and night on the road (during which we deposited Jacques) found us boarding the ferry at Calais bound for Dover and our last homeward stretch. Finally we rolled into Eastbourne and the journey was complete, despite the evil Tiki.

A Ford Capri towing a powerboat accompanies Dougal on the Calais-Dover ferry, 21 August 1970.

Dougal covered 15,000 miles during the journey and, in order to repay money we had been loaned, we reluctantly put him up for sale at Eastbourne Car Auctions. He made £35 which represented an overall loss of only £5. That was pretty remarkable considering what he had been through. In retrospect he was too old, underpowered, overloaded and had bad lights. There was no need for our elaborate crash bars as it happened, but the padlocks were effective - we had nothing stolen during the entire journey.

We didn't take enough care of Dougal en route and we didn't manage our finances as well as we might have done - in fact we didn't take enough cash in the first place, but then you probably never do. It might have been more enlightening to have returned via a different route - for instance incorporating southern Turkey, or crossing Europe through Austria and Germany - but there were equally good reasons for not doing so, such as our shortage of cash and a well-founded fear that Dougal would never be able to negotiate the Alps with half an engine and poor brakes.

A last look at a battered Dougal, back in Eastbourne, before he was sold.